From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

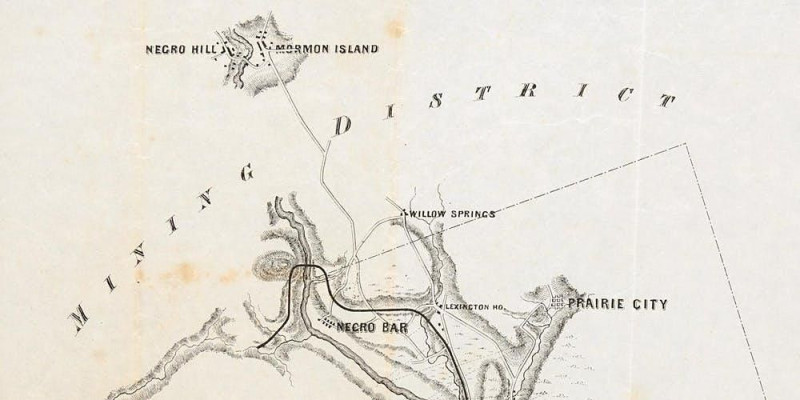

Golden Harvest Ceremony - Growing food in Historic Negro Bar, Lake Natoma, California

1848 Negro Hill, Mormon Island and Negro Bar Gold Mining District on Ancient Indigenous Lands in California. “It’s important to keep the focus squarely on the culprit that brought us to this point today. And that’s the US government. Its subtle and overt expansion of White supremacy is to blame here. These are two incredibly aggrieved, hyper-marginalized groups,”

Black Creeks finally get their day in court

Thursday could mark a turning point in Native American history. A hearing is scheduled about Black claims to Native membership. More specifically, the hearing will address the long-running demands of the descendants of Black people who were enslaved by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation that they be granted tribal citizenship and corresponding rights.

Following the Civil War, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation was required to accept as citizens the people of African descent it had once enslaved. But a 1979 change to the tribe’s constitution defined citizenship “by blood.” As a result, Black Creeks and their descendants, known as Freedmen, were effectively expelled.

Damario Solomon-Simmons, a civil rights attorney representing the two plaintiffs in the lawsuit, said that he feels confident that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation District Court will decide in his favor.

A descendant of Black Creeks, Solomon-Simmons has been involved in the citizenship battle for years. In 2018, he filed a federal lawsuit, but it was dismissed. (His grandmother was a plaintiff, but she died in 2019.)

Solomon-Simmons filed a petition in March 2020, and says that the tribe’s 1979 decision was “completely racist” and “erroneous.”

“It’s 100 percent anti-Black discrimination,” he told CNN. “They’re telling you that if you’re Black and/or (had) enslaved (ancestors), you can’t be a member of our nation.”

Solomon-Simmons said that the constitution not only strips Black Creeks of their citizenship—it also prevents them from securing the benefits given to tribal members: health care, education, housing, scholarships, cash assistance and more.

Officials from the Muscogee (Creek) Nation insist that the tribe’s citizenship requirements have nothing to do with race.

Spokesman Jason Salsman told CNN in an email that the nation’s citizenship is diverse, and includes Black Americans, Spanish people, Mexicans and Asians.

But he noted that the tribe has a “traumatic history” with people who aren’t Creek by blood, and that this is a “challenging issue” for many citizens.

“I can't speak for the leaders of 43 years ago when this decision took place,” Salsman said. “But it should hardly be surprising that a nation like ours that has endured attempts at extermination, removal and other unjust federal policies enforced by outsiders would seek a constitution that requires Creek Indian ancestry and blood lineage among its citizens and leaders.”

He added, “The matter before the Court is not a question of race but rather to determine whether our government is obligated by treaty to enroll individuals as citizens who are not Creek Indians.”

David Hill, the principal chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, underscored in an April 2021 letter the knottiness of this history, and the significance of confronting it.

“The question of the enrollment status of the descendants of Creek Freedmen is an extremely complex one,” he wrote, “born in an era when African Americans and Native Americans alike faced traumatic injustices at the hands of the US government. … As good leaders, it is important for us to listen, acknowledge and openly engage with our communities and our citizens. When these issues arise, they are opportunities that allow us to reconsider if our policies are still reflective of who we are as a Nation.”

Black Creeks have reason to be hopeful about their cause, which isn’t unique. Just last year, the Cherokee Nation jettisoned from its constitution language that defined citizenship purely by blood.

“The Cherokee Nation’s actions have brought this longstanding issue to a close and have importantly fulfilled their obligations to the Cherokee Freedmen,” Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet secretary, said in a May 2021 statement. “We encourage other Tribes to take similar steps to meet their moral and legal obligations to the Freedmen.”

Here’s a closer look at citizenship struggles dividing the Muscogee (Creek) Nation:

A short history of Black and Native American interactions

To understand some of the challenges beleaguering Black Creeks’ in our present day, let’s rewind to the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

During this period, the US government actively sought to “civilize” independent, self-governing tribal nations—Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and Cherokee—by forcing on them the privatization of land and the use of enslaved people for labor.

Many of these nations, especially the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, didn’t practice slavery in the way people tend to picture the institution.

“It wasn’t chattel slavery, where people would lose their humanity and become property,” Caleb Gayle, a professor of practice at Northeastern University and the author of the 2022 book, “We Refuse to Forget: A True Story of Black Creeks, American Identity and Power,” told CNN.

“It was, instead, a practice called kinship slavery. People were still peers. Slave identity wasn’t passed down from generation to generation. People broke bread and were seen as equals.”

He added that a certain level of nuance is necessary when discussing slavery within the context of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

“There’s been interaction between Black people and Indigenous nations for a very long time,” Gayle said. “That connection was further fortified, and usually forcibly, through the project of civilization that the US government enforced again and again.”

In 1866, in the aftermath of the Civil War, peace treaties granted not only emancipation but also tribal citizenship to Black people who had been enslaved by Native American nations, which had been forced to participate in the conflict to an extent.

With the passage of the Dawes Act in 1887, the US government sought to identify who would be on which citizenship roll. Some ended up on the “by blood” roll; others, on the Freedmen roll.

In 1979, when the Muscogee (Creek) Nation altered its constitution, those on the Freedmen roll were no longer able to keep the citizenship status they’d had for decades.

“Even if your ancestors had never been slaves, even if they’d been adopted into the nation, even if they never had the stain of slavery on them, if you were on the Freedmen roll—often because your ancestors looked a certain way—the constitutional change immediately kind of nullified your claim to the citizenship you once had,” Gayle said. “And that’s what changed things.”

Rhonda Grayson is intimately familiar with this history and its effects. She’s one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, and said that her ancestors were enslaved by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

She’s among the hundreds of Black Creek descendants who’ve unsuccessfully applied for citizenship since 1979. She applied in 2019, she recalled, but was denied; her appeal also was denied.

Grayson explained that she wants the Muscogee (Creek) Nation to issue an apology to Black Creeks for discarding them.

“My motivation is redemption for my ancestors. They suffered just like any other Native American. They worked and built the Creek Nation to what it is today,” she said. “We’re fighting for our tribal rights. We’re entitled to them.”

Grappling with experiences of exclusion

The disputes ricocheting throughout the Muscogee (Creek) Nation offer us an opportunity to reconfigure the way we think about identity.

In fact, we may already be starting to see this change.

In February 2021, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled that the nation had to remove “by blood” from its constitution.

The decision meant that the descendants of Black people once enslaved by the Cherokee Nation would have the right to tribal citizenship.

“Freedmen rights are inherent,” as Cherokee Nation Supreme Court Justice Shawna S. Baker wrote in the opinion. “They extend to descendents of Freedmen as a birthright springing from their ancestors’ oppression and displacement as people of color recorded and memorialized in Article 9 of the 1866 Treaty.”

For many, especially Black Creeks, this development offers hope that they might achieve a similar outcome.

Crucially, as citizenship conversations continue, we must maintain precision and sensitivity, Gayle urged.

“It’s important to keep the focus squarely on the culprit that brought us to this point today. And that’s the US government. Its subtle and overt expansion of White supremacy is to blame here. These are two incredibly aggrieved, hyper-marginalized groups,” he said.

In this light, Gayle added, “it’s impossible not to feel where the Muscogee (Creek) Nation is coming from when folks say, ‘We’re tired of being told who we are and being forced to modify and to accommodate.’ And it’s impossible not to feel where Black Creeks are coming from when they say, ‘Yes, we understand that—but we have a shared history that’s so potent and powerful as well.’”

Thursday could mark a turning point in Native American history. A hearing is scheduled about Black claims to Native membership. More specifically, the hearing will address the long-running demands of the descendants of Black people who were enslaved by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation that they be granted tribal citizenship and corresponding rights.

Following the Civil War, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation was required to accept as citizens the people of African descent it had once enslaved. But a 1979 change to the tribe’s constitution defined citizenship “by blood.” As a result, Black Creeks and their descendants, known as Freedmen, were effectively expelled.

Damario Solomon-Simmons, a civil rights attorney representing the two plaintiffs in the lawsuit, said that he feels confident that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation District Court will decide in his favor.

A descendant of Black Creeks, Solomon-Simmons has been involved in the citizenship battle for years. In 2018, he filed a federal lawsuit, but it was dismissed. (His grandmother was a plaintiff, but she died in 2019.)

Solomon-Simmons filed a petition in March 2020, and says that the tribe’s 1979 decision was “completely racist” and “erroneous.”

“It’s 100 percent anti-Black discrimination,” he told CNN. “They’re telling you that if you’re Black and/or (had) enslaved (ancestors), you can’t be a member of our nation.”

Solomon-Simmons said that the constitution not only strips Black Creeks of their citizenship—it also prevents them from securing the benefits given to tribal members: health care, education, housing, scholarships, cash assistance and more.

Officials from the Muscogee (Creek) Nation insist that the tribe’s citizenship requirements have nothing to do with race.

Spokesman Jason Salsman told CNN in an email that the nation’s citizenship is diverse, and includes Black Americans, Spanish people, Mexicans and Asians.

But he noted that the tribe has a “traumatic history” with people who aren’t Creek by blood, and that this is a “challenging issue” for many citizens.

“I can't speak for the leaders of 43 years ago when this decision took place,” Salsman said. “But it should hardly be surprising that a nation like ours that has endured attempts at extermination, removal and other unjust federal policies enforced by outsiders would seek a constitution that requires Creek Indian ancestry and blood lineage among its citizens and leaders.”

He added, “The matter before the Court is not a question of race but rather to determine whether our government is obligated by treaty to enroll individuals as citizens who are not Creek Indians.”

David Hill, the principal chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, underscored in an April 2021 letter the knottiness of this history, and the significance of confronting it.

“The question of the enrollment status of the descendants of Creek Freedmen is an extremely complex one,” he wrote, “born in an era when African Americans and Native Americans alike faced traumatic injustices at the hands of the US government. … As good leaders, it is important for us to listen, acknowledge and openly engage with our communities and our citizens. When these issues arise, they are opportunities that allow us to reconsider if our policies are still reflective of who we are as a Nation.”

Black Creeks have reason to be hopeful about their cause, which isn’t unique. Just last year, the Cherokee Nation jettisoned from its constitution language that defined citizenship purely by blood.

“The Cherokee Nation’s actions have brought this longstanding issue to a close and have importantly fulfilled their obligations to the Cherokee Freedmen,” Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet secretary, said in a May 2021 statement. “We encourage other Tribes to take similar steps to meet their moral and legal obligations to the Freedmen.”

Here’s a closer look at citizenship struggles dividing the Muscogee (Creek) Nation:

A short history of Black and Native American interactions

To understand some of the challenges beleaguering Black Creeks’ in our present day, let’s rewind to the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

During this period, the US government actively sought to “civilize” independent, self-governing tribal nations—Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and Cherokee—by forcing on them the privatization of land and the use of enslaved people for labor.

Many of these nations, especially the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, didn’t practice slavery in the way people tend to picture the institution.

“It wasn’t chattel slavery, where people would lose their humanity and become property,” Caleb Gayle, a professor of practice at Northeastern University and the author of the 2022 book, “We Refuse to Forget: A True Story of Black Creeks, American Identity and Power,” told CNN.

“It was, instead, a practice called kinship slavery. People were still peers. Slave identity wasn’t passed down from generation to generation. People broke bread and were seen as equals.”

He added that a certain level of nuance is necessary when discussing slavery within the context of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

“There’s been interaction between Black people and Indigenous nations for a very long time,” Gayle said. “That connection was further fortified, and usually forcibly, through the project of civilization that the US government enforced again and again.”

In 1866, in the aftermath of the Civil War, peace treaties granted not only emancipation but also tribal citizenship to Black people who had been enslaved by Native American nations, which had been forced to participate in the conflict to an extent.

With the passage of the Dawes Act in 1887, the US government sought to identify who would be on which citizenship roll. Some ended up on the “by blood” roll; others, on the Freedmen roll.

In 1979, when the Muscogee (Creek) Nation altered its constitution, those on the Freedmen roll were no longer able to keep the citizenship status they’d had for decades.

“Even if your ancestors had never been slaves, even if they’d been adopted into the nation, even if they never had the stain of slavery on them, if you were on the Freedmen roll—often because your ancestors looked a certain way—the constitutional change immediately kind of nullified your claim to the citizenship you once had,” Gayle said. “And that’s what changed things.”

Rhonda Grayson is intimately familiar with this history and its effects. She’s one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, and said that her ancestors were enslaved by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

She’s among the hundreds of Black Creek descendants who’ve unsuccessfully applied for citizenship since 1979. She applied in 2019, she recalled, but was denied; her appeal also was denied.

Grayson explained that she wants the Muscogee (Creek) Nation to issue an apology to Black Creeks for discarding them.

“My motivation is redemption for my ancestors. They suffered just like any other Native American. They worked and built the Creek Nation to what it is today,” she said. “We’re fighting for our tribal rights. We’re entitled to them.”

Grappling with experiences of exclusion

The disputes ricocheting throughout the Muscogee (Creek) Nation offer us an opportunity to reconfigure the way we think about identity.

In fact, we may already be starting to see this change.

In February 2021, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled that the nation had to remove “by blood” from its constitution.

The decision meant that the descendants of Black people once enslaved by the Cherokee Nation would have the right to tribal citizenship.

“Freedmen rights are inherent,” as Cherokee Nation Supreme Court Justice Shawna S. Baker wrote in the opinion. “They extend to descendents of Freedmen as a birthright springing from their ancestors’ oppression and displacement as people of color recorded and memorialized in Article 9 of the 1866 Treaty.”

For many, especially Black Creeks, this development offers hope that they might achieve a similar outcome.

Crucially, as citizenship conversations continue, we must maintain precision and sensitivity, Gayle urged.

“It’s important to keep the focus squarely on the culprit that brought us to this point today. And that’s the US government. Its subtle and overt expansion of White supremacy is to blame here. These are two incredibly aggrieved, hyper-marginalized groups,” he said.

In this light, Gayle added, “it’s impossible not to feel where the Muscogee (Creek) Nation is coming from when folks say, ‘We’re tired of being told who we are and being forced to modify and to accommodate.’ And it’s impossible not to feel where Black Creeks are coming from when they say, ‘Yes, we understand that—but we have a shared history that’s so potent and powerful as well.’”

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network