Utah Phillips has left the stage

Recently Utah wrote a letter to his friends and family and we would like to share that with you.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

A Note From Utah

Dear Friends,

Utah here, with a rambling missive pandect and organon regarding my current reality. At no time should you suspect me of complaining (kvetching); I am simply grepsing (Yiddish word for describing the condition of that reality).

First, medical: My heart, which is enlarged and very weak, can’t pump enough blood to keep my body plunging forward at its usual 100 percent. It allows me about 25 to 30 percent, which means I don’t get around very much or very easily anymore. I’m sustained (i.e., kept alive) by a medication called Milrinone, which is contained in a pump that I carry around with me in a shoulder bag. The pump, which runs 24 hours a day, moves the medication through a long tube running into an implanted Groshong catheter that in turn runs directly into my heart. I’ll be keeping this pump for the rest of my life. I also take an extraordinary number of oral medications, of which many are electrolytes.

My body is weak but my will is strong, and I keep my disposition as sunny and humorous as I’m able. It’s hard enough being disabled without being cranky as well. Though I’m eating well, my weight has gone from 175 to 155 pounds. I look like a geriatric Fred Astaire.

We manage to get out a good bit, visiting the Ananda (a local spiritual village and retreat center) flower garden up on the San Juan Ridge and occasionally going to lunch at various places around town. The bag is always with me. Believe me, none of this would be possible without my wife Joanna. She has the deepest, most loving and caring heart one could ever imagine. She’s taken charge of all my medications and makes sure that I’m well fed and don’t fall into the slovenly ways of a derelict. She also has enormous physical beauty—I have never seen a more beautiful woman in my life. She is endowed with intelligence, deep insight, compassion, and a capacity for love that passes all understanding.

Heart disease aside, I find that I have a hernia that needs to be repaired. Someday I suppose I’ll become like Ernie Bierwagen, the old man who owned the orchards outside town. He said to me once, “I know that God wants me to say something, because the only thing I have left that works is my mouth.” But for now, I’m enjoying my life and can think of no good reason not to. Joanna and I both know that the chemical regimen I’m on can’t go on indefinitely. We take things a day at a time, deriving joy and solace from a solid, loving relationship.

I want to share with you something about where we live. If you’re reading this on the Internet, I’ve sent Duncan some photos to show you what it looks like. Our house is on a country lane right off Red Dog Road, about a mile from downtown Nevada City. Nevada City is an old gold-mining town in the Sierra foothills with a population of about 2,800. The old buildings are all still here, including the National Hotel, one of the oldest hotels in the West that’s still doing business. The town is a quirky, mystical sort of place, populated by poets, writers, artists, misfits, and just regular folks. When you drive down Berggren Lane where we live, you come to a brown house with green trim, lap-strake siding, a steel roof, and a high green fence around the front. The steel roof is there because we live in an ancient oak and cedar grove, which includes in the front yard a couple of towering poplar trees. Sometimes the wind coming down from the high Sierra breaks off tree limbs, and if it weren’t for the steel roof, we could well be eating our salad by the roots.

When we first moved in here, the house was tiny. Using her remarkable ingenuity and the prodigious skills of our friend Steven Goodfield, a fine independent carpenter, Joanna has added a hallway and two rooms going up the hill, which gives us a bedroom and bathroom, and me a study. The French doors in our bedroom open out onto a dappled hillside with hawthorns, cedars, pines, wild cherries, and oaks. The lot itself is quite narrow, the result of a bad survey many years ago. The old part of the house was built in 1912. When we bought it, there was a greenhouse along the southern wall. It was rotting out, so we replaced it with a new, insulated and thermo paned greenhouse so that we could remove the interior wall and make it almost part of the living room. Our house is a beautiful, comfortable place to live, absolutely surrounded by greenery.

Looking out the greenhouse windows now, I can see the huge poplars in front, already in full leaf. The front yard is Joanna’s flower garden, a great splash of color amid the green. As I look over my shoulder out the greenhouse door, which is also the front door to the house, I can see the hawthorn trees covered with cascades of white blossoms, as though their limbs were burdened with new snow. There’s a brick patio just outside the greenhouse with a fireplace and a small pond crowned with a bronze frog who emits a stream of water into the pond, which, when the weather is warm, we can hear from the bedroom when we’re going to sleep.

Opposite the greenhouse is the kitchen, with a wonderful early 1930s gas range, one of those with a two-lid firebox on one end. Outside the kitchen window is a railed porch built by our friend Kuddie, which overlooks another flower garden and an old apple tree, still bearing, that was probably planted when the house was built. The lot itself, narrow though it is, goes up the hill quite a way, where it levels off through the cedars and ends at a large open space that was a vegetable garden when I was still able to do that sort of thing.

The cedars are gigantic and quite an anomaly, a patch of forest that was never logged, probably because of the bad survey. It simply got missed. Walking in it now is like walking in the quiet of a much larger forest.

Walking up the hill, you pass three small outbuildings. One, called Marmlebog Hall (Joanna’s children call her Marmle), is where Kuddie ordered and maintained the CDs I used to travel with. It also contains a small labor library. The second building is a small barn on uneven stilts because of the hill. It’s there for storage. Don’t ask me what all is in it, but I do know it would drive an archaeologist mad. Among other things, it houses about 15 collapsing cardboard boxes that contain what academics have characterized as my personal archives, but are in fact a jumble of papers and objects, the detritus of over half a century. The University of California at Davis once said they wanted to accession my archives. I said, okay, if you hire somebody to come and plough through those boxes, because I’m not going to. They never called back.

The third building up there is an old shed, tiny, drafty, but a place where I spent many happy hours making things when I wasn’t traveling: wooden swords, bird feeders, and such. For the past few years the workshop has been a henhouse with a chicken-wire enclosure. Nothing fancy: five hens and a large rooster named Ralph (Rooster-Dooster). Ralph enjoys the good life. You could poke three holes in Ralph and go bowling with him. The hens all have names, but I forget what they are. They give us eggs, which I think was the idea to begin with.

Last winter a bear broke into the chicken yard and tore the door off the henhouse. The hens and Ralph managed to escape by hiding behind an old chest of drawers. The first hen to reappear showed up in our dog Bo’s mouth; she was uninjured, but that condition would not have lasted much longer. The others came out of hiding one at a time. Before our friend Che Greenwood could come over to fix the door, we feared the bear would return, plus a great storm was kicking up. So we set up a round of chicken wire in the greenhouse, which, as I say, is part of the living room, and installed the chickens there. Eventually, the smell was overpowering. How can chickens live with themselves? It was Friday evening and I’d turned on my small portable radio, as at this time the power was out, to listen to a station in Sacramento that broadcasts opera from 8:00 p.m. till midnight. That Friday one of the opera excerpts featured was an aria from Puccini’s Tosca sung by Maria Callas. That’s when Ralph decided he liked opera. As she sang, he began to crow along, so I got Tosca as a duet between Callas and Ralph. That’s when I said, these chickens have got to go back up the hill. I mean, it was Puccini, for God’s sake.

So. That’s domestic life here at our place.

A few words about me and the trade before I wind this up. When I hit a blacklist in Utah in 1969, I realized I had to leave Utah if I was going to make a living at all. I didn’t know anything abut this enormous folk music family spread out all over North America. All I had was an old VW bus, my guitar, $75, and a head full of songs, old- and new-made. Fortunately, at the behest of my old friend Rosalie Sorrels, I landed at Caffe Lena in Saratoga Springs, New York. That seemed to be ground zero for folk music at the time. Lena Spencer, as she did with so many, took me in and taught me the ropes. It took me a solid two years to realize I was no longer an unemployed organizer, but a traveling folk singer and storyteller—which, in Utah at the time, would probably have been regarded as a criminal activity.

I spent a long time finding my way—couches, floors, big towns, small towns, marginal pay (folk wages). But I found that people seemed to like what I was doing. The folk music family took me in, carried me along, and taught me the value of song far beyond making a living. It taught me that I don’t need wealth, I don’t need power, and I don’t need fame. What I need is friends, and that’s what I found—everywhere—and not just among those on the stage, but among those in front of the stage as well.

Now I can no longer travel and perform; overnight our income vanished. But all of those I had sung for, sung with, or boarded with, hearing about my condition, stepped in and rescued us. I can’t tell you how grateful I am to be part of this great caring community that, for the most part, functions close to the ground at a sub-media level, a community that has always cared for its own. We will be forever grateful for your help during this hard time.

The future? I don’t know. But I have songs in a folder I’ve never paid attention to, and songs inside me waiting for me to bring them out. Through all of it, up and down, it’s the song. It’s always been the song.

Love and solidarity,

Utah

Listen to Utah explain his condition in his own voice via podcast

For an update on his condition from his son, Duncan, and to leave a good well wish or comment, click here to visit utahphillips.blogspot.com

May 24, 2008

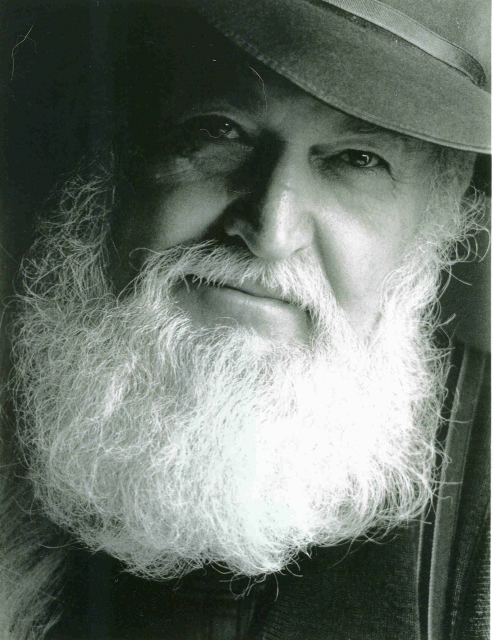

"Folksinger, Storyteller, Railroad Tramp Utah Phillips Dead at 73"

Nevada City, California:

Utah Phillips, a seminal figure in American folk music who performed extensively and tirelessly for audiences on two continents for 38 years, died Friday of congestive heart failure in Nevada City, California a small town in the Sierra Nevada mountains where he lived for the last 21 years with his wife, Joanna Robinson, a freelance editor.

Born Bruce Duncan Phillips on May 15, 1935 in Cleveland, Ohio, he was the son of labor organizers. Whether through this early influence or an early life that was not always tranquil or easy, by his twenties Phillips demonstrated a lifelong concern with the living conditions of working people. He was a proud member of the Industrial Workers of the World, popularly known as "the Wobblies," an organizational artifact of early twentieth-century labor struggles that has seen renewed interest and growth in membership in the last decade, not in small part due to his efforts to popularize it.

Phillips served as an Army private during the Korean War, an experience he would later refer to as the turning point of his life. Deeply affected by the devastation and human misery he had witnessed, upon his return to the United States he began drifting, riding freight trains around the country. His struggle would be familiar today, when the difficulties of returning combat veterans are more widely understood, but in the late fifties Phillips was left to work them out for himself. Destitute and drinking, Phillips got off a freight train in Salt Lake City and wound up at the Joe Hill House, a homeless shelter operated by the anarchist Ammon Hennacy, a member of the Catholic Worker movement and associate of Dorothy Day.

Phillips credited Hennacy and other social reformers he referred to as his "elders" with having provided a philosophical framework around which he later constructed songs and stories he intended as a template his audiences could employ to understand their own political and working lives. They were often hilarious, sometimes sad, but never shallow.

"He made me understand that music must be more than cotton candy for the ears," said John McCutcheon, a nationally-known folksinger and close friend. In the creation of his performing persona and work, Phillips drew from influences as diverse as Borscht Belt comedian Myron Cohen, folksingers Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, and Country stars Hank Williams and T. Texas Tyler.

A stint as an archivist for the State of Utah in the 1960s taught Phillips the discipline of historical research; beneath the simplest and most folksy of his songs was a rigorous attention to detail and a strong and carefully-crafted narrative structure. He was a voracious reader in a surprising variety of fields. Meanwhile, Phillips was working at Hennacy's Joe Hill house. In 1968 he ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket. The race was won by a Republican candidate, and Phillips was seen by some Democrats as having split the vote. He subsequently lost his job with the State of Utah, a process he described as "blacklisting."

Phillips left Utah for Saratoga Springs, New York, where he was welcomed into a lively community of folk performers centered at the Caffé Lena, operated by Lena Spencer. "It was the coffeehouse, the place to perform. Everybody went there. She fed everybody," said John "Che" Greenwood, a fellow performer and friend. Over the span of the nearly four decades that followed, Phillips worked in what he referred to as "the Trade," developing an audience of hundreds of thousands and performing in large and small cities throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. His performing partners included Rosalie Sorrels, Kate Wolf, John McCutcheon and Ani DiFranco.

"He was like an alchemist," said Sorrels, "He took the stories of working people and railroad bums and he built them into work that was influenced by writers like Thomas Wolfe, but then he gave it back, he put it in language so the people whom the songs and stories were about still had them, still owned them. He didn't believe in stealing culture from the people it was about."

A single from Phillips's first record, "Moose Turd Pie," a rollicking story about working on a railroad track gang, saw extensive airplay in 1973. From then on, Phillips had work on the road. His extensive writing and recording career included two albums with Ani DiFranco which earned a Grammy nomination. Phillips's songs were performed and recorded by Emmylou Harris, Waylon Jennings, Joan Baez, Tom Waits, Joe Ely and others. He was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Folk Alliance in 1997.

Phillips, something of a perfectionist, claimed that he never lost his stage fright before performances. He didn't want to lose it, he said; it kept him improving. Phillips began suffering from the effects of chronic heart disease in 2004, and as his illness kept him off the road at times, he started a nationally syndicated folk-music radio show, "Loafer's Glory," produced at KVMR-FM and started a homeless shelter in his rural home county, where down-on-their-luck men and women were sleeping under the manzanita brush at the edge of town. Hospitality House opened in 2005 and continues to house 25 to 30 guests a night. In this way, Phillips returned to the work of his mentor Hennacy in the last four years of his life.

Phillips died at home, in bed, in his sleep, next to his wife. He is survived by his son Duncan and daughter-in-law Bobette of Salt Lake City, son Brendan of Olympia, Washington; daughter Morrigan Belle of Washington, D.C.; stepson Nicholas Tomb of Monterrey, California; stepson and daughter-in-law Ian Durfee and Mary Creasey of Davis, California; brothers David Phillips of Fairfield, California, Ed Phillips of Cleveland, Ohio and Stuart Cohen of Los Angeles; sister Deborah Cohen of Lisbon, Portugal; and a grandchild, Brendan. He was preceded in death by his father Edwin Phillips and mother Kathleen, and his stepfather, Syd Cohen.

The family requests memorial donations to Hospitality House, P.O. Box 3223, Grass Valley, California 95945 (530) 271-7144 http://www.hospitalityhouseshelter.org

the Rio Theater Santa Cruz Ca. featuring Faith Petric, The Devil Makes 3 & U Utah Phillips and various FRSC programmers

Critical Mass Radio Network: live broadcast from 01-28-05

http://radio.indymedia.org/en/node/3540

mp3

http://radio.indymedia.org/sites/radio.indymedia.org/files/cmrn_frsc_benifit012805pt2.mp3

Part 1

http://radio.indymedia.org/en/node/3543

I learned in Korea that I would never again in my life abdicate to somebody else my right and my ability to decide who the enemy is. Got back from Korea; I was so mad at what I'd seen and done I wasn't sure I could ever live in the country again. I got on the freight trains up in Everett, north of Seattle, and kind of cruised the country for two years makin' up songs, but I was drunk most of the time and forgot most of those.

I'd heard that there was a house in Salt Lake City by the roper yards... where there was a clothing barrel and free food. So I, I got off the train there. I was headed for Salt Lake anyway.

I found that house right where they said it was, but most of all I found this, this wiry old man, sixty-nine years old. Tougher'n nails, heart of gold, fella by the name of Ammon Hennacy. Anybody know that name? Ammon Hennacy? One of Dorothy Day's people, the Catholic workers, during the Thirties they started houses of hospitality all over the country; there're about eighty of 'em now.

Ammon Hennacy was one of those; he'd come west to start this house I'd found called The Joe Hill House of Hospitality. Ammon Hennacy was a Catholic anarchist, pacifist, draft-dodger of two World Wars, tax refuser, vegetarian, one-man revolution in America - I think that about covers it.

First thing he said, after he got to know me, he said: "You know you love the country. You love it. You come in and out of town on those trains singin' songs about different places and beautiful people. You know you love the country; you just can't stand the government. Get it straight." He quoted Mark Twain to me: "Loyalty to the country always; loyalty to the government when it deserves it." It was an essential distinction I had been neglecting.

And then he had to reach out and grapple with the violence, but he did that with all the people around him. These second World War vets, you know, on medical disabilities and all drunked up; the house was filled with violence, which Ammon, as a pacifist, dealt with - every moment, every day of his life. He said, "You got to be a pacifist." I said, "Why?" He said, "It'll save your

life." And my behavior was very violent then.

I said, "What is it?" And he said, "Well I can't give you a book by Gandhi - you wouldn't understand it. I can't give you a list of rules that if you sign it you're a pacifist." He said, "You look at it like booze. You know, alcoholism will kill somebody, until they finally get the courage to sit in a circle of people like that and put their hand up in the air and say, 'Hi, my name's Utah, I'm an alcoholic.' And then you can begin to deal with the behavior, you see, and have the people define it for you whose lives you've destroyed."

He said, "It's the same with violence. You know, an alcoholic, they can be dry for twenty years; they're never gonna sit in that circle and put their hand up and say, 'Well, I'm not alcoholic anymore' - no, they're still gonna put their hand up and say, 'Hi, my name's Utah, I'm an alcoholic.' It's the same with violence. You gotta be able to put your hand in the air and acknowledge your

capacity for violence, and then deal with the behavior, and have the people whose lives you messed with define that behavior for you, you see. And it's not gonna go away - you're gonna be dealing with it every moment in every situation for the rest of your life."

I said, "Okay, I'll try that," and Ammon said "It's not enough!"

I said: "Oh."

He said, "You were born a white man in mid-twentieth century industrial America. You came into the world armed to the teeth with an arsenal of weapons. The weapons of privilege, racial privilege, sexual privilege, economic privilege. You wanna be a pacifist, it's not just giving up guns and knives and clubs and fists and angry words, but giving up the weapons of privilege, and going into the world completely disarmed. Try that."

That old man has been gone now twenty years, and I'm still at it. But I figure if there's a worthwhile struggle in my own life, that, that's probably the one. Think about it.

I'd always wanted to write a song for that old man. He never wanted one about him - he's that way - but something mulched up out of his thought, his anarchist thought. Anarchist in the best sense of the word. Oh so many times he stood up in front of Federal District Judge Ritter, that old fart, and he'd be picked up for picketing illegally, and he never plead innocent or guilty -

he plead anarchy.

And Ritter'd say, "What's an anarchist, Hennacy?" and Ammon would say, "Why an anarchist is anybody who doesn't need a cop to tell him what to do." Kind of a fundamentalist anarchist, huh?

And Ritter'd say, "But Ammon, you broke the law, what about that?" and Ammon'd say, "Oh, Judge, your damn laws the good people don't need 'em and the bad people don't obey 'em so what use are they?"

Well I lived there for eight years, and I watched him, really watched him, and I discovered watching him that anarchy is not a noun, but an adjective. It describes the tension between moral autonomy and political authority, especially in the area of combinations, whether they're going to be voluntary or coercive. The most destructive, coercive combinations are arrived at through force.

Like Ammon said, "Force is the weapon of the weak."

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.