From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

SF Judge Dismisses Charges Against BART's Powell Street Station Free Speech Arrestees, 6/4/12

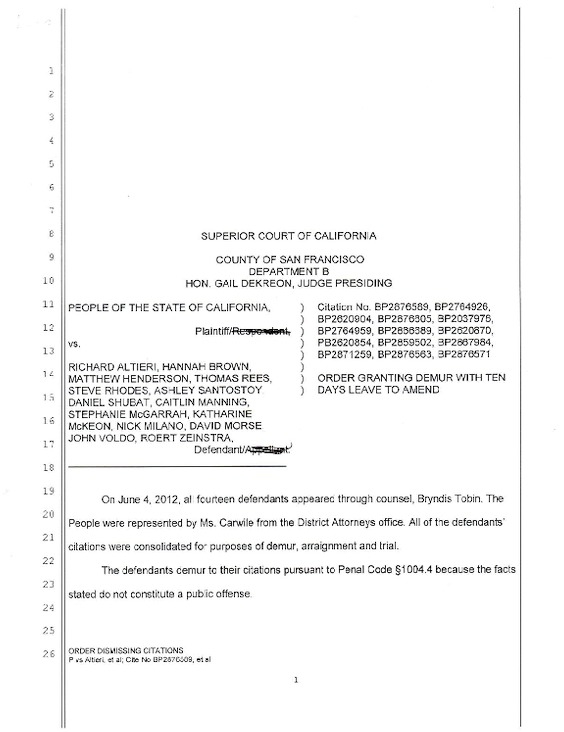

On September 8th, 2011, BART police wrongfully mass arrested close to thirty people, including this reporter, inside the Powell Street BART station during a protest against BART police. Protesters and journalists alike were handcuffed for hours and charged with violating California Penal Code Section 369i, which forbids that anyone "interfere with, interrupt, or hinder the safe and efficient operation of any locomotive, railway car, or trains," even though those arrested were doing no such thing. Nearly nine months later, on June 4th, the case was finally heard in open court. Thanks to the strength of the demurrer, or motion for dismissal, made by Bryndis Tobin of the National Lawyers Guild, the District Attorney's office submitted to the demurrer and didn't contest any of the defense arguments. The DA's office further indicated that they had no intention of filing amended charges, ever. And so it was not surprising when San Francisco County Superior Court Judge Gail Dekreon thereby dismissed charges against all of the defendants whom the NLG represented in the case.

[Pictured above: BART police deputy chief Dan Hartwig can be seen behind a "Disband BART Cops" banner. Photo by D. Boyer.]

It was especially not surprising that BART's bogus charges were dismissed outright by Judge Dekreon, the presiding judge of the San Francisco Traffic Division, because the judge already had an order granting the demurrer with ten days leave to amend, on the grounds that the facts stated did not constitute a public offense, in that Penal Code 369i is a misdemeanor but the defendants were cited with an infraction violation, something that does not even exist. With the DA's office declining to seize the opportunity to file amended charges, BARTs case was finished.

While the infraction/misdemeanor/public offense issue might appear to be letting defendants off on a technicality, it was simply the most glaring problem with the charges BART had made. Also in the demurrer, more significantly, it is noted that Penal Code 369i(c) states: "This section does not prohibit picketing in the immediately adjacent area of the property of any railroad or transit-related property or any lawful activity by which the public is informed of the existence of an alleged labor dispute." In effect, BART charged arrestees, protesters and journalists, with a statute that specifically protects first amendment activities.

From the demurrer:

Nine months late, this dismissal of charges serves to put the exclamation point on the well-known fact that BART police once again stepped over the line, overreacting to a protest against its own police force's brutality. Nevertheless, though, for BART, the mass arrest already served its purpose, regardless of the legal outcome. Rather than tolerate dissent in its midst, even in the unpaid area BART had previously said was permissible for free speech activity, BART police chose to detain upwards of 50 people, a large number of whom were journalists — ultimately arresting around 30 people, some of whom BART knew to be journalists — and close the entire Powell Street BART station to the public for over two hours. This is how much BART hates free speech. Illegal arrests such as these serve to chill free speech activity and BART damned well knows that.

But this chapter is not yet over. People can continue to stand up for their own rights and the rights of others if they so choose. California legislator Alex Padilla has gotten legislation through the state Senate which, if passed by the Assembly and signed by the governor, will ban BART from ever again shutting down mobile phone antennas without a court order. Let your Assembly member know you support SB 1160 and any equivalent bills in the California Asembly.

On a separate front, this reporter filed a complaint with BART police over my September 8th arrest which has yet to be resolved, the complaint "investigation" having been put on hold by BART Internal Affairs pending the outcome of the 369i case. Granted, police investigating themselves is a bit of the fox guarding the henhouse, and the most likely outcome would be for BART to find no wrongdoing in the actions of deputy chief Dan Hartwig for targeting a journalist known for being critical of BART police abuses. Notwithstanding the results of BART's internal investigation of itself, this reporter has also filed a state tort claim reserving my right to file a civil lawsuit against BART over the wrongful arrest.

The National Lawyers Guild only represented fourteen of the arrestees in court on June 4th, all of whom were cited and released at 850 Bryant on September 8th. Four others who were booked into the SF County jail for up to seven hours had their 369i charges dropped within two weeks of the September 8th demonstration. Unfortunately, as for the other ten or more arrestees also cited and released, it is unknown if they sought independent counsel, paid a fine for the infraction, had their charges likewise dismissed, or if their charges remain pending.

Reaching out today to BART for comment about the charges having been dismissed in court, spokesman Jim Allison said that he was unaware the case had been resolved. In a second phone call, he added that BART supports the determinations of the criminal justice system. Allison would not speculate on what this case might mean for BART's handling of future demonstrations, other than to say that BART police are receiving increased training (a common BART public relations refrain), BART police are professionals, and BART expects them to act professionally in the future. We'll see.

-------------------------

For more information about the case and related issues:

Society of Professional Journalists Committee Scolds BART for Actions at Sept. 8th Protest

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/10/07/18692542.php

No Justice No BART and Allies Call for "Spare the Fare" Protest in Powell Street BART

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/09/07/18689663.php

BART Pulls Plug on Cell Phone Antennas to Silence Potential Protest

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/08/13/18687583.php

Justice for Charles Hill BART Action Shuts Three Stations in San Francisco

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/07/19/18685301.php

Indybay Coverage of the Justice for Oscar Grant Movement

http://www.indybay.org/oscargrant

-------------------------

Bryndis Tobin of the National Lawyers Guild said big thanks were due to Bobbie Stein & Rachel Lederman, who were tremendously helpful and contributed significantly to the demurrer writing project. She also wanted to credit an excellent article she found here: http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/09/12/18690120.php. The primary author, Jay Lederman, is a movement attorney who mostly works in SoCal - see http://www.leidermandevine.com/ht_docs/press.php.

Bryndis additionally asked that a shout out be given to the SEIU and their efforts to keep our court systems funded — http://www.seiu1021.org/content/courts-industry-council — and the general movement to try and prevent further damage due to cuts — http://www.courts.ca.gov/partners/courtsbudget.htm. The clerks in traffic are really having a hard time, but they were very nice, remarkably efficient and really deserve some backing... especially since if we don't improve things for them, life is going to suck so very much more for everyone who has to have anything to do with the court system over the next few years. If you haven't seen the line for the traffic clerks these days in CA, it's shocking.

-------------------------

Donate to the NLG! If the NLG has ever gotten you out of a tight spot when police have wrongfully arrested you for expressing your first amendment rights, or if you simply want to show support for the work that they do, please make a financial contribution to the National Lawyers Guild. Help them continue their demonstrations support work, which includes a legal hotline, tracking of arrests, recruiting, training and coordinating legal observers, lawyers, and legal support workers, and advocating to stop police misconduct against demonstrators. The suggested donation is $50 - $100 for employed people; please give what you can. Checks can be payable to the NLG with "Demo Committee" in the memo line and sent to NLGSF, 558 Capp Street, SF, CA 94110; or you can use Paypal by clicking on the "donate" link on their web site at www.nlgsf.org.

-------------------------

The Demurrer:

It was especially not surprising that BART's bogus charges were dismissed outright by Judge Dekreon, the presiding judge of the San Francisco Traffic Division, because the judge already had an order granting the demurrer with ten days leave to amend, on the grounds that the facts stated did not constitute a public offense, in that Penal Code 369i is a misdemeanor but the defendants were cited with an infraction violation, something that does not even exist. With the DA's office declining to seize the opportunity to file amended charges, BARTs case was finished.

While the infraction/misdemeanor/public offense issue might appear to be letting defendants off on a technicality, it was simply the most glaring problem with the charges BART had made. Also in the demurrer, more significantly, it is noted that Penal Code 369i(c) states: "This section does not prohibit picketing in the immediately adjacent area of the property of any railroad or transit-related property or any lawful activity by which the public is informed of the existence of an alleged labor dispute." In effect, BART charged arrestees, protesters and journalists, with a statute that specifically protects first amendment activities.

From the demurrer:

Not only do these citations fail to state a public offense, but the very statute they are alleged to have violated specifies that their actions cannot be prohibited under that statute, whether the defendants were demonstrating or, as is the case with some defendants, covering the demonstration in their capacity as journalists. To survive Constitutional scrutiny, Pen. Code 369i (c) cannot be read to protect only speech regarding labor disputes; content based restrictions on speech are valid only when "narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest." …If a labor dispute can lawfully be picketed under the statute, certainly a protest involving railroad related activities, such as the brutality of BART police, is covered both by the First Amendment and the penumbra of speech in 369i(c).Judge Dekreon written decision on the case is still pending. It remains to be seen whether the judgement will rely solely on the infraction misclassification or will go further by highlighting Section(c) of PC 369i or any of the other legal problems enumerated in the demurrer.

Nine months late, this dismissal of charges serves to put the exclamation point on the well-known fact that BART police once again stepped over the line, overreacting to a protest against its own police force's brutality. Nevertheless, though, for BART, the mass arrest already served its purpose, regardless of the legal outcome. Rather than tolerate dissent in its midst, even in the unpaid area BART had previously said was permissible for free speech activity, BART police chose to detain upwards of 50 people, a large number of whom were journalists — ultimately arresting around 30 people, some of whom BART knew to be journalists — and close the entire Powell Street BART station to the public for over two hours. This is how much BART hates free speech. Illegal arrests such as these serve to chill free speech activity and BART damned well knows that.

But this chapter is not yet over. People can continue to stand up for their own rights and the rights of others if they so choose. California legislator Alex Padilla has gotten legislation through the state Senate which, if passed by the Assembly and signed by the governor, will ban BART from ever again shutting down mobile phone antennas without a court order. Let your Assembly member know you support SB 1160 and any equivalent bills in the California Asembly.

On a separate front, this reporter filed a complaint with BART police over my September 8th arrest which has yet to be resolved, the complaint "investigation" having been put on hold by BART Internal Affairs pending the outcome of the 369i case. Granted, police investigating themselves is a bit of the fox guarding the henhouse, and the most likely outcome would be for BART to find no wrongdoing in the actions of deputy chief Dan Hartwig for targeting a journalist known for being critical of BART police abuses. Notwithstanding the results of BART's internal investigation of itself, this reporter has also filed a state tort claim reserving my right to file a civil lawsuit against BART over the wrongful arrest.

The National Lawyers Guild only represented fourteen of the arrestees in court on June 4th, all of whom were cited and released at 850 Bryant on September 8th. Four others who were booked into the SF County jail for up to seven hours had their 369i charges dropped within two weeks of the September 8th demonstration. Unfortunately, as for the other ten or more arrestees also cited and released, it is unknown if they sought independent counsel, paid a fine for the infraction, had their charges likewise dismissed, or if their charges remain pending.

Reaching out today to BART for comment about the charges having been dismissed in court, spokesman Jim Allison said that he was unaware the case had been resolved. In a second phone call, he added that BART supports the determinations of the criminal justice system. Allison would not speculate on what this case might mean for BART's handling of future demonstrations, other than to say that BART police are receiving increased training (a common BART public relations refrain), BART police are professionals, and BART expects them to act professionally in the future. We'll see.

-------------------------

For more information about the case and related issues:

Society of Professional Journalists Committee Scolds BART for Actions at Sept. 8th Protest

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/10/07/18692542.php

No Justice No BART and Allies Call for "Spare the Fare" Protest in Powell Street BART

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/09/07/18689663.php

BART Pulls Plug on Cell Phone Antennas to Silence Potential Protest

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/08/13/18687583.php

Justice for Charles Hill BART Action Shuts Three Stations in San Francisco

http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/07/19/18685301.php

Indybay Coverage of the Justice for Oscar Grant Movement

http://www.indybay.org/oscargrant

-------------------------

Bryndis Tobin of the National Lawyers Guild said big thanks were due to Bobbie Stein & Rachel Lederman, who were tremendously helpful and contributed significantly to the demurrer writing project. She also wanted to credit an excellent article she found here: http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2011/09/12/18690120.php. The primary author, Jay Lederman, is a movement attorney who mostly works in SoCal - see http://www.leidermandevine.com/ht_docs/press.php.

Bryndis additionally asked that a shout out be given to the SEIU and their efforts to keep our court systems funded — http://www.seiu1021.org/content/courts-industry-council — and the general movement to try and prevent further damage due to cuts — http://www.courts.ca.gov/partners/courtsbudget.htm. The clerks in traffic are really having a hard time, but they were very nice, remarkably efficient and really deserve some backing... especially since if we don't improve things for them, life is going to suck so very much more for everyone who has to have anything to do with the court system over the next few years. If you haven't seen the line for the traffic clerks these days in CA, it's shocking.

-------------------------

Donate to the NLG! If the NLG has ever gotten you out of a tight spot when police have wrongfully arrested you for expressing your first amendment rights, or if you simply want to show support for the work that they do, please make a financial contribution to the National Lawyers Guild. Help them continue their demonstrations support work, which includes a legal hotline, tracking of arrests, recruiting, training and coordinating legal observers, lawyers, and legal support workers, and advocating to stop police misconduct against demonstrators. The suggested donation is $50 - $100 for employed people; please give what you can. Checks can be payable to the NLG with "Demo Committee" in the memo line and sent to NLGSF, 558 Capp Street, SF, CA 94110; or you can use Paypal by clicking on the "donate" link on their web site at www.nlgsf.org.

-------------------------

The Demurrer:

III. THE CITATION FAILS TO STATE A PUBLIC OFFENSE A. The Offense As Charged Does Not Exist Pen. Code section 1004(4) dictates that a defendant may demur to the accusatory pleading “when it appears on the face thereof” that the facts stated do not constitute a public offense. The accusatory pleading in this case states that the only charge against defendants is that they committed a public offense which does not exist. Pen. Code section 369i specifies that anyone who commits the acts described in subsections (a) or (b) “is guilty of a misdemeanor.” Nowhere within Pen. Code section 369i is there language that creates a public offense that may be charged as an infraction. However, according to the charging documents in this case, the citations received by defendants, they are being accused of an infraction. Some of the citations have the word “Infraction” handwritten at the top of the face, or front, of the citation in addition to the officer having circled an “I” rather than an “M” where the form is designed to indicate whether the offense is a misdemeanor or an infraction. Quite literally, it appears on the face of the accusatory pleading that the facts stated do not constitute a public offense. For this reason, the demurrer must be sustained. B. Penal Code Section 369i(c) Specifically States That Defendants’ Conduct May Not Be Prosecuted Under This Section. The charging documents in this case do not specify which subsection of Pen. Code section 369i applies to defendants. However, there is a subsection that does apply to this case. Pen. Code section 369i(c) states: (c) This section does not prohibit picketing in the immediately adjacent area of the property of any railroad or transit-related property or any lawful activity by which the public is informed of the existence of an alleged labor dispute. “Had petitioners in any way interfered with the conduct of the railroad business, they could legitimately have been asked to leave.” (In re Hoffman, 67 Cal. 2d 845, 852 (1967).) Absent any specific allegations regarding what, where and how defendants violated Pen. Code 369i, however, all that remains is an allegation that defendants were in or near the Powell Street BART station. Penal Code section 950 states that the accusatory pleading must contain a statement of the public offense or offenses charged. Penal Code section 952 provides that "in charging an offense, each count shall contain, and shall be sufficient if it contains in substance, a statement that the accused has committed some public offense therein specified" [emphasis added]. Not only do these citations fail to state a public offense, but the very statute they are alleged to have violated specifies that their actions cannot be prohibited under that statute, whether the defendants were demonstrating or, as is the case with some defendants, covering the demonstration in their capacity as journalists. To survive Constitutional scrutiny, Pen. Code 369i (c) cannot be read to protect only speech regarding labor disputes; content based restrictions on speech are valid only when "narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest." (See, e.g., Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, 494 U.S. 652, 655 (1990); Boos v. Barry, 485 U.S. 312, 334 (1988) (plurality); see also Burson v. Freeman, 504 U.S. 191, 198 (1992) (plurality); Board of Airport Comm'rs v. Jews for Jesus, Inc., 482 U.S. 569, 573 (1987); Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Defense and Educ. Fund, Inc., 473 U.S. 788, 800 (1985); United States v. Grace, 461 U.S. 171, 177 (1983); Perry Educ. Ass'n v. Perry Local Educators' Ass'n, 460 U.S. 37, 45 (1983).) If a labor dispute can lawfully be picketed under the statute, certainly a protest involving railroad related activities, such as the brutality of BART police, is covered both by the First Amendment and the penumbra of speech in 369i(c). The California Supreme Court confronted this question in the context of anti-war leafleting in the case of In re Hoffman, 67 Cal. 2d 845 (1967). On September 5th, 1966, about 15 protesters entered the then privately- owned Union Station in Los Angeles to distribute leaflets opposing the Vietnam War. Although they stayed in the main entrance and lobby, several of the protesters were arrested and convicted under a municipal ordinance prohibiting anyone from remaining in a rail station “for a period of time longer than reasonably necessary” to conduct business with a carrier. Addressing a constitutional challenge to the ordinance, the Hoffman Court explained that the First Amendment allows for “reasonable time, place and manner restrictions.” Narrowly tailored laws may prevent people from congesting “areas where their presence would threaten personal danger or block the flow of passenger or carrier traffic,” such as loading areas, doorways, ticket windows and turnstiles. (Hoffman, 67 Cal. 2d at 853.) But the ordinance at issue “completely prohibit[ed] protected activities although a narrower measure would fully achieve the intended ends and at the same time preserve an effective place for the dissemination of ideas.” (Id. ) Consequently, the Court struck down that section of the ordinance and overturned the convictions. "The constitutional right of free expression is powerful medicine in a society as diverse and populous as ours." (Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 24.) "[I]t is only through free debate and free exchange of ideas that government remains responsive to the will of the people and peaceful change is effected. The right to speak freely and to promote diversity of ideas and programs is therefore one of the chief distinctions that sets us apart from totalitarian regimes." (Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949) 337 U.S. 1, 4.) Nor can BART claim a private interest in restricting speech on its property. Not only is BART a public entity but, in California, even private parties that open their facilities to the general public may not abridge the free speech rights of people on their property. Indeed, “the public interest in peaceful speech outweighs the desire of property owners for control over their property.” (Robins v. Pruneyard Shopping Ctr., 23 Cal. 3d 899, 909 (Cal. 1979), aff’d 477 U.S. 74 (1980).) This is so because California's constitution contains an affirmative right of free speech, one which has been liberally construed by the Supreme Court of California. (Pruneyard, 477 U.S. 74 (1980).) The California Constitution states in Article 1, § 2 “ Every person may freely speak, write and publish his or her sentiments on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of this right. A law may not restrain or abridge liberty of speech or press. ” Article 1, § 3 states that the “ [P]eople have the right to . . . petition government for redress of grievances.” Because the citations fail to state a public offense and therefore do not comply with the requirements of Penal Code sections 950 and 952, this court should sustain Defendants’ demurrer. IV. THE CITATION FAILS TO PROVIDE CONSTITUTIONALLY ADEQUATE NOTICE. A. The Citations Do Not Describe Defendants’ Conduct With Enough Specificity. Penal Code section 950 states that the accusatory pleading must contain a statement of the public offense or offenses charged. Penal Code section 952 provides that "in charging an offense, each count shall contain, and shall be sufficient if it contains in substance, a statement that the accused has committed some public offense therein specified" [emphasis added]. The function of criminal pleadings in California is to give an accused adequate notice of the charges against him. Even though the particular circumstances of the charge need not be alleged, sufficient notice to satisfy due process must be given. (People v. Jackson (1978) 88 Cal.App.3d 490.) A bare literal compliance with Penal Code section 952 in the complaint, by simply alleging that the defendant has violated a statute, is insufficient to obviate a demurrer where a pleading in the words of the statute is insufficient to give constitutionally adequate notice of the offense. (People v. Jordan (1972) 19 Cal.App.3d 362.) The accusatory pleading here does not even do that. It simply states that a defendant was in or near a BART station. Moreover, a pleading that satisfies Penal Code section 952 may not necessarily satisfy constitutional due process requirements when tested by demurrer. (Lamadrid v. Municipal Court (1981) 118 Cal.App.3d 186, 790.) "Due process ...requires that an accused be advised of the charges against him in order that he may have a reasonable opportunity to prepare and present his defense and not be taken by surprise by evidence offered at his trial." (In re Hess (1955) 45 Cal.2d 171, 175.) Neither discovery nor an assumption that the accused has pertinent knowledge may be relied upon to furnish notice. In misdemeanor and infraction prosecutions, no transcript or preliminary examination or grand jury proceedings will be available to augment the allegations of the pleadings. (Lamadrid v. Municipal Court, supra, 118 Cal.App.3d 786). Furthermore, the prosecution must elect that one culpable act upon which it intends to rely on for conviction. "There is a presumption that the defendant in a criminal case is innocent. An innocent defendant could not determine what offense he was accused of committing from the information filed in this case." (People v. Clenney (1958)165 Cal.App. 2d 241, 253.) Such is the case in the matters before this Court. In the “Description” section, the citation merely states “interfere w/railroad” or “interfering with railroad operations.” The location of the violation is given as either “Powell St. BART Sta.,” an area over a city block long, wider than Market Street, and several stories in height or, alternatively, “899 Market” which is apparently the mailing address of the station. The citations do not mention any specific train, train platform, train track, any specific part of the station or even, in some instances, that defendants were in a BART station or on BART property at all. The citation fails to adequately notify the defendants as to how or where they violated section 369i. Therefore, the demurrer must be sustained under Penal Code section 1004(2). B. The Citations Do Not Describe The Charges With Enough Specificity (1) The Citations do not indicate which subsection of Pen. Code 369i defendants are charged with. Not only do these citations fail to state a public offense, but the very statute they are alleged to have Penal Code section 369i is comprised of two subsections which describe criminal conduct. Subsection (a) applies only to entry, presence or conduct that “interferes with, interrupts, or hinders, or which, if allowed to continue, would interfere with, interrupt, or hinder the safe and efficient operation of any locomotive, railway car, or train” and takes place on land immediately adjacent to a railroad track and within 20 feet of the track. Subsection (b) applies only to transit related facilities. Thus, the prosecution must designate a subsection under which it is proceeding. As currently alleged, the defendant has no way of knowing what the prosecution is intending to prove. Proper notice of a violation of this section must articulate the alleged act that was committed. In the instant case, not only has the prosecution failed to name which of the types of conduct were allegedly involved, it has not described any act at all. Here, the charging documents fail to give information that is necessary for defendants to prepare a defense since the citations do not state which subsection of Pen. Code 369i was violated, what the defendants did to violate the law or where they did it. Certainly, at minimum, the accusatory pleading must indicate whether defendants are charged with interfering with a railroad train or a railroad station. Without this, defendants are unable to prepare a defense. (2) The citations do not clearly indicate whether defendants are charged with an infraction or a misdemeanor. While Pen. Code 369i expressly classifies this offense as a misdemeanor, not an infraction, the citations defendants received either were clearly marked as infractions or left blank where the form is designed to indicate whether the alleged offense is an infraction or a misdemeanor. A BART Police Officer writing the word “Infraction” on a citation does not change the content of the California Penal Code. Neither does the fact that the District Attorney has tried to “infract” the cases by referring it to traffic court convert the charge to an infraction. (See, People v. Tracy, 22 Cal. 3d 760 at 765 (1978) [Every crime that is not a felony is a misdemeanor except those that are classified as infractions]. However, having “INFRACTION” in large block letters across the top of the charging document does seem to indicate that the defendants are charged with an infraction. Whether defendants are charged with a misdemeanor or an infraction gravely affects their rights. Pen. Code section 19.6 states: “A person charged with an infraction shall not be entitled to a trial by jury. A person charged with an infraction shall not be entitled to have the public defender orother counsel appointed at public expense to represent him or her unless he or she is arrested and not released on his or her written promise to appear, his or her own recognizance, or a deposit of bail.” Misdemeanor defendants, however, are entitled to the assistance of court-appointed counsel (Cal. Const., art. I, § 15; Pen. Code, § 686; Mills v. Municipal Court, 10 Cal. 3d 288, 301.) They are also entitled to a jury trial (Cal. Const., art. I, § 16, 24). If a court may not replace misdemeanor charges with infraction charges merely to avoid according the accused his constitutional rights (see, e.g., In re Kevin G., 40 Cal 3d 644 at 647 (1985).) certainly they may not disguise misdemeanor charges as infractions in order to avoid according the accused his constitutional rights. If defendants are indeed charged with a misdemeanor, they do not wish to waive their right to have to appointed counsel or to a jury trial. "Due process ...requires that an accused be advised of the charges against him in order that he may have a reasonable opportunity to prepare and present his defense..." (In re Hess (1955) 45 Cal.2d 171, 175.) If, as here, defendants do not know with certainty from the charging documents whether they are charged with a misdemeanor or an infraction, or if they are entitled to appointed counsel or trial by jury, they do not have a reasonable opportunity to prepare and present their defense; the requisites of due process have not been satisfied. A further reason why particularity is required is so the defendant may plead the judgment as a bar to any later prosecution for the same offense. (People v. Jordan (1971) 19 Cal.App.3d 362, 368.) Unlike in a felony case where the testimony at the preliminary hearing, combined with the information, might inform the defendant of the charges she is facing and the facts underlying these charges, there is nothing in the instant case to clarify the charges. Due process has not been satisfied here where there is insufficient specificity to bar any later prosecution for the same offense and where defendant will be taken by surprise at trial.

For more information:

http://indybay.org/oscargrant

Add Your Comments

Latest Comments

Listed below are the latest comments about this post.

These comments are submitted anonymously by website visitors.

TITLE

AUTHOR

DATE

A Victory or A Defeat?

Wed, Jun 6, 2012 12:59PM

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network