From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

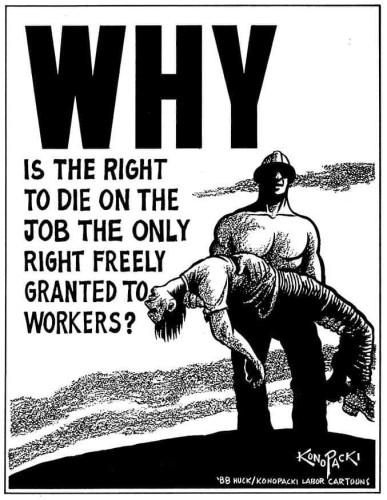

Injured Workers Panel On Injured Workers, Workers Comp, OSHA, Healthcare & Workers Rights

Date:

Saturday, July 27, 2024

Time:

10:00 AM

-

1:00 PM

Event Type:

Class/Workshop

Organizer/Author:

Injured Workers Unite

Location Details:

ILWU Local 6, 99 Hegenberger Rd., Oakland

7/27/24 Panel On Injured Workers, Workers Comp, OSHA, Healthcare & Workers Rights

Workers and health and safety advocates will speak out about the attack on health and safety on the job and the corruption of the workers compensation system as well as the capture of government agencies by employers that are supposed to be protecting workers on the job and injured workers

Saturday July 27 @ 10:00 am - 1:00 pm PDT

FREE

At: ILWU Local 6 – 99 Hegenberger Rd. Oakland

There are less than 200 OSHA inspectors for the 18 million workers of California. The Covid pandemic led to the deaths of many workers at food processing companies like Foster farms and many nursing homes because of a failure to provide PPE and educate the workers. Additionally seriously injured workers face a gauntlet of obstacles getting prompt medical treatment and workers compensation. Many workers say that workers comp has been captured by the employers, insurance companies and a State and Federal administration that is representing this interests rather than workers. Workers from the ILWU and other unions as well as advocates fighting for workers compensation and health and safety will speak out.

They will report on this crisis and how it is destroying workers and their families.

Speakers:

Injured Workers Unite

Rank and File Workers

Desiree Rojas – President, Labor Council For Latin American Advancement Sacramento Chapter, and others

Sponsored by WorkWeek

Additional Media:

Demo Gov Newsom Attacks Labor Reps On OSHA Board-Helping Bosses Injure & Murder Workers

Newsom shakes up workplace safety board that bucked him on heat rules

https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/newsom-california-safety-board-19515018.php

By Jeanne Kuang

June 16, 2024

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed indoor heat protection rule this year.

Jessica Christian/The Chronicle 2022

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed heat protection rule this year.

The shake-up comes less than two weeks before the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board is expected to approve the rule, requiring businesses to shield their indoor workers from the risks of extreme heat. The state spent years developing the proposal, only for its approval to be further delayed in March when Newsom’s administration withdrew its support the day before a scheduled vote over cost concerns.

The two members who were recently reshuffled were among those most outspoken on the administration’s last-minute move, which pushed back the rule so that it has not gone into effect in time for the first of this summer’s heat waves.

ADVERTISEMENT

Article continues below this ad

During the March meeting, board member Laura Stock called the action “completely outrageous” and said it “undermines” the board, while Chairperson Dave Thomas said the administration “set us up.” Thomas suggested taking a largely symbolic vote to pass the rule anyway, in a public rebuke of the administration. His motion passed, unanimously.

Stock said she got a call last Friday from an appointments official in Newsom’s office telling her she was off the board, effective immediately, with no explanation.

“It was very shocking. There was no indication that anything like this was planned,” Stock told CalMatters of the call. “I was simply told the governor decided to move in a different direction.”

More For You

Gov. Newsom halts effort to protect California workers from indoor heat, citing cost

Arjun Kandel makes chicken curry at Himalayan Pizza and Momo Wednesday, Sept. 12, 2018 in San Francisco, Calif.

Newsom offers compromise to protect indoor workers from heat, but some will have to wait

Franky Ho, front to back, co-owner Four Kings, prepares a dish in a wok as Mike Long, grills a Xin Jiang lamb skewer in the kitchen at Four Kings on Monday, February 26, 2024 in San Francisco, Calif.

Newsom also replaced Thomas as chairperson with board member Joseph Alioto, an antitrust attorney, the governor’s office confirmed. Thomas, president of a Northern California construction union, remains a board member. He did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Stock, a researcher and director of the Labor Occupational Health Program at UC Berkeley, held a seat reserved for workplace safety experts on the seven-member board since 2012.

Her latest reappointment was in 2020, and expired last June. It is not uncommon for state board and commission members to serve for months on expired terms before the governor’s office reappoints or replaces them. Two other workplace safety board members — a labor representative and an employers’ representative — are also still serving on terms that expired last June.

Alex Stack, a spokesperson for Newsom, wrote in an email that his office would not “comment further on personnel matters.” No replacement for Stock had been appointed as of Friday.

Stock said she did not want to speculate on the reasons for her removal and said she was proud of her work on the board. “The board passed what I consider groundbreaking, cutting-edge, essential regulations protecting workers from sometimes life-threatening hazards,” she said.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed indoor heat protection rule this year.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed indoor heat protection rule this year.

Michael Macor/The Chronicle 2017

But worker advocates said they are concerned about the removals.

Stephen Knight, executive director of the advocacy group Worksafe, praised Stock as “one of the most experienced voices for worker health and safety” and Thomas for leading the board through the COVID-19 pandemic. In those years, the board considered renewals of an emergency rule to reduce transmission of the virus in worksites, amid intense public backlash from proponents of reopening businesses.

“If the governor has a direction or vision for worker health and safety, it’s not one that he’s articulated, and we’re all ears,” Knight said. “We’re concerned about what these surprise removals may mean about the governor’s commitment to worker health and safety, and climate justice.”

Administration officials have said they pulled their support from the indoor heat rule in March after discovering the rule would cost state prisons billions more dollars than the workplace safety agency estimated. But it has so far refused to disclose its cost estimates and denied a CalMatters request for public records relating to the costs.

The rule the board is scheduled to vote on Thursday is an amended version that exempts state prisons.

Jeanne Kuang covers labor, politics and California’s state government for CalMatters, where this article first appeared. Reach her at jeanne [at] calmatters.org.

June 16, 2024

Jeanne Kuang

Labor Supported Gov Newsom Attacks Labor Reps On OSHA Standards Board

by Garrett Brown

The crisis in California’s worker protection agencies has deepened in the last week as Governor Gavin Newsom removed one pro-worker Board member, and demoted the labor representative serving as Chair, of the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board.

Board member Laura Stock, Director of the Labor Occupational Health Program at UC Berkeley and on the Board for 12 years, was summarily dismissed by the Governor’s Appointments Office on June 7th. Union official Dave Thomas was demoted from Chair and remains on the Board. The new Board chair is attorney Joseph Alioto, who has no known expertise or knowledge of workplace health and safety, but is a longtime political operative appointed to the Board by Newsom earlier this year.

The crimes committed by Stock and Thomas apparently were in opposing Newsom’s efforts to further delay a regulation to protect workers from indoor heat which has been years in the making. The Governor’s Appointments office told Stock that Newsom wanted her off the Board because the Governor “wants to go in a new direction.”

The employer community has applauded the removal of Stock, no doubt raising Newsom’s “business-friendly” status for his future political campaigns.

Meanwhile, the “new direction” in staffing Cal/OSHA’s enforcement inspectorate is more vacancies among field compliance officers. According to the latest available data, on March 1, 2024, Cal/OSHA’s vacancy rate for field compliance inspectors reached 39% with 109 vacancies. If the 11 compliance safety and health officer (CSHO) positions being held in reserve are included in the tally, then Cal/OSHA’s inspector vacancies reach 41% with 120 CSHO vacancies.

The debilitating gaps in workplace health and safety coverage are clearest at the local level. Nineenforcement District Offices have CSHO vacancy rates at or above 40% -- Santa Ana (73%), San Francisco (66%), San Bernardino (64%) and Fremont (64%), American Canyon (55%), Bakersfield (50%) and Long Beach (50%), Sacramento (45%), and Fresno (42%).

Another three District Offices have CSHO vacancy rates between 33% and 40% -- Los Angeles, Oakland, and Foster City. This means that a dozen Cal/OSHA District Offices have crippling vacancies that severely undermine safety protections for California’s 19 million workers.

The California Employment Development Department (EDD) reported the California civilian labor force in March 2024 as 19,346,200 workers. The 162.5 field-available CSHO positions represents an inspector to worker ratio of 1 inspector to 119,053 workers. Cal/OSHA’s inspector to worker ratio of 1 inspector to119,000 workers is much less health protective than Washington State’s ratio of 1 to 26,000, and Oregon’s ratio of 1 to 24,000.

There are also key manager vacancies with no Region III Manager (Los Angeles-Orange County), and no District Managers for the Fresno and Monrovia offices. There are two District Offices – Los Angeles and the Concord PSM – with zero clerical staff, which means that CSHOs must spend time doing administrative work.

There are only 10 field enforcement positions for PSM refinery unit covering the state’s 15 oil refineries, and four of those positions are vacant.

According to the Cal/OSHA’s “Organization Chart,” there are only 15 CSHOs classified as “bilingual,” and Region II (Central Valley) has no bilingual field inspectors.

Cal/OSHA has only six (6) industrial hygienists among field inspectors – with none in Region I (San Francisco), Region IV (Los Angeles), and the PSM unit. Industrial hygienists are needed to conduct “health” inspections to evaluate harmful exposures to hazardous chemicals, noise and heat, ergonomics and repetitive motions. Cal/OSHA has brand new standards to protect workers against airborne silica and lead, as well as heat exposures in a changing climate – but now has only extremely limited capacity to conduct effective industrial hygiene inspections.

Cal/OSHA’s Legal Unit has an attorney vacancy rate of 15% (5 of 34 positions) at a time of increased employer appeals of enforcement citations requiring corrective action to protect workers.

Meanwhile, Cal/OSHA’s “Bureau of Investigation” (BOI) which investigates and refers to county District Attorneys cases that trigger possible criminal charges has only one investigator for the entire state – and five vacancies. The once-feared BOI unit has lost virtually all of its deterrent impact with near-zero referrals for fatal accidents and multiple injury events.

Cal/OSHA’s Consultation Service – which provides free service to employers, especially small employers unfamiliar with workplace health and safety – also has a 50% vacancy rate for field personnel (18 out of 36 positions). As new regulations go into effect, such as the recently enacted lead and silica standards, the Consultation Service will be able to assist far fewer employers.

In recent months there has been damning publicity about the years-long staffing crisis and its impact on workers in California in the Los Angeles Times and Sacramento Bee, journalism websites CalMatters and Capital & Main, and public radio stations like KQED in San Francisco.

Nonetheless, California’s Governor, Labor Secretary, and Director of the Department of Industrial Relations have failed to end the field inspector vacancy crisis and protect California workers from irresponsible employers.

Best, Garrett Brown

Newsom Dismisses Workplace Safety Regulator Ahead of Important Vote

By Farida Jhabvala Romero Jun 12

Save Article

Cook Giovanni Gomez preparing chicken on the grill for food orders in the busy kitchen of the El Pollo Loco restaurant in Agoura Hills on Aug. 18, 2021. (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Gov. Gavin Newsom removed an outspoken occupational safety expert from

a powerful regulatory body that adopts California’s workplace safety rules.

In addition to ending Laura Stock’s term as a member of the Occupational Safety & Health Standards Board, Newsom demoted David Thomas, the former chairperson.

Several worker advocates told KQED they were suspicious of the shakeup with just over a week before the board is scheduled to vote on indoor heat illness prevention rules. They are worried that the board could become less protective of vulnerable workers.

“It’s concerning that a member like Laura Stock, who has so much expertise and is so committed to workplace health and safety, would be removed,” said Tim Shadix, legal director at the Warehouse Worker Resource Center, which is pushing for the indoor heat illness protections.

Newsom’s office confirmed that Stock is no longer on the workplace safety board. Joseph Alioto Jr., the San Francisco trial lawyer Newsom appointed last summer, was named chair. A spokesperson for the governor declined to comment on why

Newsom made the changes or when he’ll make an appointment to fill the vacant seat on the seven-member body.

Sponsored

In an interview with KQED, Stock said the governor’s office told her on June 7 that she was terminated from the board. When she asked for more information, according to Stock, the person only said that Newsom had “decided to go in a different direction.”

“I was shocked and surprised,” said Stock, who directs the Labor Occupational Health Program at UC Berkeley. “There had been no indication that this decision was coming.”

Stock spent 12 years on the board, contributing to the passage of life-saving protections for hazards such as COVID-19, lead poisoning and silica dust from engineered stone that has killed and disabled countertop fabrication workers.

“I was inspired by the many workers who had the courage to come and share their experiences and speak up about what was

needed to protect them on the job,” Stock said.

A representative of a large employer association did not lament Stock’s departure, claiming she often failed to listen to the concerns of member companies about proposed health and safety requirements.

“We as business stakeholders never really felt like Laura had any capacity for dispassionate analysis of the issues laid in front of her,” said the representative, who requested anonymity because they feared reprisal from Stock if she accepted another regulatory post. “She always had a position. You always knew how she’d vote. She never asked any questions of any criticism we would lay out.”

Heat illness protections for indoor workers have been delayed for years. In March, the board was expected to approve new requirements, but the Newsom administration withdrew its support seemingly at the last minute. Facing outrage from workers and their advocates, Stock and Thomas, a labor representative, openly criticized the move and called for a symbolic vote on the regulations. It passed unanimously.

Shadix questioned whether the board changes could be connected to those actions.

“It certainly seems a little bit suspicious and worrying that two of the members who were most outspoken for moving that indoor heat standard are now being demoted and removed,” he said. “We hope that this is not going to impact that being voted on and approved next week. Every summer that goes by without that standard in place, we see more suffering.”

‘Total system breakdown’: California firefighters with PTSD face a workers’ comp nightmare & LaborFest meeting on Injured Workers & OSHA

https://calmatters.org/environment/2024/06/california-firefighers-ptsd-workers-comp/

BY JULIE CART

JUNE 26, 2024

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Retired CalFire firefighter Todd Nelson in Nevada City on March 19, 2024. Nelson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from trauma experienced during his firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

Retired Cal Fire Captain Todd Nelson, shown in Nevada City, suffers from a severe case of post traumatic stress disorder resulting from his 28-year firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

IN SUMMARY

Even when suicidal, California firefighters struggle to find medical help and navigate the workers’ comp morass to pay for it. A 2021 analysis showed their claims were more likely to involve PTSD — and were denied more often.

Todd Nelson could feel it coming on. And he began to run. He was going dark again, retreating to a place where he would curl into a fetal position with his thumb in his mouth, watching from behind closed eyes as his personal reel of horror unspooled. Sights and sounds from three decades of firefighting cued up — shrieks from behind an impenetrable wall of flame, limbs severed in car accidents and the eyes of the terrified and the dead he was meant to save.

Nelson was running on the Foresthill Bridge, the highest in California, fleeing cops and firefighters after his wife reported that he was suicidal. He hurdled a concrete barrier and straddled the railing of the bridge in the Sierra Nevada foothills, staring down at a large rock 730 feet below. As the rescuers closed in, Nelson leaned precariously over the chasm. His strategy — making the fatal plunge appear accidental, allowing his family to collect his life insurance.

It was not Nelson’s first suicide attempt — the former Cal Fire captain had tried to take his life many times before. But after that 2021 ordeal, which led to an involuntary 72-hour psychiatric hold, something in him shifted. He was ready to admit that he had a problem and seek medical help.

The incident began the firefighter’s arduous, years-long journey toward wellness, threaded through a bureaucratic labyrinth strewn with more obstacles than he’d ever encountered on a California wildfire: finding qualified medical help, battling an insurance company to pay for it and navigating the tangled morass of California’s workers’ comp. All without going broke or returning to his dark place.

No one tracks how many of Cal Fire’s 12,000 firefighters and other employees suffer from mental health problems, but department leaders say post traumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts have become a silent epidemic at the agency responsible for fighting California’s increasingly erratic and destructive wildfires. In an online survey of wildland firefighters nationwide, about a third reported considering suicide and nearly 40% said they had colleagues who had committed suicide; many also reported depression and anxiety.

California’s workers’ comp — which is supposed to help people get medical treatment for workplace illnesses and injuries — can be a nightmare for firefighters and other first responders with PTSD.

Claims filed by firefighters and law enforcement officers are more likely to involve PTSD than claims by the average worker in California — and they have been denied more often than claims for other medical conditions, according to the research institute RAND.

From 2008 to 2019 in California, workers’ comp officials denied PTSD claims filed by firefighters and other first responders at more than twice the rate of their other work-related conditions, such as back injuries and pneumonia, RAND reported. About a quarter of firefighters’ 1,000 PTSD claims were denied, a higher rate than for PTSD claims from other California workers.

Become a CalMatters member today to stay informed, bolster our nonpartisan news and expand knowledge across California.

“It’s a fail-first system. You have to get a broken leg to show you are in need of support. With mental illness, we are constantly having to prove to everybody why we were ill. You have to get to the point of suicide,” said Jessica Cruz, the California chief executive officer of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Jennifer Alexander, Nelson’s therapist, said patients in acute crisis simply don’t have the mental capacity to ride herd on stubborn workers’ comp claims. Alexander said she was once on hold for more than six hours with Cal Fire’s mental health provider attempting to get one of her bills paid, and she has waited years to get paid for treating firefighters.

“People give up. It’s a battle… They are not fully functional,” said Alexander, who for 21 years has specialized in treating first responders with trauma and PTSD and has spent an estimated 25,000 hours treating them. “You are not talking about healthy individuals who can sit on the phone for hours.”

Cal Fire firefighters and other workers also have trouble finding qualified therapists, especially outside major cities in rural areas, where many are based. In 2021, less than half of people with a mental illness in the U.S. were able to access timely care. Therapists are reluctant to take workers’ comp, or sometimes any type of insurance. because they often have to wait months or years to be reimbursed.

Jennifer Alexander listens to Todd Nelsen during their session at Alexander's office in Gold River on April 24, 2024. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Therapist Jennifer Alexander listens to Nelson during a treatment session. She called workers’ comp a “total system breakdown.” Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Michael Dworsky, a senior economist at the research institute RAND and one of the study’s project leaders, called workers’ comp “challenging and bureaucratic.”

“Even if the claim is accepted, there can be disputes about the medical necessity of individual bills. Just because your claim is accepted, doesn’t mean you are done fighting with the insurance company,” he said.

A presumption of pain but still a tangled web

Employers in California must provide workers’ comp insurance that will pay for medical costs when a worker is injured on the job. But in reality, workers’ comp, which serves 16 million Californians, can be ungainly, confusing and, sometimes, no help at all. The system, administered by the state Department of Industrial Relations, is massive: In 2022 almost 750,000 workers’ comp claims were filed statewide.

When a firefighter requests coverage for medical treatment, insurance adjusters review the case to determine if it’s medically necessary. If the claim is denied, delayed or modified, a patient may request an independent medical review by so-called “ghost doctors” who review the case.

Systemwide in California, patients who appeal their denied workers’ comp claims, don’t fare well: Last year 3,238 appeals for mental health claims were filed, but workers’ comp officials rejected three-quarters of them, about the same as the 10-year average, according to data from the Department of Industrial Relations requested by CalMatters. (Agency officials said they could not provide data on claims from first responders.)

For decades, the California Legislature has wrestled with how to fix workers’ comp — in one year alone lawmakers proposed nearly two dozen bills.

In 2020 lawmakers took a major step, adding a legal shortcut or “presumption” to the statelabor code, stipulating that firefighters and other first responders are considered at high risk for PTSD in the course of doing their job.

That means first responders no longer carry the burden of proving their illness is work-related. However, a claims adjuster can still question the diagnosis or assert that the trauma was caused by other factors, such as military service or family events. A law enacted last year extended the presumption to 2029.

by Julie Cart

In practice, experts say that, despite the law, proving a mental health claim is still almost as difficult to overcome as the psychological injury itself. Break an arm while fighting a wildfire, and, backed up by x-rays, claims are approved. But break your mind after decades of exposure to on-the-job trauma? Prepare for battle.

Before enacting the law, state officials asked RAND researchers to report on the scope of the problem. They analyzed nearly 6 million claims filed between 2008 through 2019 and interviewed dozens of experts, including a representative sample of 13 first responders.

The researchers found a consistent and troubling trend among the 13: “Nearly all workers said that they had filed a workers' compensation claim for their mental health conditions — yet almost none received PTSD care paid for by workers' compensation.”

Paying out of pocket “caused severe financial strain in some cases. Some were eventually reimbursed by workers' compensation, but only after litigation and substantial delay. Some who pursued care through workers' compensation also noted that claim denials led to delays in the start of mental health treatment,” the RAND researchers wrote.

“Nearly all workers said that they had filed a workers' compensation claim for their mental health conditions — yet almost none received PTSD care paid for by workers' compensation.”

RAND REPORT

The 13 first responders they surveyed stressed “over and over again about self pay and barriers,” said Denise D. Quigley, a RAND senior policy researcher who was a project leader on the study. “It's not like we heard it once or twice, we heard it over and over again. It's highly unlikely that we talked to the (only) people in California that had this happen.”

Firefighters told of borrowing money from family members and taking out home equity loans to pay for care, Quigley said. The litany of their struggle weighed on her team. “It’s difficult to hear people break down crying while talking to us because of all the things they’ve seen.”

According to the RAND research, for the 12-year-period from 2008 through 2019, before the new law took effect:

Firefighters and other first responders were about twice as likely to file PTSD claims as the general workforce — but the numbers are small, under 1% of all workers' comp claims.

Firefighters’ PTSD claims were denied more often than claims of other workers: About 24% were denied, compared to about 19% of PTSD claims for all workers, including those in high-stress occupations. About a quarter of firefighter claims for all mental health conditions were denied.

Their PTSD claims were denied at more than twice the rate of their other presumptive medical conditions related to their jobs, such as hernias and back injuries. Even their cancer and heart disease claims were accepted at a higher rate than PTSD.

These denial rates were calculated using a sample of only 258 PTSD claims filed by firefighters. But researcher Dworsky said the total number of claims is far higher, about 1,000, with about 230 claims denied, during those 12 years. And countless other firefighters who suffer from PTSD didn’t seek care through workers’ comp.

The RAND report was the most detailed look at the inequities between how physical and mental health are treated among firefighters and how first responders’ claims were handled compared to other workers. But the researchers struggled with incomplete data and difficulty identifying which claims were from firefighters.

Quigley said she is frustrated that no one since has tracked whether the 4-year-old presumption law — known as the Trauma Treatment Act — has helped patients and improved the system.

Many therapists say they haven’t seen much, if any, improvement. Nelson’s therapist, Alexander, called workers’ comp a “total system breakdown.”

A spokesman for the Department of Industrial Relations refused to grant interview requests from CalMatters or answer questions or provide data about firefighters’ mental health claims.

Navigating the system

During his 28 years with Cal Fire fighting wildfires in combustible regions, such as the Napa Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills, and responding to other emergencies, Nelson never reported any mental health issues to anyone. Not once. Even as he would regularly pull his truck off the side of the road during wildfires and weep. Even after responding to the scene of traffic accidents, extricating children from crushed cars as their parents fought to get to them. Even after answering a call to a suicide to find a man hanging from the rafters in his barn. Even after the unbidden images began to intrude with greater frequency.

Instead, his mantra became “I’m good.”

That stoicism, common among first responders, short circuits the insurance system designed to help them — a system that works best with prompt reporting and meticulous documentation.

Claims adjusters usually handle clear-cut cases where the date of injury can be pinpointed. More common among PTSD claims, though, is Nelson’s experience with cumulative trauma, with no paper trail of injuries or complaints. He can’t offer a single event as the origin of his trauma and no coherent chronology. Cal Fire folks tend to wait until their dam bursts before asking for the water to be turned off.

One Southern California mental health provider told the RAND researchers that firefighters and police officers typically have severe cases of trauma.

“On the clinical side, as a mental health provider, it is not realistic to expect a firefighter or a police officer to come in and have had a little trauma or some minor stress condition…Most departments have people with a lot of stress and trauma,” the therapist said. “Just because you had something happen recently, the straw that broke the camel’s back, it is really the cumulative stress that is the issue.”

“Talk to anybody that tries to do anything through workers’ comp — it is an absolute nightmare. Everybody knows you file your first workers' comp claim and they will deny it."

BRAD NIVEN, CAL FIRE BATTALION CHIEF

Now retired, Nelson, 54, has been fighting for workers’ compensation for almost three years, since his suicide attempt on the Placer County bridge. He and his wife already have spent more than $10,000 out of pocket for medical care and could face thousands more in legal bills.

Nelson’s case is unusually severe and complex, requiring two extended stays in a facility that specifically treats firefighters to diagnose his conditions and finally set him on a treatment path of therapy and multiple medications.

Cal Fire Battalion Chief Brad Niven said he has more than a dozen firefighter friends who have had similar experiences.

“Talk to anybody that tries to do anything through workers’ comp — it is an absolute nightmare,” he said. “Everybody knows you file your first workers' comp claim and they will deny it. One guy I worked with went through the works with them. He had to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that you have problems. You have to relive everything you've gone through. It does not make for a friendly system.”

CalFire Battalion Chief Brad Niven at his home in Sonora on June 8, 2022. Photo by Julie Hotz for CalMatters

Cal Fire Battalion Chief Brad Niven, shown at his home in Sonora, said he and more than a dozen firefighter friends have had trouble getting workers' comp to pay their claims for mental health treatment.. Photo by Julie Hotz for CalMatters

Niven considered suicide before Cal Fire’s employee support personnel helped him find a therapist, streamlining what had been a hit-and-miss process.

“They blasted away the stumbling blocks,” he said. But the fire agency does not make the decision to approve or deny a claim or handle the bureaucratic thicket that is workers’ comp.

Scott O’Mara, a San Diego-based lawyer whose firm represents first responders, said adjusters’ training is to look for what they can develop to deny the case. “Their goal is to contain and control cost,” he said. “We do a lot of cases where the compensation is nickels.”

Although California law now considers PTSD for first responders a presumption, it is a “disputable presumption.” That means claims administrators can consider other traumatic events in a firefighter’s life that may play a role in a PTSD case.

“With cumulative trauma, or stress over the course of their entire employment, we need to request more information from the doctor so that we can see it isn’t because they were in the military or they are going through a divorce, etc.,” one claims adjuster told RAND researchers.

“The workers’ comp medical treatments system is a stain upon the soul of the politicians and officials of California.”

RICHARD ELDER, WORKERS’ COMP LAWYER

The complexity of the system wears down the resistance of injured workers, who need a jungle guide to find their way at a time of profound pain and disorientation.

“They can't navigate this on their own, they really can't. They’ve got professional litigators opposing them,” said Richard Elder, a workers’ comp lawyer in Concord who regularly represents state firefighters. “The average claims adjuster on the job for more than a month knows more about the system than the average firefighter. They’ve got lawyers on speed dial. The injured worker is adrift. It’s like a do-it-yourself heart transplant.”

Elder, who has been in practice for 54 years, used to work as an insurance company claims adjuster. The system, he says, has always been adversarial.

“It's against the law for employers to discriminate against a worker who files a psyche claim. But they do discriminate,” said Elder, who said in the past five decades he has pursued about 500 psychiatric claims.

“I just filed a psychiatric claim and the response was ‘give us a list of every medical facility that treated the claimant in the last 10 years,’ ” he said. “The workers’ comp medical treatments system is a stain upon the soul of the politicians and officials of California.”

Diagnosing PTSD is ‘a complicated process’

One day in March, Nelson sat next to his wife, Leticia, in a quiet room in a Nevada City library near their rental home. He was in the grips of a seizure, brought on by retelling his firefighting nightmares to a CalMatters reporter. His hands were clenched and his torso taut. He stuttered, his eyelids fluttering. The episode lasted a few minutes.

During the interview, Nelson was fidgety, his thick fingers constantly worrying the items he had put on the table in front of him. One was a tiny aluminum cylinder containing medication for his seizures, another was a brass medallion, the iconic firefighter symbols of an ax and firehose nozzle stamped on one side and the serenity prayer on the other.

The coin was a kind of talisman, given to him after graduating from a specialized rehab clinic for firefighters, where he was given his daunting medical diagnosis: He suffers from complex PTSD, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures and dissociative identity disorder.

Such anxiety-induced seizures are unusual but not rare, his therapist said, and the totality of Nelson’s mental health issues makes his case unusually severe. Weekly therapy sessions and multiple medications have tempered, but not extinguished, his struggle with crippling anxiety.

Nelson wears a medical alert wrist bracelet intended to give first responders a bare-bones outline of his conditions and which medications to avoid when he is experiencing an anxiety-induced seizure. In his back pocket, he carries, always, a medical card with his list of red flags, so extensive that it unspools like an accordion.

His seizures may occur several times a day. Some last for hours. Nelson’s usually benign aspect changes: His eyes cross, his hands clench into what he calls “spidey fingers.” He stumbles and stutters through sentences and repeats words, often losing his ability to speak at all. At times he drags his head and face along walls. Leticia Nelson describes the seizures as his body undergoing earthquakes.

Retired CalFire firefighter Todd Nelson's emergency medical ID card that he carries with him. Nelson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from trauma experienced during his firefighting career. Nevada City, March 19, 2024. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

First: Nelson's container for storing his medication. Last: The emergency medical ID card that Nelson carries with him. Photos by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

Retired CalFire firefighter Todd Nelson alongside his wife Leticia Nelson in Nevada City on March 19, 2024. Nelson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from trauma experienced during his firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

Nelson alongside his wife, Leticia Nelson, near their Nevada City home. She says it's been agonizing to see him suffer mental health problems related to his job and have to fight the system to get his treatment paid for. “We sacrificed our time with him so that he could help the whole state. And nothing has been there for the family since this happened. Nothing." Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

Nelson’s unusual body movements during a seizure, his inability to respond to questions and his propensity to run away when confronted puts Nelson in a precarious place in airport lines or with law enforcement, where his non-response has been misconstrued as defiance.

Even doctors can misunderstand. Diagnosing and treating PTSD and acute trauma like Nelson’s is notoriously difficult.

“Diagnosing PTSD is a complicated process. Diagnostic criteria are complicated,” said Sidra Goldman-Mellor, a UC Merced psychiatric epidemiologist who studies depression and suicidal behavior. “Your average primary care clinician is probably not willing to go down that road.”

For patients like Nelson, any number of stress-related disorders present themselves and muddy a specific diagnosis that would satisfy a claims adjuster or a workers’ comp review.

“That’s the thing with psychiatric disorders, we don’t have a lot of objective measures for a mental health diagnosis. We don't have blood tests and we don't have MRIs,” Goldman-Mellor said. “They (mental health issues) are harder to recognize, harder to test for and easier to ignore.”

But firefighters cannot move easily through the workers’ comp or medical insurance system if they don’t have a diagnosis. Constantly proving your pain becomes its own trauma.

“He has to prove his world is falling apart,” Leticia Nelson said. “It's hard to explain to someone that you are broken. They look at you, they think that you look fine. They can't see in your brain. They can't see in your mind.”

“That’s the thing with psychiatric disorders, we don’t have a lot of objective measures for a mental health diagnosis. They are harder to recognize, harder to test for and easier to ignore.”

SIDRA GOLDMAN-MELLOR, PSYCHIATRIC EPIDEMIOLOGIST AT UC MERCED

It took four years for Nelson to find the right medical care. One physician’s therapeutic approach was to ask the former firefighter to pray with him.

The problem was much more fundamental than finding a compatible therapist: He could not find one to take his case. Many Cal Fire employees are stationed in rural or remote areas of the state, in communities underserved by health care specialists.

Living in rural Nevada County, Nelson faces a barren mental health desert where it’s difficult to find a competent therapist who might have worked with other first responders and understands the specific challenges of the high-stress job.

“It’s an absolute specialization. There’s not near enough of us,” said Alexander, Nelson’s therapist. (Nelson granted her permission to speak about his case.) “In the larger Sacramento area there are less than a dozen competent providers.”

Todd Nelsen recalls memories of his time as a firefighter during his session at Jennifer Alexander's office in Gold River on April 24, 2024. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Nelson recalls memories of his time as a firefighter during a treatment session. Photo by Cristian Gonzalez for CalMatters

Cal Fire is self-insured and offers medical coverage through private companies. The agency does not manage medical claims or workers’ comp but does have programs to assist employees in finding care.

Rob Wheatley, staff chief of Cal Fire’s Behavioral Health and Wellness Program, told CalMatters in an email that the agency has expanded support for employees who seek help for mental health issues with peer counseling or referrals for treatment. The agency has a staff of 28 assisting about 12,000 employees.

But Wheatley and other Cal Fire officials refused to grant an interview and did not answer CalMatters’ questions about the problems that their employees face with workers’ comp and mental health issues.

“Any denial of a mental health claim is concerning,” Wheatley said in the email.

Can the system be repaired?

The Nelsons have seen the insurance and workers’ comp system from the inside, been batted around by it and, they would say, abandoned by it. Still they have few suggestions to fix it.

They are not alone. Lawyers say that the system is based on how to save money, is too often adversarial and deeply entrenched.

Even the employers who participate in the workers’ comp system say it’s not working well. In a recent survey, more than half of the respondents said the system performs poorly while 42% described the system as challenged but adequate.

“Nobody believes it’s ideal,” said Jerry Azevedo, a spokesman for the Workers’ Compensation Action Network, a coalition of California insurers, employers and agents advocating to improve the system. “Every constituency has complaints.”

Azevedo said California’s workers’ comp system, which has been in place since 1913, is plagued by persistent problems: high costs to operate, huge claim volume, frequent litigation, slow claim resolution and fraud and abusive practices.

“The fundamental challenge we all contend with is complexity. California’s system is arguably the most complex in the nation,” Azevedo said. The good news, he said, is that 86% of workers’ comp claims overall are accepted, according to the California Workers’ Compensation Institute.

It’s easy to get the sense of a general throwing up of hands. The state Commission on Health & Safety & Workers’ Comp dedicates a webpage to tracking workers' comp reforms, but the last entry was in 2012.

Sean Cooper, executive vice president and chief actuary of the Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau of California, said the system is groaning under its own weight — there are a lot of people filing claims and a lot of lawyers on all sides.

Administrative costs are high in California: The cost to deliver $1 of medical benefit from California’s workers' comp system is 46 cents, compared to two cents for Medicare, 19 cents for private group health insurance and 25 cents for the national state median for workers’ comp according to the group’s 2023 report.

One way to fix the inequity is to turn the system on its head, said Cruz of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“There is a disparity about how we treat, respond and react to behavioral health versus physical health,” she said. “Maybe we need to start talking about that disparity in workers’ comp. When you have (a claims) approval rating that is flipped on its backside, that’s an obvious parity issue.”

Legislators, when they turn their gaze to the massive program, chip away at the edges. The law extending the PTSD presumption will be revisited when the state Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation presents its report on claims and denials to the Senate Committee on Labor, Public Employment and Retirement and the Assembly Committee on Insurance, by the end of this year.

Cruz said there is more legislative focus on behavioral health than ever, but there are limits, beginning with which groups carry the most influence. Managed health care companies are powerful advocates of the status quo, she said. “We are David and Goliath when we come up against these folks.”

“So many great people want to do wonderful things and they have big ideas, but it gets chopped down to a Band-Aid once everyone gets what they want,” she said.

‘A slap in the face to all of us’

Leticia Nelson refers to herself, with only slight exaggeration, as her husband’s “service dog.”

She’s the keeper of the couple’s appointment schedule, she’s the chauffeur, the manager of the financial spreadsheet. And it falls to Leticia to devote untold hours on the phone with insurers and medical providers, birddogging bills, late payments and coverage lapses.

She has watched her husband humiliated, scared and angry. Their two adult daughters, also have been treated for PTSD, after witnessing their father’s anxiety and mania, and knowing about his suicide attempts.

At times, Leticia Nelson said, “I’m mad at God.”

Retired CalFire firefighter Todd Nelson walks with his wifein Nevada City on March 19, 2024. Nelson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from trauma experienced during his firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

Retired Cal Fire firefighter Todd Nelson walks with his wife in Nevada City. Nelson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from the trauma experienced during his firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

The Nelsons, lifelong Californians, want to leave the state and its frightening tableau of wildfires. They sold their house, changed their mind about moving and now are financially shut out of the real estate market, especially because of the high cost of fire insurance in the foothills where they live. They are nomads, shuttling between Airbnbs with two large dogs and three cats in tow and their possessions in storage.

Money is tight. Leticia would like to go back to work, but she can’t leave Todd alone.

Nelson gave up fighting the state over a disability claim after his attorney told him that an appeal would cost $50,000 — and he would lose because he didn’t claim a disability when he retired.

“It’s a slap in the face to all of us because we sacrificed as a family,” Leticia Nelson said of Todd’s long career with Cal Fire. “We sacrificed our time with him so that he could help the whole state. And nothing has been there for the family since this happened. Nothing.

“I wish that there's things in place that would guide us that wouldn't be so hard. But it just seems like we hit every, every obstacle possible. We’re struggling. We need help. We need to be seen. We need to be treated like humans and not criminals.”

For his part, Nelson is coming to terms with the devastation his career wrought. Yet, years after retirement, he still listens to an emergency scanner and shows up at fires in his area, wearing his T-shirt, shorts and Birkenstocks. The pull to serve remains strong.

“The crazy thing is I miss my job. I miss it every day. I would do it all over again,” he said wistfully. “I loved the job but I didn't realize the damage being done.”

If you are having suicidal thoughts, you can get help from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by calling 988 or visiting https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org

Chief of California’s OSHA program steps down as agency vacancy rate reaches historic levels "The report also included updates on his recent travels and photos of his dog (which some employees have described as “tone-deaf” amid a staffing crises)"

https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/the-state-worker/article283365483.html#storylink=cpy

BY MAYA MILLER

UPDATED DECEMBER 21, 2023 1:37 PM

Jeff Killip, the current chief of the Division of Occupational Safety and Health, will step down from his position with the Department of Industrial Relations in late January. His resignation comes as the division he leads, which is also known as Cal-OSHA, faces a historic staffing shortage.

A top division chief with the California Department of Industrial Relations will step down from his role next month after only two years in the position. Jeff Killip, the chief of the Division of Occupational Health and Safety (also known as Cal-OSHA), announced his resignation Wednesday night in an email to all Cal-OSHA staff. His final day will be Jan. 19. Killip will return to Olympia, Washington, to take on the role of Executive Director of the Washington State Utilities and Transportation Commission. He told staff that after Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed him chief in January 2022, the move from Washington to the Bay Area has been “harder on our family life than we anticipated.” “Despite adjustments and trouble-shooting possibilities, I could not sufficiently improve our situation,” he wrote in the email obtained by The Bee. “I have strong mixed feelings about the decision despite its clarity.” The resignation comes at what some have characterized as a tumultuous time for Cal-OSHA.

Among the more pressing issues that Killip inherited — and has yet to resolve — is a chronic staffing problem. The entire department lost its hiring authority in 2018 after an audit revealed former DIR director Christine Baker engaged in unfair hiring practices. The department earned back its ability to hire in 2021. But ever since, the human resources team has been hyper vigilant about ensuring every hire is merit-based — a practice that current Director Katie Hagen admittedly told The Bee earlier this year might have “over-corrected” the situation and led to sluggish hiring. Hiring and retention became a central mission of Killip’s during his time as division chief. He encouraged hiring managers to block out one day a week to focus on hiring.

He would send a progress report on hiring every week as part of his regular email blasts to Cal-OSHA staff. The report also included updates on his recent travels and photos of his dog (which some employees have described as “tone-deaf” amid a staffing crises).

Despite his verbal commitment to hiring, the numbers don’t show incredible progress. Killip presented data at a November Cal-OSHA advisory committee meeting that showed a nearly 35% vacancy rate among site safety inspector classifications. The data also showed the attrition rate for those jobs outnumbered external hires for a net loss of 36 people. “I wish it would go faster, but we’re making progress, and we’re definitely encouraged by that,”

Killip said at the November meeting in his remarks about hiring progress. He pointed out that the division has made a number of hires in the legal and consultation departments, as well as the Cal-OSHA administrative team. “We’re flying the plane while we’re building it so we can get more people on board more quickly.” The resignation comes amid an ongoing Sacramento Bee investigation into the consequences that Cal-OSHA’s high vacancy rate poses for workplace safety, the ability to hold employers accountable for serious injuries and deaths, and overall morale within the department. Garrett Brown said the timing of Killip’s resignation was too perfect to not have some connection to the staffing issues and persistently high vacancy rate.

Brown, a former special assistant to past Cal-OSHA Chief Ellen Widess, has been an outspoken advocate for staffing up Cal-OSHA ever since he first retired from the division in 2014 (he returned as a retired annuitant in 2020 to assist with the pandemic workload).

“I think there’s been growing pressure on the agency to do a better job at hiring and reducing the vacancy rates.,” Brown said. “And whatever efforts he’s made in that regard, which I believe are genuine, have not succeeded. “It wouldn’t surprise me that in seeing the writing on the wall — that this has become a political issue no doubt of concern to the governor’s office and certainly to the director of the Department of Industrial Relations.

He might’ve sought an off-ramp back to Washington rather than be a sacrificial lamb for the inability of Cal-OSHA and DIR to hire.”

Killip on Wednesday declined to comment further beyond the remarks in his email. “I am immensely grateful for my privileged time here with Cal/OSHA and super proud of the great work we have done together,” he wrote in the all staff email. “Cal/OSHA and California are amazing.”

Dangerous hollowing out of Cal/OSHA enforcement staff continues-Governor Newsom & Legislature Continue To Allow Destruction of CA OSHA

https://insidecalosha.org

Dear Colleagues:

The latest available data on Cal/OSHA’s field compliance inspector levels documents a dramatic and dangerous hollowing out of the worker protection’s agency capacity to enforce workplace health and safety regulations.

An office-by-office head count of filled and vacant compliance health and safety officer (CSHO) positions as of July 1, 2023 (not released by the Department of Industrial Relations until September 5th) reveals Cal/OSHA has 95 vacant field inspector positions for a vacancy rate of 35%. If the additional fully funded 14 vacant CSHO positions being held in reserve are included, there are 109 vacant CSHO positions for a rate of 38%.

The senior manager positions for Region 3 (San Diego, Santa Ana and San Bernardino) and the Process Safety Management (PSM) unit are vacant.

There are three District Offices without managers – Fresno, Van Nuys, and Santa Ana LETF offices – and four offices without any clerical staff – American Canyon, Los Angeles, Concord PSM Refinery, and Concord PSM Non-refinery units.

There are 10 District Offices that have CSHO vacancies of more than 35% of enforcement personnel:

- San Francisco, 67%

- San Bernardino, 62%

- Bakersfield, 50%

- Long Beach, 50%

- Fremont, 45%

- San Diego, 45%

- Van Nuys, 45%

- Sacramento, 42%

- PSM Refinery unit, 40%

- PSM Non-Refinery unit, 40%

The PSM Refinery unit has only 10 positions – four of which are vacant – leaving only six CSHOs to inspect the state’s 15 operating oil refineries. The PSM unit has no regional manager and Cal/OSHA does not use all the funds generated annually by a fee on the refineries’ production.

Overall, Cal/OSHA’s inspector to worker ratio is 1 inspector to every 110,000 workers in the state. This compares to ratios of 1 to 27,000 in Washington state and 1 to 26,000 in Oregon. Surely the workers of California deserve the same level of protection as workers in Oregon and Washington.

Other notable aspects of the most recent staffing data include:

- There are only 16 field enforcement inspectors at Cal/OSHA that are certified in speaking languages other than English;

- There is a vacancy rate of 32% (12 attorney positions) in the Cal/OSHA Legal Unit which handles employer appeals of citations, rulemaking, and legislative analysis;

- The Consultation unit (which provides free service to employers) has a vacancy rate of 28% in field consultants, and four of the seven Consultation Area Offices do not have an Area Manager.

Despite publicized efforts to fill these Cal/OSHA vacancies by the Department of Industrial Relations, the failure to do so over a period of years now means California cannot effectively protect the health, safety, and lives of the state’s 19 million workers.

Garrett Brown

Workers and health and safety advocates will speak out about the attack on health and safety on the job and the corruption of the workers compensation system as well as the capture of government agencies by employers that are supposed to be protecting workers on the job and injured workers

Saturday July 27 @ 10:00 am - 1:00 pm PDT

FREE

At: ILWU Local 6 – 99 Hegenberger Rd. Oakland

There are less than 200 OSHA inspectors for the 18 million workers of California. The Covid pandemic led to the deaths of many workers at food processing companies like Foster farms and many nursing homes because of a failure to provide PPE and educate the workers. Additionally seriously injured workers face a gauntlet of obstacles getting prompt medical treatment and workers compensation. Many workers say that workers comp has been captured by the employers, insurance companies and a State and Federal administration that is representing this interests rather than workers. Workers from the ILWU and other unions as well as advocates fighting for workers compensation and health and safety will speak out.

They will report on this crisis and how it is destroying workers and their families.

Speakers:

Injured Workers Unite

Rank and File Workers

Desiree Rojas – President, Labor Council For Latin American Advancement Sacramento Chapter, and others

Sponsored by WorkWeek

Additional Media:

Demo Gov Newsom Attacks Labor Reps On OSHA Board-Helping Bosses Injure & Murder Workers

Newsom shakes up workplace safety board that bucked him on heat rules

https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/newsom-california-safety-board-19515018.php

By Jeanne Kuang

June 16, 2024

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed indoor heat protection rule this year.

Jessica Christian/The Chronicle 2022

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed heat protection rule this year.

The shake-up comes less than two weeks before the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board is expected to approve the rule, requiring businesses to shield their indoor workers from the risks of extreme heat. The state spent years developing the proposal, only for its approval to be further delayed in March when Newsom’s administration withdrew its support the day before a scheduled vote over cost concerns.

The two members who were recently reshuffled were among those most outspoken on the administration’s last-minute move, which pushed back the rule so that it has not gone into effect in time for the first of this summer’s heat waves.

ADVERTISEMENT

Article continues below this ad

During the March meeting, board member Laura Stock called the action “completely outrageous” and said it “undermines” the board, while Chairperson Dave Thomas said the administration “set us up.” Thomas suggested taking a largely symbolic vote to pass the rule anyway, in a public rebuke of the administration. His motion passed, unanimously.

Stock said she got a call last Friday from an appointments official in Newsom’s office telling her she was off the board, effective immediately, with no explanation.

“It was very shocking. There was no indication that anything like this was planned,” Stock told CalMatters of the call. “I was simply told the governor decided to move in a different direction.”

More For You

Gov. Newsom halts effort to protect California workers from indoor heat, citing cost

Arjun Kandel makes chicken curry at Himalayan Pizza and Momo Wednesday, Sept. 12, 2018 in San Francisco, Calif.

Newsom offers compromise to protect indoor workers from heat, but some will have to wait

Franky Ho, front to back, co-owner Four Kings, prepares a dish in a wok as Mike Long, grills a Xin Jiang lamb skewer in the kitchen at Four Kings on Monday, February 26, 2024 in San Francisco, Calif.

Newsom also replaced Thomas as chairperson with board member Joseph Alioto, an antitrust attorney, the governor’s office confirmed. Thomas, president of a Northern California construction union, remains a board member. He did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Stock, a researcher and director of the Labor Occupational Health Program at UC Berkeley, held a seat reserved for workplace safety experts on the seven-member board since 2012.

Her latest reappointment was in 2020, and expired last June. It is not uncommon for state board and commission members to serve for months on expired terms before the governor’s office reappoints or replaces them. Two other workplace safety board members — a labor representative and an employers’ representative — are also still serving on terms that expired last June.

Alex Stack, a spokesperson for Newsom, wrote in an email that his office would not “comment further on personnel matters.” No replacement for Stock had been appointed as of Friday.

Stock said she did not want to speculate on the reasons for her removal and said she was proud of her work on the board. “The board passed what I consider groundbreaking, cutting-edge, essential regulations protecting workers from sometimes life-threatening hazards,” she said.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed indoor heat protection rule this year.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has removed one member and demoted the chairperson of a state workplace safety board who criticized his administration’s handling of a proposed indoor heat protection rule this year.

Michael Macor/The Chronicle 2017

But worker advocates said they are concerned about the removals.

Stephen Knight, executive director of the advocacy group Worksafe, praised Stock as “one of the most experienced voices for worker health and safety” and Thomas for leading the board through the COVID-19 pandemic. In those years, the board considered renewals of an emergency rule to reduce transmission of the virus in worksites, amid intense public backlash from proponents of reopening businesses.

“If the governor has a direction or vision for worker health and safety, it’s not one that he’s articulated, and we’re all ears,” Knight said. “We’re concerned about what these surprise removals may mean about the governor’s commitment to worker health and safety, and climate justice.”

Administration officials have said they pulled their support from the indoor heat rule in March after discovering the rule would cost state prisons billions more dollars than the workplace safety agency estimated. But it has so far refused to disclose its cost estimates and denied a CalMatters request for public records relating to the costs.

The rule the board is scheduled to vote on Thursday is an amended version that exempts state prisons.

Jeanne Kuang covers labor, politics and California’s state government for CalMatters, where this article first appeared. Reach her at jeanne [at] calmatters.org.

June 16, 2024

Jeanne Kuang

Labor Supported Gov Newsom Attacks Labor Reps On OSHA Standards Board

by Garrett Brown

The crisis in California’s worker protection agencies has deepened in the last week as Governor Gavin Newsom removed one pro-worker Board member, and demoted the labor representative serving as Chair, of the Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board.

Board member Laura Stock, Director of the Labor Occupational Health Program at UC Berkeley and on the Board for 12 years, was summarily dismissed by the Governor’s Appointments Office on June 7th. Union official Dave Thomas was demoted from Chair and remains on the Board. The new Board chair is attorney Joseph Alioto, who has no known expertise or knowledge of workplace health and safety, but is a longtime political operative appointed to the Board by Newsom earlier this year.

The crimes committed by Stock and Thomas apparently were in opposing Newsom’s efforts to further delay a regulation to protect workers from indoor heat which has been years in the making. The Governor’s Appointments office told Stock that Newsom wanted her off the Board because the Governor “wants to go in a new direction.”

The employer community has applauded the removal of Stock, no doubt raising Newsom’s “business-friendly” status for his future political campaigns.

Meanwhile, the “new direction” in staffing Cal/OSHA’s enforcement inspectorate is more vacancies among field compliance officers. According to the latest available data, on March 1, 2024, Cal/OSHA’s vacancy rate for field compliance inspectors reached 39% with 109 vacancies. If the 11 compliance safety and health officer (CSHO) positions being held in reserve are included in the tally, then Cal/OSHA’s inspector vacancies reach 41% with 120 CSHO vacancies.

The debilitating gaps in workplace health and safety coverage are clearest at the local level. Nineenforcement District Offices have CSHO vacancy rates at or above 40% -- Santa Ana (73%), San Francisco (66%), San Bernardino (64%) and Fremont (64%), American Canyon (55%), Bakersfield (50%) and Long Beach (50%), Sacramento (45%), and Fresno (42%).

Another three District Offices have CSHO vacancy rates between 33% and 40% -- Los Angeles, Oakland, and Foster City. This means that a dozen Cal/OSHA District Offices have crippling vacancies that severely undermine safety protections for California’s 19 million workers.

The California Employment Development Department (EDD) reported the California civilian labor force in March 2024 as 19,346,200 workers. The 162.5 field-available CSHO positions represents an inspector to worker ratio of 1 inspector to 119,053 workers. Cal/OSHA’s inspector to worker ratio of 1 inspector to119,000 workers is much less health protective than Washington State’s ratio of 1 to 26,000, and Oregon’s ratio of 1 to 24,000.

There are also key manager vacancies with no Region III Manager (Los Angeles-Orange County), and no District Managers for the Fresno and Monrovia offices. There are two District Offices – Los Angeles and the Concord PSM – with zero clerical staff, which means that CSHOs must spend time doing administrative work.

There are only 10 field enforcement positions for PSM refinery unit covering the state’s 15 oil refineries, and four of those positions are vacant.

According to the Cal/OSHA’s “Organization Chart,” there are only 15 CSHOs classified as “bilingual,” and Region II (Central Valley) has no bilingual field inspectors.

Cal/OSHA has only six (6) industrial hygienists among field inspectors – with none in Region I (San Francisco), Region IV (Los Angeles), and the PSM unit. Industrial hygienists are needed to conduct “health” inspections to evaluate harmful exposures to hazardous chemicals, noise and heat, ergonomics and repetitive motions. Cal/OSHA has brand new standards to protect workers against airborne silica and lead, as well as heat exposures in a changing climate – but now has only extremely limited capacity to conduct effective industrial hygiene inspections.

Cal/OSHA’s Legal Unit has an attorney vacancy rate of 15% (5 of 34 positions) at a time of increased employer appeals of enforcement citations requiring corrective action to protect workers.

Meanwhile, Cal/OSHA’s “Bureau of Investigation” (BOI) which investigates and refers to county District Attorneys cases that trigger possible criminal charges has only one investigator for the entire state – and five vacancies. The once-feared BOI unit has lost virtually all of its deterrent impact with near-zero referrals for fatal accidents and multiple injury events.

Cal/OSHA’s Consultation Service – which provides free service to employers, especially small employers unfamiliar with workplace health and safety – also has a 50% vacancy rate for field personnel (18 out of 36 positions). As new regulations go into effect, such as the recently enacted lead and silica standards, the Consultation Service will be able to assist far fewer employers.

In recent months there has been damning publicity about the years-long staffing crisis and its impact on workers in California in the Los Angeles Times and Sacramento Bee, journalism websites CalMatters and Capital & Main, and public radio stations like KQED in San Francisco.

Nonetheless, California’s Governor, Labor Secretary, and Director of the Department of Industrial Relations have failed to end the field inspector vacancy crisis and protect California workers from irresponsible employers.

Best, Garrett Brown

Newsom Dismisses Workplace Safety Regulator Ahead of Important Vote

By Farida Jhabvala Romero Jun 12

Save Article

Cook Giovanni Gomez preparing chicken on the grill for food orders in the busy kitchen of the El Pollo Loco restaurant in Agoura Hills on Aug. 18, 2021. (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Gov. Gavin Newsom removed an outspoken occupational safety expert from

a powerful regulatory body that adopts California’s workplace safety rules.

In addition to ending Laura Stock’s term as a member of the Occupational Safety & Health Standards Board, Newsom demoted David Thomas, the former chairperson.

Several worker advocates told KQED they were suspicious of the shakeup with just over a week before the board is scheduled to vote on indoor heat illness prevention rules. They are worried that the board could become less protective of vulnerable workers.

“It’s concerning that a member like Laura Stock, who has so much expertise and is so committed to workplace health and safety, would be removed,” said Tim Shadix, legal director at the Warehouse Worker Resource Center, which is pushing for the indoor heat illness protections.

Newsom’s office confirmed that Stock is no longer on the workplace safety board. Joseph Alioto Jr., the San Francisco trial lawyer Newsom appointed last summer, was named chair. A spokesperson for the governor declined to comment on why

Newsom made the changes or when he’ll make an appointment to fill the vacant seat on the seven-member body.

Sponsored

In an interview with KQED, Stock said the governor’s office told her on June 7 that she was terminated from the board. When she asked for more information, according to Stock, the person only said that Newsom had “decided to go in a different direction.”

“I was shocked and surprised,” said Stock, who directs the Labor Occupational Health Program at UC Berkeley. “There had been no indication that this decision was coming.”

Stock spent 12 years on the board, contributing to the passage of life-saving protections for hazards such as COVID-19, lead poisoning and silica dust from engineered stone that has killed and disabled countertop fabrication workers.

“I was inspired by the many workers who had the courage to come and share their experiences and speak up about what was

needed to protect them on the job,” Stock said.

A representative of a large employer association did not lament Stock’s departure, claiming she often failed to listen to the concerns of member companies about proposed health and safety requirements.

“We as business stakeholders never really felt like Laura had any capacity for dispassionate analysis of the issues laid in front of her,” said the representative, who requested anonymity because they feared reprisal from Stock if she accepted another regulatory post. “She always had a position. You always knew how she’d vote. She never asked any questions of any criticism we would lay out.”

Heat illness protections for indoor workers have been delayed for years. In March, the board was expected to approve new requirements, but the Newsom administration withdrew its support seemingly at the last minute. Facing outrage from workers and their advocates, Stock and Thomas, a labor representative, openly criticized the move and called for a symbolic vote on the regulations. It passed unanimously.

Shadix questioned whether the board changes could be connected to those actions.

“It certainly seems a little bit suspicious and worrying that two of the members who were most outspoken for moving that indoor heat standard are now being demoted and removed,” he said. “We hope that this is not going to impact that being voted on and approved next week. Every summer that goes by without that standard in place, we see more suffering.”

‘Total system breakdown’: California firefighters with PTSD face a workers’ comp nightmare & LaborFest meeting on Injured Workers & OSHA

https://calmatters.org/environment/2024/06/california-firefighers-ptsd-workers-comp/

BY JULIE CART

JUNE 26, 2024

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Retired CalFire firefighter Todd Nelson in Nevada City on March 19, 2024. Nelson suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from trauma experienced during his firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

Retired Cal Fire Captain Todd Nelson, shown in Nevada City, suffers from a severe case of post traumatic stress disorder resulting from his 28-year firefighting career. Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

IN SUMMARY

Even when suicidal, California firefighters struggle to find medical help and navigate the workers’ comp morass to pay for it. A 2021 analysis showed their claims were more likely to involve PTSD — and were denied more often.

Todd Nelson could feel it coming on. And he began to run. He was going dark again, retreating to a place where he would curl into a fetal position with his thumb in his mouth, watching from behind closed eyes as his personal reel of horror unspooled. Sights and sounds from three decades of firefighting cued up — shrieks from behind an impenetrable wall of flame, limbs severed in car accidents and the eyes of the terrified and the dead he was meant to save.

Nelson was running on the Foresthill Bridge, the highest in California, fleeing cops and firefighters after his wife reported that he was suicidal. He hurdled a concrete barrier and straddled the railing of the bridge in the Sierra Nevada foothills, staring down at a large rock 730 feet below. As the rescuers closed in, Nelson leaned precariously over the chasm. His strategy — making the fatal plunge appear accidental, allowing his family to collect his life insurance.

It was not Nelson’s first suicide attempt — the former Cal Fire captain had tried to take his life many times before. But after that 2021 ordeal, which led to an involuntary 72-hour psychiatric hold, something in him shifted. He was ready to admit that he had a problem and seek medical help.

The incident began the firefighter’s arduous, years-long journey toward wellness, threaded through a bureaucratic labyrinth strewn with more obstacles than he’d ever encountered on a California wildfire: finding qualified medical help, battling an insurance company to pay for it and navigating the tangled morass of California’s workers’ comp. All without going broke or returning to his dark place.

No one tracks how many of Cal Fire’s 12,000 firefighters and other employees suffer from mental health problems, but department leaders say post traumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts have become a silent epidemic at the agency responsible for fighting California’s increasingly erratic and destructive wildfires. In an online survey of wildland firefighters nationwide, about a third reported considering suicide and nearly 40% said they had colleagues who had committed suicide; many also reported depression and anxiety.

California’s workers’ comp — which is supposed to help people get medical treatment for workplace illnesses and injuries — can be a nightmare for firefighters and other first responders with PTSD.

Claims filed by firefighters and law enforcement officers are more likely to involve PTSD than claims by the average worker in California — and they have been denied more often than claims for other medical conditions, according to the research institute RAND.

From 2008 to 2019 in California, workers’ comp officials denied PTSD claims filed by firefighters and other first responders at more than twice the rate of their other work-related conditions, such as back injuries and pneumonia, RAND reported. About a quarter of firefighters’ 1,000 PTSD claims were denied, a higher rate than for PTSD claims from other California workers.

Become a CalMatters member today to stay informed, bolster our nonpartisan news and expand knowledge across California.

“It’s a fail-first system. You have to get a broken leg to show you are in need of support. With mental illness, we are constantly having to prove to everybody why we were ill. You have to get to the point of suicide,” said Jessica Cruz, the California chief executive officer of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Jennifer Alexander, Nelson’s therapist, said patients in acute crisis simply don’t have the mental capacity to ride herd on stubborn workers’ comp claims. Alexander said she was once on hold for more than six hours with Cal Fire’s mental health provider attempting to get one of her bills paid, and she has waited years to get paid for treating firefighters.

“People give up. It’s a battle… They are not fully functional,” said Alexander, who for 21 years has specialized in treating first responders with trauma and PTSD and has spent an estimated 25,000 hours treating them. “You are not talking about healthy individuals who can sit on the phone for hours.”