From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

State Narcotics Agent to Go on Trial for Murder in Cardenas Case September 26

On September 26, State Agent Michael Walker will go on trial in San Jose for the killing of Rodolfo "Rudy" Cardenas.

On the afternoon of February 17, 2004, California Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement undercover agent Michael Walker sat in a car outside the San Jose home of a wanted parole violator named David Gonzales, waiting for him to show up. The stakeout included other Narcotics agents and agents of the State Parole Fugitive Apprehension Team. Walker did not have a photo of Gonzales, and had only a rough idea of what he looked like—Latino, of medium build, with a moustache. He knew Gonzales had once done prison time for assault with a deadly weapon and considered him dangerous.

The 33-year old Walker had joined the Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement almost two years earlier, after 11 years on the force of the Watsonville Police, where he was a patrol officer. In 2002 a woman filed an unreasonable force claim against him in which he was said to have failed to give her adequate medical attention after other officers injured her. A jury cleared him in that case.

A van pulled up in front of Gonzales’ house at 1:10 p.m. and then quickly drove off again. The driver of the van was 43 year-old Rodolfo “Rudy” Cardenas of San Jose. Walker and other agents thought he fit the description of Gonzales and began to follow him. Cardenas tried to get away and a chase ensued.

Police communications were scrambled. The agents were not able to communicate on police radio, and could not check the license plate of the van to identify the driver. They informed the San Jose Police Department they were on a chase by calling 911 on a cell phone. SJPD officers who spotted them wondered what they were doing tearing wildly around downtown.

Cardenas finally ditched his van, ran through an alley and jumped a fence into a parking lot to get away. Walker, giving chase on foot, came up to the fence, aimed his Glock .40-caliber semi-automatic pistol through the chain link, and shot Cardenas in the back from at least 35 feet away. The bullet punctured a major artery. By the time Walker realized Cardenas was not Gonzales, Cardenas was already dead at San Jose Medical Center. Gonzales was arrested later that day without incident. In a savage twist to a tragic story, treatment of Cardenas at the scene was delayed ten minutes. There was a dispatch error, police say, and paramedics were kept away. As Cardenas bled to death, police were walking around him, snapping pictures and collecting evidence, apparently inured to his mortal agony.

Cardenas was married and had five children, along with a warm extended family. Their loss was almost too much for them to bear. When the police arrived at the Cardenas home, a long while after the killing, they badgered the family with questions about Rudy’s mental state and drug use instead of giving an explanation of what happened. This deepened the family’s outrage.

Jesse Villarreal, Rudy Cardenas’ nephew, was already an activist against police brutality. Additionally, Rudy’s daughters Corina Saenz and Regina Cardenas and his niece, Juanita Villarreal, became activists in the wake of his killing. Juanita was quoted in the San Jose Mercury News the day after Rudy died: “It’s not right, it’s ridiculous. How can you kill somebody if they’re running from you? I don’t have an uncle; my cousins don’t have a father, all because of a mistake. They go around chasing and scaring people, and for what?”

The Cardenas family connected with the family and supporters of Bich Cau Thi Tran, a young Vietnamese mother who was shot to death in her kitchen by an SJPD officer in July 2003 because she was waving a vegetable peeler the officer said he thought was a cleaver. The Vietnamese community raised their voices enough around that case to get an open Grand Jury hearing, and although the officer who shot Tran was exonerated, a precedent was set. The Grand Jury always looked into every officer-involved killing in Santa Clara County, but usually their hearings were held away from the public eye. Activists feel there is a much greater chance of an officer being indicted when the Grand Jury is open to the public and the press, so that was what the Cardenas family tried to see happen.

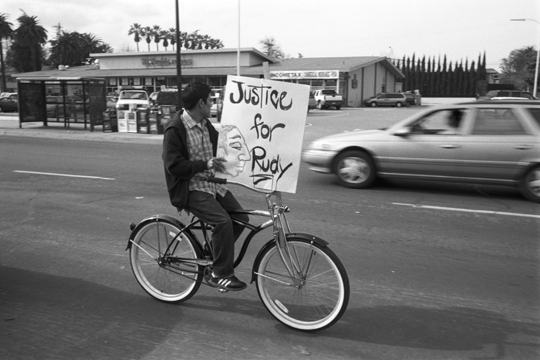

A “Justice for Rudy” movement was started, and their heartfelt vigils and demonstrations were widely reported. Yet the press also discounted Cardenas’ innocence with spin intended to make him look responsible for what happened. In this way it was reported he had been in Folsom and Pelican Bay prisons on drug charges and that he was under the influence of methamphetamine at the time of his death. His brother Raúl Cardenas responded in the Mercury News: “He was trying so hard to get back in the mainstream. It was kind of hard for him. He was never given a chance. Now, to think this beautiful person was shot in the back. This man, he was no killer.” Rudy had paid his dues—he had finished his parole—and was about to start a job with a moving company. He was happy, said his brother Alfred.

The Cardenas family filed a wrongful death suit on June 12, 2004, naming the state of California and Michael Walker, which asks an undetermined amount in damages. Often civil cases can be won when criminal charges against police are inadequately prosecuted. But when the Grand Jury hearing took place, an indictment against Walker for manslaughter came through, much to the relief of the family and their supporters. Raúl Cardenas kissed the steps of the courthouse and formed a V with his fingers. He told the press, “Justice has been served in Santa Clara County today. At least now they can see you better be careful when you pull the trigger.”

In the course of the Grand Jury hearing, two arguments surfaced that will likely shape the trial when it takes place. For the prosecution, there is the strong argument that Cardenas was not a threat to Walker. In the testimony of Walker’s supervisor, it came out that Walker reported the day of the killing that he was not sure Cardenas had a gun. Another State Narcotics Agent, Cesar Sanchez, testified that Walker could have sought cover behind a wall if he had felt threatened by Cardenas, something Sanchez did at the time of the shooting. Also there was testimony from Gonzalez’ parole officer that he was not actually a threat to police.

For his part, in the hearing Walker backtracked on what he told his supervisor, and insisted he was clear that Cardenas was turning around with what looked like a gun. Walker said what he saw in Cardenas’ hand was likely a four-inch knife found by a crime scene investigator. However, this knife was not found in either of two pat-down searches of Cardenas. It was found later in Cardenas’ clothes, which were thrown in a heap at the crime scene. There were no fingerprints on the knife, and although the clothes were soaked with blood, there was not much blood on it. Thus the knife is not a strong piece of evidence, and may not help Walker.

A “suicide by cop” scenario will likely be manufactured by the defense. Jeanette Cardenas, Rudy’s wife, told the Grand Jury that Rudy, who was wanted on a domestic violence warrant because she had made a complaint, had told her that in reaction to her making the complaint he wanted to bring the police out to shoot him. However, when facing a line of questioning on this issue, she insisted tearfully, “What you’re trying to ask me has nothing to do with what happened.” She said she and her husband were planning to get back together and try to make the relationship work. District Attorney Lane Liroff, who played a major role in the Grand Jury hearing, treated the suicide theory with sarcasm. He said in the Mercury News: “This may be the first instance of suicide by cop where the person is running away.”

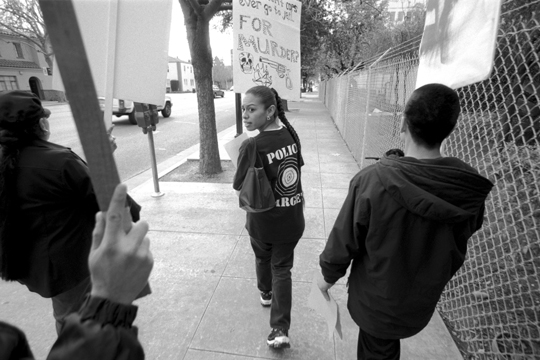

The Cardenas family, who attended the hearing dressed in black, are readying themselves for the trial. The Santa Clara County Human Relations Commission, responsible for addressing human rights concerns, helped the family in the months leading up to the hearing. The Chair of the Commission, Debra Dake, told me late last year: “The young people in the Cardenas family have been just phenomenally powerful and effective … their phenomenal spirit has gone undaunted and they haven’t become cynical.” Addressing the Commission this spring, Corina Saenz remarked, “I wish I wasn’t here … I wish my dad was here with us. Before the event [of Rudy’s death] I was an average 20 year-old, working and going to school. Now my eyes have been opened to the way the system works.” It seemed natural for Corina, Regina, Jesse and Juanita to attend meetings and demonstrations of a number of San Jose groups protesting police brutality. Said Dake, “They are still fighting for justice in all arenas; they just didn’t let it die with their dad and their uncle—they carried it forward.”

In a poignant moment I sat with Jesse Villarreal on a bench in San Jose’s Roosevelt Park, just before a small march, commemorating the first year since Cardenas’ death, wound around downtown near where he was killed. “I think about how fun he was,” Villarreal said, “how he was always kidding around, having a good time. He was always a good person to be around. And so in times like this I think of him and remember his smile, the way he used to look at you. People who knew him knew about the way he used to have a little smile on his face. You know, one of those smiles that is one in a million.”

We will soon see what will happen to Michael Walker. For extinguishing the life of Rudy Cardenas he faces up to an 11-year sentence. Yet the tradition of police shooting first and asking questions later is hard to buck. Santa Clara County will watch what takes place, hoping justice will be served, and hanging on this judgment as a sign of things to come.

The 33-year old Walker had joined the Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement almost two years earlier, after 11 years on the force of the Watsonville Police, where he was a patrol officer. In 2002 a woman filed an unreasonable force claim against him in which he was said to have failed to give her adequate medical attention after other officers injured her. A jury cleared him in that case.

A van pulled up in front of Gonzales’ house at 1:10 p.m. and then quickly drove off again. The driver of the van was 43 year-old Rodolfo “Rudy” Cardenas of San Jose. Walker and other agents thought he fit the description of Gonzales and began to follow him. Cardenas tried to get away and a chase ensued.

Police communications were scrambled. The agents were not able to communicate on police radio, and could not check the license plate of the van to identify the driver. They informed the San Jose Police Department they were on a chase by calling 911 on a cell phone. SJPD officers who spotted them wondered what they were doing tearing wildly around downtown.

Cardenas finally ditched his van, ran through an alley and jumped a fence into a parking lot to get away. Walker, giving chase on foot, came up to the fence, aimed his Glock .40-caliber semi-automatic pistol through the chain link, and shot Cardenas in the back from at least 35 feet away. The bullet punctured a major artery. By the time Walker realized Cardenas was not Gonzales, Cardenas was already dead at San Jose Medical Center. Gonzales was arrested later that day without incident. In a savage twist to a tragic story, treatment of Cardenas at the scene was delayed ten minutes. There was a dispatch error, police say, and paramedics were kept away. As Cardenas bled to death, police were walking around him, snapping pictures and collecting evidence, apparently inured to his mortal agony.

Cardenas was married and had five children, along with a warm extended family. Their loss was almost too much for them to bear. When the police arrived at the Cardenas home, a long while after the killing, they badgered the family with questions about Rudy’s mental state and drug use instead of giving an explanation of what happened. This deepened the family’s outrage.

Jesse Villarreal, Rudy Cardenas’ nephew, was already an activist against police brutality. Additionally, Rudy’s daughters Corina Saenz and Regina Cardenas and his niece, Juanita Villarreal, became activists in the wake of his killing. Juanita was quoted in the San Jose Mercury News the day after Rudy died: “It’s not right, it’s ridiculous. How can you kill somebody if they’re running from you? I don’t have an uncle; my cousins don’t have a father, all because of a mistake. They go around chasing and scaring people, and for what?”

The Cardenas family connected with the family and supporters of Bich Cau Thi Tran, a young Vietnamese mother who was shot to death in her kitchen by an SJPD officer in July 2003 because she was waving a vegetable peeler the officer said he thought was a cleaver. The Vietnamese community raised their voices enough around that case to get an open Grand Jury hearing, and although the officer who shot Tran was exonerated, a precedent was set. The Grand Jury always looked into every officer-involved killing in Santa Clara County, but usually their hearings were held away from the public eye. Activists feel there is a much greater chance of an officer being indicted when the Grand Jury is open to the public and the press, so that was what the Cardenas family tried to see happen.

A “Justice for Rudy” movement was started, and their heartfelt vigils and demonstrations were widely reported. Yet the press also discounted Cardenas’ innocence with spin intended to make him look responsible for what happened. In this way it was reported he had been in Folsom and Pelican Bay prisons on drug charges and that he was under the influence of methamphetamine at the time of his death. His brother Raúl Cardenas responded in the Mercury News: “He was trying so hard to get back in the mainstream. It was kind of hard for him. He was never given a chance. Now, to think this beautiful person was shot in the back. This man, he was no killer.” Rudy had paid his dues—he had finished his parole—and was about to start a job with a moving company. He was happy, said his brother Alfred.

The Cardenas family filed a wrongful death suit on June 12, 2004, naming the state of California and Michael Walker, which asks an undetermined amount in damages. Often civil cases can be won when criminal charges against police are inadequately prosecuted. But when the Grand Jury hearing took place, an indictment against Walker for manslaughter came through, much to the relief of the family and their supporters. Raúl Cardenas kissed the steps of the courthouse and formed a V with his fingers. He told the press, “Justice has been served in Santa Clara County today. At least now they can see you better be careful when you pull the trigger.”

In the course of the Grand Jury hearing, two arguments surfaced that will likely shape the trial when it takes place. For the prosecution, there is the strong argument that Cardenas was not a threat to Walker. In the testimony of Walker’s supervisor, it came out that Walker reported the day of the killing that he was not sure Cardenas had a gun. Another State Narcotics Agent, Cesar Sanchez, testified that Walker could have sought cover behind a wall if he had felt threatened by Cardenas, something Sanchez did at the time of the shooting. Also there was testimony from Gonzalez’ parole officer that he was not actually a threat to police.

For his part, in the hearing Walker backtracked on what he told his supervisor, and insisted he was clear that Cardenas was turning around with what looked like a gun. Walker said what he saw in Cardenas’ hand was likely a four-inch knife found by a crime scene investigator. However, this knife was not found in either of two pat-down searches of Cardenas. It was found later in Cardenas’ clothes, which were thrown in a heap at the crime scene. There were no fingerprints on the knife, and although the clothes were soaked with blood, there was not much blood on it. Thus the knife is not a strong piece of evidence, and may not help Walker.

A “suicide by cop” scenario will likely be manufactured by the defense. Jeanette Cardenas, Rudy’s wife, told the Grand Jury that Rudy, who was wanted on a domestic violence warrant because she had made a complaint, had told her that in reaction to her making the complaint he wanted to bring the police out to shoot him. However, when facing a line of questioning on this issue, she insisted tearfully, “What you’re trying to ask me has nothing to do with what happened.” She said she and her husband were planning to get back together and try to make the relationship work. District Attorney Lane Liroff, who played a major role in the Grand Jury hearing, treated the suicide theory with sarcasm. He said in the Mercury News: “This may be the first instance of suicide by cop where the person is running away.”

The Cardenas family, who attended the hearing dressed in black, are readying themselves for the trial. The Santa Clara County Human Relations Commission, responsible for addressing human rights concerns, helped the family in the months leading up to the hearing. The Chair of the Commission, Debra Dake, told me late last year: “The young people in the Cardenas family have been just phenomenally powerful and effective … their phenomenal spirit has gone undaunted and they haven’t become cynical.” Addressing the Commission this spring, Corina Saenz remarked, “I wish I wasn’t here … I wish my dad was here with us. Before the event [of Rudy’s death] I was an average 20 year-old, working and going to school. Now my eyes have been opened to the way the system works.” It seemed natural for Corina, Regina, Jesse and Juanita to attend meetings and demonstrations of a number of San Jose groups protesting police brutality. Said Dake, “They are still fighting for justice in all arenas; they just didn’t let it die with their dad and their uncle—they carried it forward.”

In a poignant moment I sat with Jesse Villarreal on a bench in San Jose’s Roosevelt Park, just before a small march, commemorating the first year since Cardenas’ death, wound around downtown near where he was killed. “I think about how fun he was,” Villarreal said, “how he was always kidding around, having a good time. He was always a good person to be around. And so in times like this I think of him and remember his smile, the way he used to look at you. People who knew him knew about the way he used to have a little smile on his face. You know, one of those smiles that is one in a million.”

We will soon see what will happen to Michael Walker. For extinguishing the life of Rudy Cardenas he faces up to an 11-year sentence. Yet the tradition of police shooting first and asking questions later is hard to buck. Santa Clara County will watch what takes place, hoping justice will be served, and hanging on this judgment as a sign of things to come.

Add Your Comments

Latest Comments

Listed below are the latest comments about this post.

These comments are submitted anonymously by website visitors.

TITLE

AUTHOR

DATE

DONT GIVE UP!

Mon, Oct 17, 2005 7:15PM

JUSTICE

Fri, Aug 26, 2005 10:01AM

State Narcotics Agent to Go on Trial

Thu, Aug 25, 2005 11:03PM

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network