From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Fruit Festivals - CA Black Agriculture Women's Fundraising - Political Activism

Early California Black Churches played a central role not only in the Colored Convention Movement but in Black women’s fundraising and organizing efforts in general. By holding events like the “Fruit Festival,” as well as picnics and fairs, Black women raised funds to build, buy, and sustain churches. Once such churches were established, they also served as channels through which Black women organized and participated in philanthropy and political activism involving fundraising.

In addition to participating in the labor force in various ways, Black women in California contributed to conventions and the general political advancement of African Americans by fundraising and community organizing.

Black women worked as seamstresses, hairdressers, maids, cooks, teachers, and boarding house owners, among other forms of labor.[1]

There were various legal and social structures in place that served to hinder women’s involvement in the work force; however, the reality was that many Black women did not have the financial option of not working and were thus able to find ways of earning income.[2]

This did not mean that Black women had access to political power, even within the conventions and the movement for Black equality. Women were often barred or discouraged from participating.[3] Thus, they found ways to contribute to the cause in their own way, on their own time: fundraising and community organizing.

Within the 1856 Sacramento Convention minutes, there are two references to women’s fundraising. A group of women from Placerville, in El Dorado County, raised $146, with the intention of supporting the State Executive Committee that was fighting to legalize Black testimony in court.[4]

A group of women from San Francisco also formed a Mirror Association to support the Black newspaper, Mirror of the Times, at a time when it was lacking funding. This fundraising effort is especially significant due of the importance of the Black press to the convention movement. The fact that Black women rallied around the Mirror to provide funding shows their dedication to the specific causes of the convention, despite their inability to participate directly. In fact, Wellington Delaney Moses, a convention delegate, described the women as having “come to the rescue,” demonstrating the significance of women’s fundraising.[5]

Aside from such causes that were specific to the conventions, Black women also used the conventions to promote their fundraising efforts. The 1865 Sacramento Convention drew attention to a Committee of Ladies of the Siloam Baptist Church who were holding a “Fruit Festival” to help finance the building of a new church.[6]

Churches played a central role not only in the convention movement but in Black women’s fundraising and organizing efforts in general. By holding events like the “Fruit Festival,” as well as picnics and fairs, Black women raised funds to build, buy, and sustain churches. Once such churches were established, they also served as channels through which Black women organized and participated in philanthropy and political activism involving fundraising.[7]

In 1872, William H. Hall, a key player in the California Conventions suggested that a group of twenty women take charge of the fundraising efforts at Bethel Church in San Francisco. This particular committee was raising funds to support equal school facilities and the admission of Black students into public schools. Hall asserted that a group of women “would soon raise the required amount without any trouble,” further demonstrating how Black women were valued within the movement for their dedication to fundraising.[8]

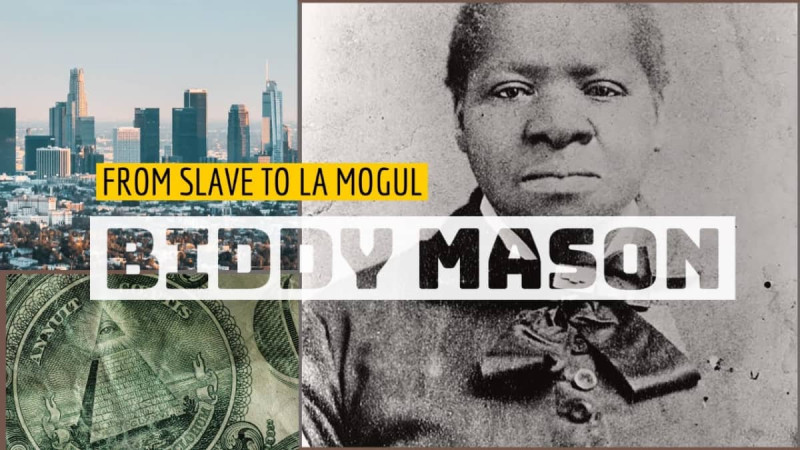

Black women’s fundraising was intimately tied with community organizing, and generally involved larger groups of women. However, there were individual women in California who contributed to the cause as well. Biddy Mason, a successful Black midwife, nurse, and former slave who lived in Los Angeles, was known for her philanthropic work and fundraising efforts.

One of her contributions to the Los Angeles community was that she funded the first African Methodist Episcopal church of the city, and she single-handedly supported the church during its early years when it was financially unstable.[9]

Mason was known for her charity to the poor and imprisoned people of Los Angeles, often donating large amounts of money to people in need.[10] A contemporary of Mason, Mary Ellen Pleasant was another woman in California who earned wealth in her own name and dedicated her time and money to the Black community.[11]

Pleasant moved to San Francisco from New England and was able to earn her wealth by performing domestic services and running a boarding house. She used her wealth and position of relative power to fight for Black equality, and was even able to bring a lawsuit against a railroad company for throwing her off of a segregated streetcar.[12]

The work of both Mason and Pleasant demonstrates the wide variety of social and political causes Black women fundraised for and organized around. Within the convention movement, women were often prevented from participating directly, and the work they contributed to the cause was often unseen. Black women’s fundraising, however, was a fairly visible form of women’s activism. Furthermore, it was one of the few ways that women were actually encouraged to participate.

For this reason, there are so many rich examples of Black women helping the convention movement and the overall movement for Black equality, by donating their money, time, and tireless efforts to the myriad causes they deemed important.

CREDITS

Written by Lila Gyory. Taught by Sharla Fett, History 213, Occidental College, Spring, 2016.

REFERENCES

[1] California State Convention of the Colored Citizens (1865 : Sacramento, CA), “Proceedings of the California State Convention of the Colored Citizens, Held in Sacramento on the 25th, 26th, 27th, and 28th of October, 1865,” ColoredConventions.org, accessed April 28, 2016, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/268.

[2] Lawrence B. de Graaf, ed.,Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California (United States: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, 2001), 112.

[3] Marne L. Campbell, “African American Women, Wealth Accumulation, and Social Welfare Activism in 19th-Century Los Angeles,” Journal of African American History 97, no. 4 (Fall 2012), 395.

[4] Second Annual Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California (1856 : Sacramento, CA), “Proceedings of the Second Annual Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California, Held in the City of Sacramento, Dec. 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th, 1856,” ColoredConventions.org, accessed April 28, 2016, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/266.

[5] Ibid.

[6] California State Convention of the Colored Citizens (1865 : Sacramento, CA), “Proceedings of the California State Convention of the Colored Citizens, Held in Sacramento on the 25th, 26th, 27th, and 28th of October, 1865.,” ColoredConventions.org, accessed April 28, 2016, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/268.

[7] de Graaf, Seeking El Dorado, 111.

[8] “Educational Public Meeting at Bethel Church,” Elevator, 27 April, 1872. California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, .

[9] de Graaf, Seeking El Dorado, 18.

[10] Kenneth G. Goode, California’s Black Pioneers: A Brief Historical Survey (Santa Barbara: McNally & Loftin, 1973), 91.

[11] Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, “The Making Of ‘Mammy Pleasant’: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco,” American Historical Review 111 no. 3 (2006): 837-838.

[12] Ibid.

Black women worked as seamstresses, hairdressers, maids, cooks, teachers, and boarding house owners, among other forms of labor.[1]

There were various legal and social structures in place that served to hinder women’s involvement in the work force; however, the reality was that many Black women did not have the financial option of not working and were thus able to find ways of earning income.[2]

This did not mean that Black women had access to political power, even within the conventions and the movement for Black equality. Women were often barred or discouraged from participating.[3] Thus, they found ways to contribute to the cause in their own way, on their own time: fundraising and community organizing.

Within the 1856 Sacramento Convention minutes, there are two references to women’s fundraising. A group of women from Placerville, in El Dorado County, raised $146, with the intention of supporting the State Executive Committee that was fighting to legalize Black testimony in court.[4]

A group of women from San Francisco also formed a Mirror Association to support the Black newspaper, Mirror of the Times, at a time when it was lacking funding. This fundraising effort is especially significant due of the importance of the Black press to the convention movement. The fact that Black women rallied around the Mirror to provide funding shows their dedication to the specific causes of the convention, despite their inability to participate directly. In fact, Wellington Delaney Moses, a convention delegate, described the women as having “come to the rescue,” demonstrating the significance of women’s fundraising.[5]

Aside from such causes that were specific to the conventions, Black women also used the conventions to promote their fundraising efforts. The 1865 Sacramento Convention drew attention to a Committee of Ladies of the Siloam Baptist Church who were holding a “Fruit Festival” to help finance the building of a new church.[6]

Churches played a central role not only in the convention movement but in Black women’s fundraising and organizing efforts in general. By holding events like the “Fruit Festival,” as well as picnics and fairs, Black women raised funds to build, buy, and sustain churches. Once such churches were established, they also served as channels through which Black women organized and participated in philanthropy and political activism involving fundraising.[7]

In 1872, William H. Hall, a key player in the California Conventions suggested that a group of twenty women take charge of the fundraising efforts at Bethel Church in San Francisco. This particular committee was raising funds to support equal school facilities and the admission of Black students into public schools. Hall asserted that a group of women “would soon raise the required amount without any trouble,” further demonstrating how Black women were valued within the movement for their dedication to fundraising.[8]

Black women’s fundraising was intimately tied with community organizing, and generally involved larger groups of women. However, there were individual women in California who contributed to the cause as well. Biddy Mason, a successful Black midwife, nurse, and former slave who lived in Los Angeles, was known for her philanthropic work and fundraising efforts.

One of her contributions to the Los Angeles community was that she funded the first African Methodist Episcopal church of the city, and she single-handedly supported the church during its early years when it was financially unstable.[9]

Mason was known for her charity to the poor and imprisoned people of Los Angeles, often donating large amounts of money to people in need.[10] A contemporary of Mason, Mary Ellen Pleasant was another woman in California who earned wealth in her own name and dedicated her time and money to the Black community.[11]

Pleasant moved to San Francisco from New England and was able to earn her wealth by performing domestic services and running a boarding house. She used her wealth and position of relative power to fight for Black equality, and was even able to bring a lawsuit against a railroad company for throwing her off of a segregated streetcar.[12]

The work of both Mason and Pleasant demonstrates the wide variety of social and political causes Black women fundraised for and organized around. Within the convention movement, women were often prevented from participating directly, and the work they contributed to the cause was often unseen. Black women’s fundraising, however, was a fairly visible form of women’s activism. Furthermore, it was one of the few ways that women were actually encouraged to participate.

For this reason, there are so many rich examples of Black women helping the convention movement and the overall movement for Black equality, by donating their money, time, and tireless efforts to the myriad causes they deemed important.

CREDITS

Written by Lila Gyory. Taught by Sharla Fett, History 213, Occidental College, Spring, 2016.

REFERENCES

[1] California State Convention of the Colored Citizens (1865 : Sacramento, CA), “Proceedings of the California State Convention of the Colored Citizens, Held in Sacramento on the 25th, 26th, 27th, and 28th of October, 1865,” ColoredConventions.org, accessed April 28, 2016, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/268.

[2] Lawrence B. de Graaf, ed.,Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California (United States: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, 2001), 112.

[3] Marne L. Campbell, “African American Women, Wealth Accumulation, and Social Welfare Activism in 19th-Century Los Angeles,” Journal of African American History 97, no. 4 (Fall 2012), 395.

[4] Second Annual Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California (1856 : Sacramento, CA), “Proceedings of the Second Annual Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California, Held in the City of Sacramento, Dec. 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th, 1856,” ColoredConventions.org, accessed April 28, 2016, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/266.

[5] Ibid.

[6] California State Convention of the Colored Citizens (1865 : Sacramento, CA), “Proceedings of the California State Convention of the Colored Citizens, Held in Sacramento on the 25th, 26th, 27th, and 28th of October, 1865.,” ColoredConventions.org, accessed April 28, 2016, https://omeka.coloredconventions.org/items/show/268.

[7] de Graaf, Seeking El Dorado, 111.

[8] “Educational Public Meeting at Bethel Church,” Elevator, 27 April, 1872. California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, .

[9] de Graaf, Seeking El Dorado, 18.

[10] Kenneth G. Goode, California’s Black Pioneers: A Brief Historical Survey (Santa Barbara: McNally & Loftin, 1973), 91.

[11] Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, “The Making Of ‘Mammy Pleasant’: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco,” American Historical Review 111 no. 3 (2006): 837-838.

[12] Ibid.

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network