From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

The Problem of Policing: A Primer, Part II

How slave patrols shaped modern policing and sparked the prison-industrial complex.

Miss part I? Read it HERE

To start, let’s be absolutely clear about one thing: police do not prevent crime. If this thought has never occurred to our readers, it is because many of us have been taught, from childhood, that police are helpers and exist to protect their communities. According to Phillip Bump, a columnist for the Washington Post, while police spending has skyrocketed over the last two decades, crime has not fallen in a correlating manner (Bump, 2020).

For example, in 1960, total national spending on police was around $2 billion, and violent crimes were holding steady at 161 per 100,000 citizens. By 1980, our country was spending $14.6 billion on policing, but violent crimes had risen to 597 per 100,000 citizens. By the time 2018 rolled around, we were spending $137 billion on policing and violent crime was still holding steady at 381 per 100,000 people (Bump, 2020).

But perhaps it isn’t just spending that will get our crime rates, especially our violent crime rates down. Maybe we are looking at the wrong thing. Spending doesn’t necessarily equate to more police officers, better training, or better response times. Sometimes spending is just that: spending. We already saw in the previous chapter that police departments will often make frivolous purchases on military gear that mainly collects dust. Perhaps police departments are simply spending on the wrong things and we can correct it through reforms.

Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case, for a variety of reasons. Let’s start with the answer that so many reformers tend to give; hiring more officers to flood high crime areas and bring the rates down. However, “research also indicates that the number of officers in a given area at a particular time has virtually no impact on crime rates, victimization rates, or the public’s satisfaction with the police” (Barkan & Bryjak, 2013). Couple this with the fact that for two decades now, the number of police officers per 1,000 civilians has been steadily decreasing; but so has crime (Weichselbaum & Thomas, 2019). In other words, the liberal reformist ideology of becoming a safer community through a more saturated police force, is thoroughly debunked.

On top of this, the United States Supreme Court very famously ruled, multiple times, that police have no actual legal obligation to protect this country’s citizenry.

In the 1981 case Warren v. District of Columbia, the D.C. Court of Appeals held that police have a general "public duty," but that "no specific legal duty exists" unless there is a special relationship between an officer and an individual, such as a person in custody. The U.S. Supreme Court has also ruled that police have no specific obligation to protect. In its 1989 decision in DeShaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services, the justices ruled that a social services department had no duty to protect a young boy from his abusive father. In 2005's Castle Rock v. Gonzales, a woman sued the police for failing to protect her from her husband after he violated a restraining order and abducted and killed their three children. Justices said the police had no such duty (Dahl, 2022).

Few cases have made this more clear than the disaster that was Uvalde. When a gunman entered an elementary school and opened fire, killing several children, the Uvalde Police - who had just months prior made social media posts bragging about their new military equipment - cowered in fear and refused to engage with the gunman. The only thing police did that could have been said to be within the scope of their job was to arrest parents who attempted to enter the school to save their children. One parent who was initially handcuffed, managed to talk her way out of custody and rescued her children. Instead of being crowned a hero, she faced repeated police harassment for her actions instead (Lopez, 2022).

In his book Police for the Future David Bayley expresses that police not preventing crime is one of the “best kept secrets” and that “experts know it, the police know it, and the public does not know it” (Bayley, 1994). Other experts claim that police are “outgunned by circumstance” and have laid out the root causes of crime as being “a product of conditions well beyond the scope of police resources and authority [such as] the distribution of income and wealth, poverty and unemployment, the racial and ethnic composition of an area… and a host of more subtle psychological, sociocultural, and economic variables” (Barkan & Bryjak, 2013). In other words, the material conditions created by capitalism are the ultimate causes of crime; though readers would be hard-pressed to find a crime and justice expert willing to use that wording. And what can a police officer do about material conditions, even if they were made fully aware of them? Because such things are removed from the scope of their duties, they cannot use their position to better circumstances on any meaningful level, and thus crime continues as it always has: unimpeded by our systems of policing.

So then, what is the purpose of the police? Why bother having a police force at all if they make no impact on crime and if they have no legal obligation to protect the public?

The answer itself is actually quite simple, but the context surrounding the answer is not. Police exist in order to uphold that status quo and to protect property. Their function is done, completely devoid of morality or intellectual reasoning; their duties carried out regardless of their harm. In order for our simple answer to make any sense, we need to take an even deeper step into the history surrounding our contemporary system of policing, and how and why it is so harmful to the average citizen.

Slave Patrols and the Prison Industry

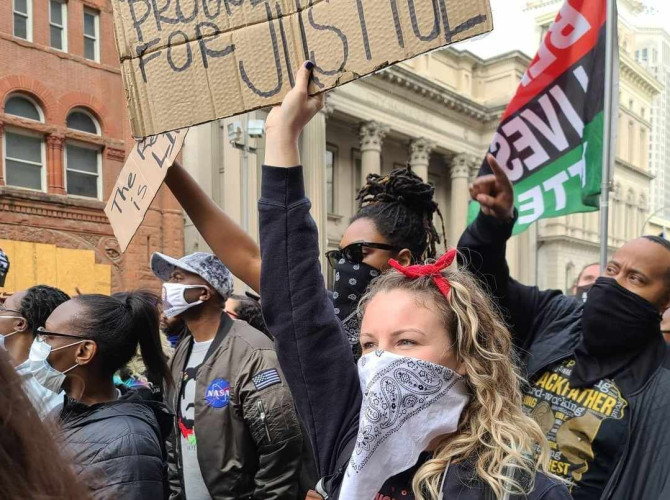

During the 2020 uprisings, it became more common knowledge that policing had begun as slave patrols. And while this is mostly true, there were other parts of society that used systems of security that eventually were absorbed, along with slave patrols, into the form of policing we are used to seeing.

In many ways, the southern United States has always been the home to political shifts, changes, and upheavals that ultimately affect the entire country. While the capital-driven slave trade is what often comes to mind as the legacy of the southern states, there is more. But that is something we will spend time with further on in the book. For now, let’s look at how modern policing was born out of, and shaped by the brutality of slavery.

The first slave patrol was formed in South Carolina in 1704. Most often, names of local landowners were assembled and given the responsibilities of the slave patrol, which were mainly: “(1) to chase down, apprehend, and return to their owners, runaway slaves; (2) to provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts; and, (3) to maintain a form of discipline for slave-workers who were subject to summary justice, outside the law” (Potter, 2013).

The first point in that list is what slave patrols were most famous for. We know stories of black suffering and black resistance when it comes to the American slave system. Most people who have passed through the education system in the United States have at least heard of people like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass. We know that something called the underground railroad existed and that it was a series of connected revolutionaries willing to smuggle escaped enslaved folks. What we mention in those stories, but rarely get any detail on, are the “slave catchers”. They exist in the background of these stories, widely ignored as a thing of the past that only existed for a short time. What people may not realize is that slave patrols were active from 1704 and all the way through emancipation; more than 150 years (Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing, n.d.).

An easy place to look for slave patrols in black culture today is to look at the history of black ghost stories. Many contemporary ghost stories rely on some sort of tragedy, or a place of great pain; a lost love, a murdered family, a battlefield, or a warning from beyond. These are all typically white American ghost stories. And like fairytales of old, they often have some sort of message or warning, telling children and adults alike to watch out, be careful, and be kind to others. However, black ghost stories are different. Black ghost stories, especially during the reconstruction era and pre-emancipation, would serve as a very real, very deadly warning. If there was a scary story about a ghostly stagecoach that would come and steal children away in the night, well, then there was probably a very real stagecoach manned by slave patrols that would come and steal away black children to drag them into the bonds of slavery. Black ghost stories were born out of fear of what the white man would do if he found an enslaved person who had escaped; or what they might do even to a freed person (Dickey, 2016). These stories have been passed down through generations, always changing with the times. But there was true fear behind those stories; a fear that mad parents tell ghost stories to keep their children nearby and safe. Because despite the emancipation proclamation, the danger that haunted black folks was still very real.

Though the system of slavery found itself gutted in the mid 1800s doesn’t mean that slave patrols ended. Anyone familiar with the reconstruction era of the post-civil war south will recognize that the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was founded by former enslavers, overseers, and slave catchers, and it was a very active organization. The KKK took up the mantle of vigilante and began its campaign of organized terror. Prior to reconstruction, slave patrols often took this job on themselves. Because slave patrolmen were sworn in, it was seen as their civic duty to terrorize the enslaved folks all throughout the south, so it is easy to see how so many former patrolmen would wind up in the KKK and other “vigilante” terror units (Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing, n.d.).

Wealthy landowners in the south were almost always on edge in regards to a slave revolt or an uprising. Though there were many instances of black resistance and rebellions, such an organized, massive upheaval spreading across the southern states that was so feared never did quite show. A major reason? The terror of the slave patrols.

A slave patrol didn’t exist just to “return” enslaved folks who fled slavery. A slave patrol also existed to monitor and gather intelligence on those who were enslaved. Their goal was to uncover the networks of the underground railroad, and preemptively stop any sort of open rebellions that might be brewing. They were brutal and cruel and had almost free reign over any enslaved individual within their jurisdiction. While an overseer was privately employed to brutalize those who were enslaved, a slave patrolman had a legal responsibility to do so. The breaking apart of families, the whippings, the beatings, the dog attacks, the deprivation of food and water; all of it was done in the name of the law, gifting slave patrolmen a clear conscience, knowing they had simply been doing what society deemed correct by enforcing the law (Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing, n.d.).

But it wasn’t just the southern states in which such patrols operated. Even the northern states had slave patrols. Due to the Fugitive Slave Laws passed by congress, slave patrols were able to operate in all of the United States and its territories. In other words, even if an enslaved person made it to the northern states where slavery was illegal, they could still be arrested and forced back into slavery once again (Kappeler, 2014). In northern states, a black person could even be born free, captured by slave patrols, and forced into slavery via lies and underhanded dealings between plantation owners and the patrolmen (Elliott & Hughes, 2019). And while such incidents were illegal, there was little to no legal recourse for those who were victims of such horrible, systemic oppression.

A reader might be wondering what any of this has to do with modern day policing. Weren’t slavery and reconstruction a long time ago? Police today have none of the “civic responsibilities” of capturing and returning enslaved folks.

But a few things have stuck around since the time of reconstruction; a time when it is generally accepted that most slave patrols evolved into municipal police departments (Potter, 2013). In 2015, the Department of Justice investigated the Ferguson, Missouri Police Department to better understand the conflicts between police and black residents following the killing of Michael Brown by officer Darren Wilson. They discovered, among other things, that the Ferguson Police Department was using K-9 units overwhelmingly on black folks residing within the city limits. The dog attacks were used in a variety of situations, most of which occurred when there was no danger to the lives of police officers or nearby civilians. Instead, the dogs were simply turned loose on people as a tool of fear and oppression; much like dogs and hounds were used in slave patrols. In fact, many people may not realize that all law enforcement K-9 units can trace their lineage directly back to slave patrols and the campaign of terror they unleashed on innocent black families who were trying to live freely. Unfortunately, according to the Department of Justice, such attitudes and methods were still ever present in Ferugson, with no indication that anything was ever going to be done to improve the situation (Spruill, 2016).

The Department of Justice went on to find that it wasn’t just police dogs that were terrorizing the black community in Ferguson. Instead, there was evidence of systemic oppression and over-policing of the black communities in the city. “The history of police work in the South grows out of this early fascination, by white patrollers, with what African American slaves were doing. Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating black slaves” (Hadden, 2003). Because policing came from the very practices of surveilling, monitoring, capturing, and punishing black folks, it has been nigh-impossible to divorce all of the racial prejudices police work was founded upon from today’s police practices.

Unfortunately, such practices are laid bare for all to see in our modern prison-industrial complex. The 2016 documentary 13th opens with former President Obama repeating the oft-cited statistic that America only contains 5 percent of the world’s population, but 25 percent of the world’s prison population (DuVernay, 2016). While such a statistic is shocking, it is also, unfortunately, common knowledge among minority and poorer communities, which bear the brunt of this excessive cycle of arresting and re-arresting. What the documentary 13th awoke many individuals to is the fact that slavery has never been fully outlawed in the United States. The 13th Amendment allows for slavery to be used as punishment for a crime. This meant that immediately during the reconstruction era, federal, state, and local politicians started to pass laws to specifically target the newly emancipated black communities.

Since that time, our prison population has continued to run high and is reflective of how we police in the US; 32% of inmates are black (Prisons Report Series: Preliminary Data Release | Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2023) despite only making up roughly 12% of the population of the United States (Black/African American Health | Office of Minority Health, n.d.). From the very inception of the great emancipation, bad actors have been working to re-enslave the black population via policing and prison systems. And much like the enslaved of the southern plantations, modern day prisoners are treated with similar disdain and cruelty. The poor treatment is only amplified by prison privatization, which seeks to maximize profits.

Profits are maximized by extracting from the prisoners. This occurs through overcrowding and understaffing (Moore, 2017), denying inmates vital healthcare (Segura, 2013), providing poor quality food (Fassler & Brown, 2017), and several other methods. While the aforementioned list highlights some of the degradation suffered by prisoners, it fails to include several more humiliations suffered by our incarcerated brothers and sisters, such as: sexual violence (Struckman-Johnson & Struckman-Johnson, 2000), physical violence, and degradation.

So, we have learned that much of contemporary policing was born out of slave-patrolling for the explicit purpose of continuing to enslave black Americans. Every year, billions of dollars worth of profit is extracted from prison labor. Slavery was never abolished, it just changed its face; and modern police are all too happy to be that face to the public.

References

Barkan, S. E., & Bryjak, G. J. (2013). Myths and Realities of Crime and Justice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Bayley, D. H. (1994). Police for the future. Oxford University Press.

Black/African American Health | Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Office of Minority Health. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/blackafrican-american-health

Bump, P. (2020, June 7). Over the past 60 years, more spending on police hasn’t necessarily meant less crime. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/06/07/over-past-60-years-more-spending-police-hasnt-necessarily-meant-less-crime/?fbclid=IwAR2zllGp7PZvAWLdip1R9BY_4DjTD2lNE89CA_UIOg2uW0bNGw9l_of3kVA

Dahl, R. (2022, June 14). Do the Police Have an Obligation to Protect You? FindLaw. Retrieved February 16, 2024, from https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/law-and-life/do-the-police-have-an-obligation-to-protect-you/

Dickey, C. (2016). Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places. Viking.

DuVernay, A. (Director). (2016). 13th [Film]. Kandoo Films.

Elliott, M., & Hughes, J. (2019, August 19). A Brief History of Slavery That You Didn't Learn in School (Published 2019). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html

Fassler, J., & Brown, C. (2017, December 27). Prison Food Is Making U.S. Inmates Disproportionately Sick. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/12/prison-food-sickness-america/549179/

Hadden, S. E. (2003). Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Harvard University Press.

Kappeler, V. E. (2014, January 7). A Brief History of Slavery and the Origins of American Policing. EKU Online. Retrieved February 21, 2024, from https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/brief-history-slavery-and-origins-american-policing/?fbclid=IwAR3vPvyQO3gAvlH8TIvZrn4SDEOJ6KpqEmAdmBfa4QP-u6p_42mJyuTqMy4

Lopez, R. (2022, July 6). Uvalde Texas mom says police are harassing her. WFAA. https://www.wfaa.com/article/news/special-reports/uvalde-school-shooting/uvalde-mom-says-police-are-harassing-her-for-speaking-out/287-25084f74-f3f4-49e9-b68b-b945c2f34df3

Moore, S. (2017, November 9). California Prisons Must Cut Inmate Population. The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/05/us/05calif.html?pagewanted=print

Potter, G. (2013, June 25). The History of Policing in the United States, Part 1. EKU Online.

Retrieved February 21, 2024, from https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/the-history-of-policing-in-the-united-states-part-1/

Prisons Report Series: Preliminary Data Release | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2023, September 20). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisons-report-series-preliminary-data-release

Segura, L. (2013, October 1). With 2.3 Million People Incarcerated in the US, Prisons Are Big Business. The Nation. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/prison-profiteers/

Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing. (n.d.). National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. Retrieved February 21, 2024, from https://nleomf.org/slave-patrols-an-early-form-of-american-policing/

Spruill, L. H. (2016, Summer). Slave Patrols, “Packs of Negro Dogs” and and Policing Black Communities. Phylon, 53(1), 42-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/phylon1960.53.1.42?read-now=1&seq=1&fbclid=IwAR0wLgqQceNfU5w3Ret8X-J6r3GeHW9GgTHmkU46Fxa4psjCL7OnimQ2M-0

Struckman-Johnson, C., & Struckman-Johnson, D. (2000, December 4). Sexual Coercion Rates in Seven Midwestern Prison Facilities for Men. SPR. http://www.spr.org/pdf/struckman.pdf

Weichselbaum, S., & Thomas, W. C. (2019, February 12). More cops. Is it the answer to fighting crime? USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2019/02/13/marshall-project-more-cops-dont-mean-less-crime-experts-say/2818056002/?fbclid=IwAR1h4n8XBSDx_1k0cl4Huu-vhzaionN5jdbT6edRK5WHXDY7VLRA9mjZLVM

To start, let’s be absolutely clear about one thing: police do not prevent crime. If this thought has never occurred to our readers, it is because many of us have been taught, from childhood, that police are helpers and exist to protect their communities. According to Phillip Bump, a columnist for the Washington Post, while police spending has skyrocketed over the last two decades, crime has not fallen in a correlating manner (Bump, 2020).

For example, in 1960, total national spending on police was around $2 billion, and violent crimes were holding steady at 161 per 100,000 citizens. By 1980, our country was spending $14.6 billion on policing, but violent crimes had risen to 597 per 100,000 citizens. By the time 2018 rolled around, we were spending $137 billion on policing and violent crime was still holding steady at 381 per 100,000 people (Bump, 2020).

But perhaps it isn’t just spending that will get our crime rates, especially our violent crime rates down. Maybe we are looking at the wrong thing. Spending doesn’t necessarily equate to more police officers, better training, or better response times. Sometimes spending is just that: spending. We already saw in the previous chapter that police departments will often make frivolous purchases on military gear that mainly collects dust. Perhaps police departments are simply spending on the wrong things and we can correct it through reforms.

Unfortunately, this does not seem to be the case, for a variety of reasons. Let’s start with the answer that so many reformers tend to give; hiring more officers to flood high crime areas and bring the rates down. However, “research also indicates that the number of officers in a given area at a particular time has virtually no impact on crime rates, victimization rates, or the public’s satisfaction with the police” (Barkan & Bryjak, 2013). Couple this with the fact that for two decades now, the number of police officers per 1,000 civilians has been steadily decreasing; but so has crime (Weichselbaum & Thomas, 2019). In other words, the liberal reformist ideology of becoming a safer community through a more saturated police force, is thoroughly debunked.

On top of this, the United States Supreme Court very famously ruled, multiple times, that police have no actual legal obligation to protect this country’s citizenry.

In the 1981 case Warren v. District of Columbia, the D.C. Court of Appeals held that police have a general "public duty," but that "no specific legal duty exists" unless there is a special relationship between an officer and an individual, such as a person in custody. The U.S. Supreme Court has also ruled that police have no specific obligation to protect. In its 1989 decision in DeShaney v. Winnebago County Department of Social Services, the justices ruled that a social services department had no duty to protect a young boy from his abusive father. In 2005's Castle Rock v. Gonzales, a woman sued the police for failing to protect her from her husband after he violated a restraining order and abducted and killed their three children. Justices said the police had no such duty (Dahl, 2022).

Few cases have made this more clear than the disaster that was Uvalde. When a gunman entered an elementary school and opened fire, killing several children, the Uvalde Police - who had just months prior made social media posts bragging about their new military equipment - cowered in fear and refused to engage with the gunman. The only thing police did that could have been said to be within the scope of their job was to arrest parents who attempted to enter the school to save their children. One parent who was initially handcuffed, managed to talk her way out of custody and rescued her children. Instead of being crowned a hero, she faced repeated police harassment for her actions instead (Lopez, 2022).

In his book Police for the Future David Bayley expresses that police not preventing crime is one of the “best kept secrets” and that “experts know it, the police know it, and the public does not know it” (Bayley, 1994). Other experts claim that police are “outgunned by circumstance” and have laid out the root causes of crime as being “a product of conditions well beyond the scope of police resources and authority [such as] the distribution of income and wealth, poverty and unemployment, the racial and ethnic composition of an area… and a host of more subtle psychological, sociocultural, and economic variables” (Barkan & Bryjak, 2013). In other words, the material conditions created by capitalism are the ultimate causes of crime; though readers would be hard-pressed to find a crime and justice expert willing to use that wording. And what can a police officer do about material conditions, even if they were made fully aware of them? Because such things are removed from the scope of their duties, they cannot use their position to better circumstances on any meaningful level, and thus crime continues as it always has: unimpeded by our systems of policing.

So then, what is the purpose of the police? Why bother having a police force at all if they make no impact on crime and if they have no legal obligation to protect the public?

The answer itself is actually quite simple, but the context surrounding the answer is not. Police exist in order to uphold that status quo and to protect property. Their function is done, completely devoid of morality or intellectual reasoning; their duties carried out regardless of their harm. In order for our simple answer to make any sense, we need to take an even deeper step into the history surrounding our contemporary system of policing, and how and why it is so harmful to the average citizen.

Slave Patrols and the Prison Industry

During the 2020 uprisings, it became more common knowledge that policing had begun as slave patrols. And while this is mostly true, there were other parts of society that used systems of security that eventually were absorbed, along with slave patrols, into the form of policing we are used to seeing.

In many ways, the southern United States has always been the home to political shifts, changes, and upheavals that ultimately affect the entire country. While the capital-driven slave trade is what often comes to mind as the legacy of the southern states, there is more. But that is something we will spend time with further on in the book. For now, let’s look at how modern policing was born out of, and shaped by the brutality of slavery.

The first slave patrol was formed in South Carolina in 1704. Most often, names of local landowners were assembled and given the responsibilities of the slave patrol, which were mainly: “(1) to chase down, apprehend, and return to their owners, runaway slaves; (2) to provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts; and, (3) to maintain a form of discipline for slave-workers who were subject to summary justice, outside the law” (Potter, 2013).

The first point in that list is what slave patrols were most famous for. We know stories of black suffering and black resistance when it comes to the American slave system. Most people who have passed through the education system in the United States have at least heard of people like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass. We know that something called the underground railroad existed and that it was a series of connected revolutionaries willing to smuggle escaped enslaved folks. What we mention in those stories, but rarely get any detail on, are the “slave catchers”. They exist in the background of these stories, widely ignored as a thing of the past that only existed for a short time. What people may not realize is that slave patrols were active from 1704 and all the way through emancipation; more than 150 years (Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing, n.d.).

An easy place to look for slave patrols in black culture today is to look at the history of black ghost stories. Many contemporary ghost stories rely on some sort of tragedy, or a place of great pain; a lost love, a murdered family, a battlefield, or a warning from beyond. These are all typically white American ghost stories. And like fairytales of old, they often have some sort of message or warning, telling children and adults alike to watch out, be careful, and be kind to others. However, black ghost stories are different. Black ghost stories, especially during the reconstruction era and pre-emancipation, would serve as a very real, very deadly warning. If there was a scary story about a ghostly stagecoach that would come and steal children away in the night, well, then there was probably a very real stagecoach manned by slave patrols that would come and steal away black children to drag them into the bonds of slavery. Black ghost stories were born out of fear of what the white man would do if he found an enslaved person who had escaped; or what they might do even to a freed person (Dickey, 2016). These stories have been passed down through generations, always changing with the times. But there was true fear behind those stories; a fear that mad parents tell ghost stories to keep their children nearby and safe. Because despite the emancipation proclamation, the danger that haunted black folks was still very real.

Though the system of slavery found itself gutted in the mid 1800s doesn’t mean that slave patrols ended. Anyone familiar with the reconstruction era of the post-civil war south will recognize that the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was founded by former enslavers, overseers, and slave catchers, and it was a very active organization. The KKK took up the mantle of vigilante and began its campaign of organized terror. Prior to reconstruction, slave patrols often took this job on themselves. Because slave patrolmen were sworn in, it was seen as their civic duty to terrorize the enslaved folks all throughout the south, so it is easy to see how so many former patrolmen would wind up in the KKK and other “vigilante” terror units (Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing, n.d.).

Wealthy landowners in the south were almost always on edge in regards to a slave revolt or an uprising. Though there were many instances of black resistance and rebellions, such an organized, massive upheaval spreading across the southern states that was so feared never did quite show. A major reason? The terror of the slave patrols.

A slave patrol didn’t exist just to “return” enslaved folks who fled slavery. A slave patrol also existed to monitor and gather intelligence on those who were enslaved. Their goal was to uncover the networks of the underground railroad, and preemptively stop any sort of open rebellions that might be brewing. They were brutal and cruel and had almost free reign over any enslaved individual within their jurisdiction. While an overseer was privately employed to brutalize those who were enslaved, a slave patrolman had a legal responsibility to do so. The breaking apart of families, the whippings, the beatings, the dog attacks, the deprivation of food and water; all of it was done in the name of the law, gifting slave patrolmen a clear conscience, knowing they had simply been doing what society deemed correct by enforcing the law (Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing, n.d.).

But it wasn’t just the southern states in which such patrols operated. Even the northern states had slave patrols. Due to the Fugitive Slave Laws passed by congress, slave patrols were able to operate in all of the United States and its territories. In other words, even if an enslaved person made it to the northern states where slavery was illegal, they could still be arrested and forced back into slavery once again (Kappeler, 2014). In northern states, a black person could even be born free, captured by slave patrols, and forced into slavery via lies and underhanded dealings between plantation owners and the patrolmen (Elliott & Hughes, 2019). And while such incidents were illegal, there was little to no legal recourse for those who were victims of such horrible, systemic oppression.

A reader might be wondering what any of this has to do with modern day policing. Weren’t slavery and reconstruction a long time ago? Police today have none of the “civic responsibilities” of capturing and returning enslaved folks.

But a few things have stuck around since the time of reconstruction; a time when it is generally accepted that most slave patrols evolved into municipal police departments (Potter, 2013). In 2015, the Department of Justice investigated the Ferguson, Missouri Police Department to better understand the conflicts between police and black residents following the killing of Michael Brown by officer Darren Wilson. They discovered, among other things, that the Ferguson Police Department was using K-9 units overwhelmingly on black folks residing within the city limits. The dog attacks were used in a variety of situations, most of which occurred when there was no danger to the lives of police officers or nearby civilians. Instead, the dogs were simply turned loose on people as a tool of fear and oppression; much like dogs and hounds were used in slave patrols. In fact, many people may not realize that all law enforcement K-9 units can trace their lineage directly back to slave patrols and the campaign of terror they unleashed on innocent black families who were trying to live freely. Unfortunately, according to the Department of Justice, such attitudes and methods were still ever present in Ferugson, with no indication that anything was ever going to be done to improve the situation (Spruill, 2016).

The Department of Justice went on to find that it wasn’t just police dogs that were terrorizing the black community in Ferguson. Instead, there was evidence of systemic oppression and over-policing of the black communities in the city. “The history of police work in the South grows out of this early fascination, by white patrollers, with what African American slaves were doing. Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating black slaves” (Hadden, 2003). Because policing came from the very practices of surveilling, monitoring, capturing, and punishing black folks, it has been nigh-impossible to divorce all of the racial prejudices police work was founded upon from today’s police practices.

Unfortunately, such practices are laid bare for all to see in our modern prison-industrial complex. The 2016 documentary 13th opens with former President Obama repeating the oft-cited statistic that America only contains 5 percent of the world’s population, but 25 percent of the world’s prison population (DuVernay, 2016). While such a statistic is shocking, it is also, unfortunately, common knowledge among minority and poorer communities, which bear the brunt of this excessive cycle of arresting and re-arresting. What the documentary 13th awoke many individuals to is the fact that slavery has never been fully outlawed in the United States. The 13th Amendment allows for slavery to be used as punishment for a crime. This meant that immediately during the reconstruction era, federal, state, and local politicians started to pass laws to specifically target the newly emancipated black communities.

Since that time, our prison population has continued to run high and is reflective of how we police in the US; 32% of inmates are black (Prisons Report Series: Preliminary Data Release | Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2023) despite only making up roughly 12% of the population of the United States (Black/African American Health | Office of Minority Health, n.d.). From the very inception of the great emancipation, bad actors have been working to re-enslave the black population via policing and prison systems. And much like the enslaved of the southern plantations, modern day prisoners are treated with similar disdain and cruelty. The poor treatment is only amplified by prison privatization, which seeks to maximize profits.

Profits are maximized by extracting from the prisoners. This occurs through overcrowding and understaffing (Moore, 2017), denying inmates vital healthcare (Segura, 2013), providing poor quality food (Fassler & Brown, 2017), and several other methods. While the aforementioned list highlights some of the degradation suffered by prisoners, it fails to include several more humiliations suffered by our incarcerated brothers and sisters, such as: sexual violence (Struckman-Johnson & Struckman-Johnson, 2000), physical violence, and degradation.

So, we have learned that much of contemporary policing was born out of slave-patrolling for the explicit purpose of continuing to enslave black Americans. Every year, billions of dollars worth of profit is extracted from prison labor. Slavery was never abolished, it just changed its face; and modern police are all too happy to be that face to the public.

References

Barkan, S. E., & Bryjak, G. J. (2013). Myths and Realities of Crime and Justice. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Bayley, D. H. (1994). Police for the future. Oxford University Press.

Black/African American Health | Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Office of Minority Health. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/blackafrican-american-health

Bump, P. (2020, June 7). Over the past 60 years, more spending on police hasn’t necessarily meant less crime. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/06/07/over-past-60-years-more-spending-police-hasnt-necessarily-meant-less-crime/?fbclid=IwAR2zllGp7PZvAWLdip1R9BY_4DjTD2lNE89CA_UIOg2uW0bNGw9l_of3kVA

Dahl, R. (2022, June 14). Do the Police Have an Obligation to Protect You? FindLaw. Retrieved February 16, 2024, from https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/law-and-life/do-the-police-have-an-obligation-to-protect-you/

Dickey, C. (2016). Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places. Viking.

DuVernay, A. (Director). (2016). 13th [Film]. Kandoo Films.

Elliott, M., & Hughes, J. (2019, August 19). A Brief History of Slavery That You Didn't Learn in School (Published 2019). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html

Fassler, J., & Brown, C. (2017, December 27). Prison Food Is Making U.S. Inmates Disproportionately Sick. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2017/12/prison-food-sickness-america/549179/

Hadden, S. E. (2003). Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Harvard University Press.

Kappeler, V. E. (2014, January 7). A Brief History of Slavery and the Origins of American Policing. EKU Online. Retrieved February 21, 2024, from https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/brief-history-slavery-and-origins-american-policing/?fbclid=IwAR3vPvyQO3gAvlH8TIvZrn4SDEOJ6KpqEmAdmBfa4QP-u6p_42mJyuTqMy4

Lopez, R. (2022, July 6). Uvalde Texas mom says police are harassing her. WFAA. https://www.wfaa.com/article/news/special-reports/uvalde-school-shooting/uvalde-mom-says-police-are-harassing-her-for-speaking-out/287-25084f74-f3f4-49e9-b68b-b945c2f34df3

Moore, S. (2017, November 9). California Prisons Must Cut Inmate Population. The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/05/us/05calif.html?pagewanted=print

Potter, G. (2013, June 25). The History of Policing in the United States, Part 1. EKU Online.

Retrieved February 21, 2024, from https://ekuonline.eku.edu/blog/police-studies/the-history-of-policing-in-the-united-states-part-1/

Prisons Report Series: Preliminary Data Release | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2023, September 20). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisons-report-series-preliminary-data-release

Segura, L. (2013, October 1). With 2.3 Million People Incarcerated in the US, Prisons Are Big Business. The Nation. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/prison-profiteers/

Slave Patrols: An Early Form of American Policing. (n.d.). National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund. Retrieved February 21, 2024, from https://nleomf.org/slave-patrols-an-early-form-of-american-policing/

Spruill, L. H. (2016, Summer). Slave Patrols, “Packs of Negro Dogs” and and Policing Black Communities. Phylon, 53(1), 42-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/phylon1960.53.1.42?read-now=1&seq=1&fbclid=IwAR0wLgqQceNfU5w3Ret8X-J6r3GeHW9GgTHmkU46Fxa4psjCL7OnimQ2M-0

Struckman-Johnson, C., & Struckman-Johnson, D. (2000, December 4). Sexual Coercion Rates in Seven Midwestern Prison Facilities for Men. SPR. http://www.spr.org/pdf/struckman.pdf

Weichselbaum, S., & Thomas, W. C. (2019, February 12). More cops. Is it the answer to fighting crime? USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2019/02/13/marshall-project-more-cops-dont-mean-less-crime-experts-say/2818056002/?fbclid=IwAR1h4n8XBSDx_1k0cl4Huu-vhzaionN5jdbT6edRK5WHXDY7VLRA9mjZLVM

For more information:

https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2024/04/...

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network