Paramilitary Panda: WWF Land Grabs Rooted in Covert Apartheid History

In 2019, BuzzFeed News broke several stories detailing human rights violations by the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF). The publication found that, since 2009, as part of its “anti-poaching” efforts, the WWF has armed, trained, and funded paramilitary units, located in six different countries, that committed various abuses — torture, sexual assaults, and murder of local villagers. The non-government organization (NGO) was also found to have evicted tens of thousands of indigenous residents to make room for Chitwan National Park in Nepal.

BuzzFeed portrayed these abuses as a dangerous — but fairly recent — side effect of the conservation movement’s increasingly militant war against well-armed poachers.

The truth — barely touched upon by mainstream media — is much more insidious than that. The WWF serves a larger purpose: for powerful interests to cordon off land for the exploitation of natural resources. It may even serve as a cover for covert military operations.

To unpack these loaded claims, the story of WWF’s militancy will be broken into two parts: the history of the organization’s founder and his involvement in clandestine activities, followed by its more recent alliance with corporate and military partners.

Part I - Green Spies, Gunships and Lies

WWF’s Origins in the Shadow World

The WWF was founded in 1961 by Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld, the German husband to Holland’s Princess Juliana. As the Prince sought a long-term funding source for the WWF, one of South Africa’s wealthiest businessmen, Anton Rupert, joined the organization as the president of its South African chapter. Rupert helped to establish what became The 1001: A Nature Trust, a secretive group (the word “cabal” instantly comes to mind) made up of the Prince and one thousand other members contributing $10,000 to the WWF.

Though the list of members is hidden even to the WWF board, names that were leaked to the public in the 1980s include powerful people both renowned and reviled. A long list of industrialists and politicians in the group included: Henry Ford; Anheuser-Busch’s August A. Busch; IBM’s Tom Watson; Stephen Bechtel of the Bechtel Corporation; Harry Oppenheimer of South African-British mining giant Anglo American Corporation; Muslim spiritual leader and billionaire Karim Aga Khan; Chase Manhattan Bank’s David Rockefeller; the U.K.’s Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh and future WWF president; British Petroleum General Director Sir Eric Drake; Shell CEO and future WWF president John H. Loudon; Phillip Morris CEO Joseph Cullman III; and former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

Sitting alongside them were U.S.-supported dictator of Zaire Mobutu Seko Seko; arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi; the older brother of Osama bin Laden, Sheikh Salim Bin Laden; Franco’s Minister of Information, Manuel Fraga-Iribarne; rainforest-destroying billionaire Daniel K. Ludwig; embezzler and drug and arms trafficker Robert Vesco; Swiss embezzler Tibor Rosenbaum; and Agha Hasan Abedi, the founder of Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), a bank used by drug traffickers and the CIA alike to launder funds. BCCI was involved in the CIA’s scheme to funnel money to the mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan, eventually leading to the rise of Osama bin Laden.

The Prince seemed to be fond of secretive clubs, as he also founded—get this—the Bilderberg Group! The organization sees industrialists, politicians and other members of the world’s power elite meet regularly to “foster dialogue between Europe and North America.” In the public mind, the Bilderberg meetings are associated with not-completely-unfounded conspiracy theories about the richest people on the planet making decisions that influence the workings of the world.

As if some of the most powerful people meeting in secret weren’t enough, to recruit U.S. involvement in the group, Bernhard turned to Eisenhower’s CIA director at the time, Walter Bedell Smith. Not incidentally, the first meeting of the Bilderberg Group was funded by the CIA.

As fate or political machinations would have it, the Prince was well-connected to the shadowy intelligence agency. A 1976 New York Times article described Bernhard as being close friends with infamous former CIA director Allen Dulles, associated with some of the U.S.'s favorite coup d’etats.

In one CIA report, Bernhard offered the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) a Dutch intelligence officer to act as an agent for the spy organization.

The relationship with U.S. and European intelligence seems to have gone back to the Dutch resistance to the Nazis.

Here it’s worth expanding on Bernhard’s ties to Nazi intelligence. Before he rose to royal heights, Bernhard was part of the mounted SS troops, the "Reiter-SS", and later a member of the paramilitary National Socialist Motor Corps. In 1934, he joined IG Farben, which later became known for supplying Zyklon B to the Nazi gas chambers, and worked as an operative for its Berlin N.W. 7 office, the chemical giant’s industrial espionage division.

A 1973 telegram demonstrates that Bernhard had duplicitous intentions for his charity from very early on. In the note, from U.S. diplomat Kingdon Gould, Jr. to U.S. Secretary of State and notorious war fiend Henry Kissinger, Gould writes that Bernhard discussed the possibility of establishing a nature park in the Sinai desert that could also be used as a demilitarized zone at the expense of the WWF.

Gould suggested that “OBVIOUS ADVANTAGES WOULD FLOW FROM HAVING A GENUINE AND ENORMOUSLY IMPORTANT NON-HUMAN REASON FOR MINIMIZING HUMAN ACTIVITY IN THE AREA, AND FROM THE INTRODUCTION OF AN ECOLOGICALLY-ORIENTED INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION SUCH AS THE WORLD WILDLIFE FUND. IT WOULD ALSO SERVE AS A FACE-SAVING DEVICE FOR ANY COUNTRY WHICH MUST YIELD SOVEREIGNTY TO A DEMILITARIZED AREA.”

In a follow-up telegram, Gould said he discussed the idea with an Israeli ambassador and that the Israelis were open to the idea.

From this background, we come to know that the founder of the WWF was a Western intelligence asset and nearly lifelong spy firmly entrenched in secret networks of powerful world players representing both the underworld and huge corporate and national interests. We also learn that Prince Bernhard offered the WWF up as a cover to national militaries. Next, we’ll see the WWF actually deployed as such a cover.

Operation Lock: Anti-Poaching as Cover Story

Within WWF, Bernhard would have the opportunity to launch his own CIA-style covert operations. In 1987, the NGO launched a project known as “Operation Lock,” ostensibly created to infiltrate and dismantle the African rhino horn and ivory trade. To execute the project, WWF hired KAS Enterprises, a private military firm that was also used to wage war on the enemies of apartheid South Africa.

In 1987, the Prince and WWF-South Africa functionary John Hanks paid a firm called KAS Enterprises to train anti-poaching units and penetrate illegal trading networks to arrest poachers throughout Africa. To fund Operation Lock, Bernhard sold two valuable paintings from the royal Dutch art collection and used the WWF to direct the funds to KAS Enterprises.

KAS was created by Sir David Stirling, who established the Special Air Service (SAS), a commando unit of the British Army—sort of like the Green Berets, but with British accents. After World War Two, Stirling worked as a private mercenary and spy, setting up fake businesses, including a film distribution firm, that ran cover for the activities of British intelligence agency MI6 around the globe.

He was no James Bond, preventing the end of the world with wit and cunning. Working with MI6, the right-wing Stirling helped facilitate arms deals to Saudi Arabia and other parties in the Middle East, attempted to overthrow the Yemeni and Libyan governments in the early 1960s and 70s, and provided paramilitary security for African and Middle Eastern leaders (it is believed that he obtained arms for the Yemen raid through 1001 Club member Adnan Khashoggi). In 1974, he also established elaborate counterinsurgency plans for use within the U.K. in the event that the British government might break down due to civil unrest. After that, he worked to infiltrate and undermine trade unions in the U.K., as well.

The KAS team was as militant and secretive as its SAS membership would suggest, according to the South African police with whom they worked. The squad even considered getting around sanctions placed on the apartheid regime—a practice that could have involved illegal maneuvering—to obtain high-tech gadgets for its mission.

In one leaked report from KAS, the group says that the “US Department of the Interior (US Fish and Wildlife Service) are keen” to provide the mercenaries with technical assistance for tracking rhino horns using transmitters, “[h]owever sanctions prevent the passage of technical assistance to the [Republic of South Africa].” The report then suggests that it is possible to circumvent sanctions against the apartheid regime “by sending the technical equipment to KAS in London.”

Stephen Ellis, who broke a story on Operation Lock for the Independent in 1991, describes in his research how South African Military Intelligence exploited the trade of wildlife products throughout Africa for the larger effort of destabilizing the enemies of apartheid.

“All of these trades tended to implicate senior government officials throughout [Africa], either because of their value, or their illegal or semi-legal nature required traders to buy political protection at a high level,” Ellis writes. “Hence, the infiltration of these networks by South African Military Intelligence was not only a means of making money but also a useful tool for South Africa’s secret servants to penetrate state machineries in pursuit of their strategy of destabilization.”

In 1995, the post-apartheid South African government under Nelson Mandela investigated Operation Lock. In addition to uncovering evidence that KAS was involved in trafficking illegal wildlife products themselves, the inquiry learned that the project’s leader, former SAS Commander Ian Cooke, offered to deliberately undermine the struggle against apartheid. Documents obtained during the inquiry discuss Cooke’s aims to use the ivory trade network to gain intelligence on “anti-South African countries” and “monitor anti-South African bodies.” Evidence has also been uncovered that KAS had a list of people it intended to assassinate.

In an interview with South African secret service members, documentary filmmaker Kevin Dowling learned that KAS actually fought Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC), the leading anti-apartheid group in the nation, using the UNESCO heritage site of Kruger National Park to do so.

“The KAS mercenaries used the Kruger National Park as a training grounds to train paramilitary units such as the Koevoet Squad from Namibia,” Dowling relayed in an interview for the book PandaLeaks. “They were then deployed against the ANC as part of the so-called ‘third force’. This officially non-existent execution squad murdered around 6,000 opponents of the apartheid regime in South Africa.”

KAS also partnered with the Rhino and Elephant Foundation, whose president, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, led a movement that was paid in secret by South African police to oppose the ANC. Buthelezi’s Inkatha movement additionally created hit squads trained by South African Military Intelligence at secret bases in Namibia and South Africa.

South Africa wasn’t alone in its support of the Inkatha Freedom Party. The group received $2.6 million from the U.S. Congress in 1991 through the U.S. Agency for International Development and the National Endowment for Democracy (U.S. agencies known for their efforts to destabilize foreign governments), despite the recent revelations that the Inkatha group had been working with the apartheid regime.

KAS had its own ties to apartheid. According to Julian Rademeyer, author of Killing for Profit, “One senior KAS employee had assisted the Angolan rebel movement UNITA with a propaganda campaign and had close ties with the South African military attaché in London.” UNITA was the South African government and the CIA’s favored armed force during the civil war in Angola.

The Mandela government’s inquiry suggested that, though Operation Lock was not an official WWF project, the WWF “cannot contend that it had no knowledge of Lock or was totally divorced from it” because it was discussed in internal organization documents. Though the organization as a whole may not have been aware of the specific exploits of the KAS team, we have evidence that WWF’s founder and at least one employee hired a team of British soldiers, led by an MI6 agent, that used a national park to train “anti-poaching” squads to kill enemies of apartheid. The fact that Bernhard funneled the money through WWF is key, as it provides cover for KAS activities as environmentally related.

WWF Fronts for Apartheid

That the non-profit was involved in fighting enemies of the South African apartheid state is not entirely surprising, if you know the background of billionaire WWF-South Africa president Anton Rupert. Rupert was closely connected to the Afrikaner Broederbond, the secret fascist group responsible for the implementation and maintenance of apartheid. Every prime minister and state president of the country was a member of the club from 1948 to 1994, when apartheid was ended.

Rupert also created or participated in numerous methods for obscuring financial transactions, including shell companies and legal loopholes, in order to do international business under the UN’s apartheid embargoes. This, combined with the way he internationalized the boards of his businesses to include influential people from Europe and North America, make Rupert’s establishment of The 1001: A Nature Trust particularly interesting.

The 1001: A Nature Trust was said to have an outsized influence from South Africans during apartheid, representing 60 of the 1001 members at the time. This included members of the Afrikaner Broederbond, such as the chairman of Volkskas, at one point the country’s largest Afrikaner bank; the chairman of the Federale mining and industrial group; and the former managing director of the Sanlam financial group, closely affiliated with the apartheid National Party. Other prominent members included the director of Mercabank, members of the country’s Defence Advisory Council, and several people implicated in the Muldergate scandal that involved the South African government using secret service funds to purchase control of local newspapers in other countries.

Because businesses in South Africa, including those of the WWF’s Anton Rupert, were accustomed to finding clever ways for circumventing international embargoes, it’s possible to imagine that Bernhard, Rupert, and other South African co-conspirators benefiting from the apartheid regime would understand how the WWF could be ued to launder money for Operation Lock, which is what Bernhard did when selling his paintings for the project. Moreover, the makeup of the 1001 club suggests that there were parties involved with WWF that could use the conservation organization to their advantage.

WWF Rangers Kill 57 People with Gunship

At the same time as KAS spread across the continent, the WWF gave Zimbabwe's Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management the money to purchase a helicopter purportedly to help protect the local black rhino population against poaching. Between February 1987 and April 1988, the helicopter was used to shoot and kill at least 57 poachers, according to journalist Paul Brown, who broke the story for The Guardian.

Former New York Times and New Yorker journalist Raymond Bonner, in his book on conservation, said of the WWF’s complicity: “The truth is the organisation knew that the helicopter would be used in operations in which poachers would be killed. Indeed, there had been a long and fierce debate within WWF about the project, and many on the staff were opposed because Zimbabwe's policy was ‘Shoot first, ask questions later,’ as one of those involved in the debate puts it. Providing the helicopter ‘made the policy more effective,’ he said. As for WWF's statement that it did not provide funds for arms or ammunition, the organisation's internal documents show that it was doing precisely that for at least one project in Tanzania in 1987.”

According to Independent reporter Stephen Ellis, Zimbabwe’s helicopter purchase was directly tied to KAS Enterprises: “KAS succeeded in working with Zimbabwean game wardens and funding a helicopter for anti-poaching operations in the Zambezi Valley.”

It’s important to note that Operation Lock saw the KAS team infiltrating governments and illegal trading networks throughout the continent. Commander Cooke’s squad also operated in Mozambique, the Central African Republic, Togo, Zambia, Swaziland, Namibia, Kenya and Zimbabwe. In Zimbabwe, Cooke made connections with members of the government’s Central Intelligence Organisation, as well as Glenn Tatham, the chief warden of Zimbabwe’s national parks responsible for the country’s “shoot-to-kill” policy toward poachers. In other words, there may have been other motives related to Operation Lock that we are unaware of that could account for the use of this gunship.

From South Africa to the U.S.

Prince Bernhard and KAS were clearly not conducting Operation Lock without the support of Western powers. Across the pond, WWF-US was involved in its own covert project, via former WWF-US President Curtis “Buff” Bohlen.

Before he joined the WWF-US as a director of government affairs in 1981, Bohlen worked for the State Department. Bohlen told journalist Elaine Dewar, for her book Cloak of Green, that, while with State, “he helped occasionally, did occasional assignments for” the CIA.

According to journalist Raymond Bonner, by 1989, WWF, neither International nor the U.S. branch, had come to a decision about whether or not to support a ban against ivory trading. The NGO wanted to respect the input of African client nations, some of whom were against banning the trade of ivory. However, to maintain a positive image with Westerners—who were generally against the murder of all animals—there was good reason to support a ban.

For reasons unclear to the WWF, Bohlen rallied the support of African countries whose economies depended on the ivory trade, all while making regular reports to the State Department. Bohlen then pushed WWF-US to announce a strong endorsement in favor of an international ban on June 1, 1989, forcing WWF-International to fall in line to avoid embarrassment.

Several days later, on June 5, 1989, then-President George H.W. Bush made his own announcement enacting a ban on ivory imports into the U.S., with WWF-US providing its seal of approval by gifting the president a stuffed elephant. This was proceeded by Margaret Thatcher’s news that the U.K. was following suit by instituting its own ivory ban.

Bohlen left his post at WWF just over six months later, in February 1990, to work for the State Department again as Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs under Bush Sr.

“It was Buff’s CIA days coming back to haunt us,” one senior WWF-US official told Bonner. “He really manipulated the system.”

Bonner also quotes a WWF staff member as saying they couldn’t wrap their head around Bohlen’s operation, asking, “Did he want to destabilize Africa?”

Such a question was not an entirely unreasonable one, given the activities associated with Operation Lock across the continent.

Economic Warfare

Buff Bohlen’s future boss, George Bush, had orchestrated his fair share of destabilization efforts. This included the Iran-Contra scandal, wherein the U.S. sold arms to Iran to fund the Contras to overthrow the socialist Sandinista government of Nicaragua; and Operation Cyclone, in which Islamist extremists were armed and trained to overthrow the socialist government in Afghanistan.

(Perhaps key side notes: both of the aforementioned operations involved members of the 1001 Club. Adnan Khashoggi was the arms dealer involved in Iran-Contra and Agha Hasan Abedi’s BCCI bank was used by the CIA to funnel money to the mujahideen in Operation Cyclone. Also adding to the connections is the fact that WWF-South Africa president and billionaire Anton Rupert sat on the board of Harken Energy, associated with influence peddling of the Bush family.)

More relatedly, under the Reagan administration (while Bush was Vice President), the U.S. supported apartheid intelligence activities via the CIA. In a March 1983 intelligence memo from the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) to the U.S. Department of Defense, obtained by author Hennie van Vuuren, there is a reference to the CIA training South African troops. Van Vuuren discovered numerous pieces of intelligence exchanged between the CIA and the South African Defense Force, including “the type of surface-to-air missiles held by the Angolan government.”

In 1988 to 1989, a covert intelligence unit within the South African military budgeted four intelligence visits from the U.S. and three visits to the U.S., meaning that the sharing of intelligence between the countries went both ways.

Van Vuuren goes on to describe the possible involvement of the South African government in the Iran-Contra scandal, including the possibility that the government transported arms to the Contras through a South African airline. The author also confirms that the CIA tipped off South African officials to the whereabouts of Nelson Mandela in 1962, leading to his arrest.

Bush Sr. was also known for ramping up the drug war, approving the 1033 program (formerly the 1208 program), which provided local and state police with military-grade equipment to enforce drug laws. As drug enforcement increased, so did the value of drugs, leading to more violence over the profits and more profits to the suppliers of law enforcement equipment. In some ways, the illegal wildlife trade mirrors that of the drug trade, in that prohibition has increased the value of goods on the black market and these markets provide off-the-books conduits for funds to covert operations. For instance, cocaine was used to further fuel the efforts of the Contras in Nicaragua. In Africa, thef South African Military Intelligence Directorate paid Rhodesian special forces, the Selous Scouts, in ivory.

Drawing on this background, along with the aforementioned CIA support for the apartheid government, it’s possible to infer the use by Western powers of a global ivory ban to destabilize the economies of African nations.

Raymond Bonner recounts that, at the time of the ivory ban debate, a group of researchers was charged with determining the impact of the ivory trade on elephant populations. One member, David Pearce, sent the team’s coordinator a memorandum representing the views of the group’s economists. Pearce explained that “by depriving countries of ivory sales, the ban was the equivalent of a $50 million tax on African governments; in addition, domestic carving industries in African countries would be severely hurt. Therefore, Pearce said, if there was going to be a ban, affected African countries should be compensated by the West with $100 million a year.” This information was never included in the group’s final report.

Tying these pieces together, it could be possible that the ban was put into place to destabilize African economies, increase the jurisdiction of U.S. military forces, and ensure the steady flow of arms and funding to paramilitary programs abroad, with the added benefit of using the ivory trade as a cover for whatever covert operations might be necessary. However, at this point, it has been difficult for this author to determine if the ivory ban really did have such an economic impact on African countries.

A Sinister Beginning

While the organization’s leadership may have been aware of the anti-poaching campaign, it may not have known about ulterior motives for that campaign. Bernhard, an asset for the CIA, along with MI6’s David Stirling, may have launched Operation Lock on behalf of partners within the South African regime, including Anton Rupert and other members of the WWF’s 1001 Club.

Any strange activities conducted by KAS, then, could be attributed to its cover story. When discovered by the public, training and arming death squads, killing anti-apartheid activists, spying on neighboring countries, and getting cash through off-the-books methods, could be and actually have been described as unconventional and heavy-handed methods to take on poachers.

Given links between the apartheid regime, the WWF, and western intelligence, Lock may have been just one among many covert attempts to maintain the apartheid government. One other project associated with the nature conservation organization could have involved the destabilization of African economies through the international ban of ivory trading.

If such a hypothesis were confirmed, Operation Lock would be just one instance of the use of the WWF as a front for nefarious actions by international power brokers. However, details about the WWF’s more recent history suggests that the green cover provided by WWF continues today.

Part II

The War on Poaching

While Operation Lock may have been controversial enough to hide from the public at the time, countless publications have written completely uncritical articles about what has become standard practice in conservation: heavily arming and training anti-poaching units in third world countries.

Groups ranging from WildlifeDirect, the Wildlife Conservation Fund and the African Wildlife Foundation to the WWF and Save the Elephants have been turning park rangers into paramilitary forces in an effort to combat poachers who are well-equipped. York University associate professor Elizabeth Lunstrum points out that national parks worldwide are becoming increasingly militarized, with former military forces found on both sides of the poaching war.

In government press communications and the mainstream media, one of the biggest motivators for the militarization of wildlife conservation is to take on terrorist groups, like Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram, who are said to receive substantial funding from the trade of illegal wildlife products.

For instance, in 2016, U.S. ambassador to the UN Samantha Power told officials and journalists that it was necessary to train and arm park rangers to take on Boko Haram, saying that “the criminal networks that profit from trafficking fuel corruption and generate funds that can be used to fuel other dangerous activities that pose a serious security threat, including terrorism.” At a 2013 meeting of the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI), Hillary Clinton said that al Shabab was also funding their operations with ivory trafficking.

News outlets too refer to a strong link between poaching and terrorism, including a post from CNN titled “How poaching fuels terrorism funding,” a story from the Washington Post dubbed “Break the link between terrorism funding and poaching,” and an Independent article headlined “British troops tackling elephant poachers selling ivory to fund terror.” “Zero Dark Thirty” director Kathryn Bigelow even created a short film called “Last Days” about ivory-funded terrorism.

However, numerous academic and institutional studies have determined that the link between terrorism and poaching is tenuous. A 2018 National Science Foundation-funded paper found that, in Cameroon, Boko Haram was more interested in stealing the cattle of pastoralists than elephant tusks to fund its operations. A report from a British think tank, the Royal United Services Institute, determined that poaching was linked to organized crime, rather than terrorism.

Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution, concluded: “[A]nalyses of the wildlife-trafficking-militancy-nexus are often shrouded in unproven assumptions and myths. Crucially, they divert attention from several uncomfortable truths with profound policy implications: First is that the nexus of militancy in wildlife trafficking constitutes only a sliver of the global wildlife trade and countering it will not resolve the global poaching crisis. Second, counterterrorism and counterinsurgency forces, even recipients of international assistance, also poach and smuggle wildlife and use anti-poaching and counterterrorism efforts as covers for displacement of local populations and land grabbing. Third, corruption among government officials, agencies, and rangers has far more profound effects on the extent of poaching and wildlife trafficking. And finally, local communities are often willing participants in the global illegal wildlife trade.”

Despite the lack of evidence regarding the ties between poaching and terrorism, both military and non-government organizations have been using the conceit as a means of blending the two for the sake of conservation. A WWF report summarizing a “wildlife crime workshop” in 2012 gives the impression that invoking military action in the anti-poaching field is a desired outcome by participants and that establishing links between wildlife crime and terrorism or other illegal activities are necessary to achieve it.

Crawford Allan, Senior Director of Wildlife Crime for TRAFFIC, a joint wildlife trade program between WWF and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, is noted to have said: “As nomenclature is an issue, one effective strategy may be ‘bundling’ this issue. We may be more successful in marketing the issue if we bundle the concepts of ‘wildlife’ and ‘crime’ with ‘military security’, ‘food security’, ‘wildlife decimation’, ‘trans-boundary security’ and other related issues such as illegal logging/timber trafficking and IUU fishing.”

Other suggestions made to further entwine wildlife policing and larger military efforts include “link[ing] revenues from the illegal wildlife trade to terrorist groups and/or international drug cartels, thereby triggering government military responses, such as the U.S. Department of Defense involvement under existing authorities.”

One comment states that “NGOs need to be able to collate [information] and pass it on in such a way that it can be disseminated to the intelligence community to achieve a higher profile.” Another describes the “necessary steps for engaging DOD”, saying, “The NGO community, ranger forces, and others must make a more convincing case if they want strong Military involvement. Many ranger forces in central Africa are para-military and DOD should be able to work with them on a military-to-military basis (understanding that precedents exist). For this to occur, this issue must meet the threshold for prioritization. Unless the USG raises the priority of this issue by making a clear connection founded in intelligence that wildlife crime is linked to drug trafficking and/or other illegal chains, this will not happen.”

For the WWF, the militarization of conservation has meant working closely with a variety of armed forces worldwide, including: the Indian Army, Nepal Army, the Thai military, the French military, the Cameroon Army, and more. The most powerful, of course, is the U.S. military. This is a result of the fact that the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has provided over $120 million to the WWF over time.

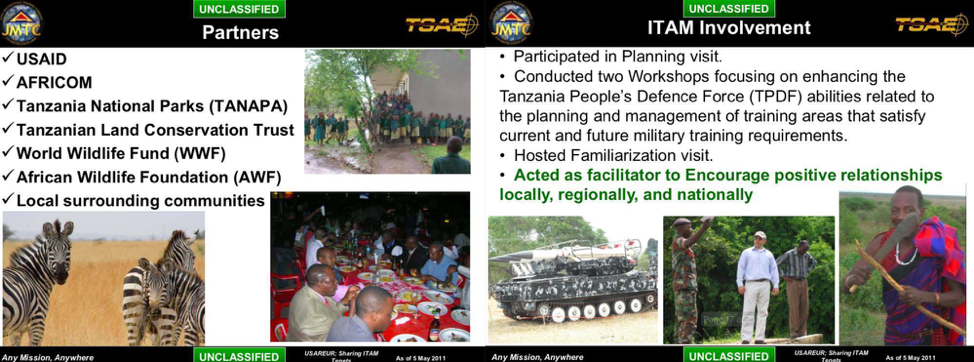

A May 5, 2011 presentation on projects in Tanzania, for instance, describes how AFRICOM, USAID, WWF and the African Wildlife Foundation were involved in the training of the Tanzania People’s Defense Forces to fight poaching in the Masai Steppe.

In a 2012 congressional hearing that included the WWF and its frequent partner Save the Elephants, wildlife conservancies praised the work of AFRICOM in the fight against poaching. Save the Elephants founder Iain Douglas-Hamilton said, “If we could have much more help with training maybe from the U.S. forces and, indeed, intelligence and surveillance and any of the resources that they could marshal, it would be a great help.”

Elizabeth Lunstrum explains that the military technology deployed in parks is becoming more advanced as well. Google provided WWF with a $5 million grant for the purchase of surveillance drones to be used at parks globally. This is just one drone program among many pieces of military tech now being used, according to Lunstrum.

“One (rather secretive) partnership is with the Denel Group, a state-owned aerospace and defense conglomerate that has loaned an unmanned aerial vehicle, Seeker 2, a drone, to SANParks to assist its anti-poaching efforts. ‘Details of the intervention,’ we are told, ‘cannot be released for security considerations and other key operational sensitivities.’ At a minimum, this ‘intervention’ brings military drone technology into Kruger—technology that can potentially lessen the problems of distance and invisibility posed by the park's expanse and dense topography,” Lunstrum writes. “In a far more well-publicized partnership, SANParks has received additional military aerial surveillance technology from the Ichikowitz Family Foundation, which is the charitable arm of the Paramount Group, itself the continent's largest privately owned defense and aerospace company. Their donation consists of a Seeker Seabird specialist reconnaissance aircraft equipped with a ‘FLIR Ball infrared detector [that] will deliver more enhanced and powerful observation capability to [Kruger's] rangers, making it very difficult for poachers to hide.,”

Other advanced technologies include: artificial intelligence, RFID, thermal imaging, gunshot detectors, snare detectors, and vehicle trackers. Douglas-Hamilton highlights the direction national parks are headed in during the congressional hearing, as he makes multiple requests for cooperation with DARPA for the application of advanced military technology on elephant collars:

“I think that DARPA have the intellectual resources, quite extraordinary ones. I know some of the people there, and we have discussed ideas for making the dream elephant collar or for putting up gunshot detectors in all the hills and integrating this into a system that is a sort of command and control system but at a local level where it is very easy to get the information fed back to a quick reaction force. In a way, antipoaching is like a minor guerilla war.”

In a 2017 congressional hearing, Carter Roberts, President and CEO of WWF, similarly requests “continued commitment and additional investment from the public and private sectors, there are a range of priority conservation challenges we might tackle via technology and innovation, including: Leverage U.S. technology experts and experts at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency to help solve the problem of ‘the needle in the haystack’ when it comes to technology solutions used in the field and illegal wildlife being trafficked in shipping containers.”

2017 actually saw the realization of the Save the Elephants gunshot tracking technology. Though not a collar, the device DARPA developed can determine the coordinates of gunshots based on ballistics soundwaves, even if a gunshot is fired from a weapon with a silencer on it.

There isn’t much empirical evidence that terrorist ground receive significant funding via illegal trading of wildlife products, yet the media and politicians continue to suggest the opposite. Given the fact that conservation NGOs like WWF desire support from the U.S. military, we might assume that this messaging is exactly what the NGOs are hoping to communicate.

Conservation as Guerilla Warfare

Douglas-Hamilton’s comparison to a guerilla war is an apt one, in that the distinction between poaching and warfare is often lost on the forces embedded within national park zones.

In one widely-publicized incident, a group of poachers from Chad and Sudan entered WWF-supported Bouba N'Djida National Park in Cameroon and killed 200 elephants, which resulted in the involvement of both the Cameroonian military and U.S. military and an in-person meeting between the President of Cameroon and U.S. General Carter F. Ham, Commander of U.S. AFRICOM.

Due to that incident, the Cameroon government's Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR) was brought in to collaborate with park guards. According to the aforementioned National Science Foundation report, the use of such military force could lead to abuse and repression of local indigenous groups without oversight.

“In light of the poacher-as-terrorist narrative, conservation interests can be trumped by national security concerns.” The report continues, “As the Warden of the park remembered, rather than engaging with conservation-trained staff there, the BIR had ‘taken over the park,’ often excluding the warden and trained eco-guards from their operations. These park officials' concerns converge with those of scholars like Duffy and Humphreys and Smith—that wars waged in the name of biodiversity can be used by state governments to justify repressive and coercive policies within their borders.”

That, however, may be exactly the point of intertwining military and park ranger forces, allowing the former to blend into the latter in order to perform covert operations.

Covert Conservation

Given the WWF’s history with Operation Lock, we might suspect continued military exploitation of the NGO as a cover for clandestine activities. Paramilitary forces that are free to roam in conservation parks, which have been the sites of battles with anti-state forces and often stretch across national borders, would be useful after all. And the U.S. government has a long history of funding paramilitary forces to exert control in foreign countries, most notably through Operation Condor in Latin America.

Exploring that train of thought, it’s worth understanding the work that USAID has sometimes been involved in. On its surface, USAID is an arm of the State Department used to provide money and resources to NGOs for development in third world countries. However, the division has been continuously linked to destabilization efforts by the U.S. government in nations around the world.

One of the most recent and famous examples was a USAID-backed social media network in Cuba called ZunZuneo, meant to encourage young Cubans to revolt against the government. Other examples include attempts to undermine and divide the Hugo Chavez government in Venezuela, stir up anti-Yanukovych protests in Ukraine, and facilitate the ouster of Fernando Lugo in Paraguay.

There is some evidence that USAID-funded programs and high-tech conservation tools could serve ulterior purposes. Keith Harmon Snow, an award winning journalist, and Georgianne Nienaber published an investigative series (previously available on the now-defunct COA News site) on the link between the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund-International (DFGFI) and business and government interests in Africa, based on extensive documentation and on-the-ground experience in the Great Lakes region of Africa.

The pair reported that, after the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund-International (DFGFI) could not account for over about $4.7 million in USAID funds with a standard A-133 form, the NGO was audited by a Department of Defense contractor, the Defense Contracts Audit Agency. The agency did not publish the outcome of its audit due to the “proprietary nature” of the audit.

The journalists claim that an anonymous source told them, “USAID is covering up for the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International.” The authors go on to say that remote sensing data created by DFGFI partner and geographic information systems company Esri was, “According to two independent inside sources… delivered directly by the DFGFI’s CEO Clare Richardson into the hands of Rwandan President Paul Kagame and the Rwandan Minister of Defense.”

The authors cite a “remote sensing expert”, who visited Esri operations, as saying, “These guys aren't looking for habitat. They are looking for oil, which is what they do, and they probably got funding for habitat assessment from USAID and are using the data to provide their owners with oil, minerals and uranium info. I'm not aware of any natural resource vegetative project that they have done in the past. It strictly sounds like taking the taxpayer dollar to fatten some oil guys pockets.”

An Esri press release quoted by the journalists explains that the remote sensing data can be used for other applications, including mineral explorations: “Beyond gorilla habitat analysis, GIS and remote sensing technology can also help the government update its maps, manage its agricultural lands, relocate refugees, and analyze the impact of their (refugee) camps (areas known to suffer from deforestation due to trees being used for firewood and temporary shelters), as well as explore for minerals.”

Harmon Snow and Nienaber also cite an anonymous source as saying, “The theory is that Rwanda lets the U.S. fly over their airspace to get oil and uranium information, and in return Rwanda gets defense maps.”

The investigation focuses on DFGFI, but WWF is a partner of DFGFI, is involved in some of the same conservation projects, and is a part of the same nexus of conservation groups that operate with USAID funding. In fact, WWF is also a partner of Esri, working with the company to create maps of data collected by WWF throughout the various territories in which it works.

Direct evidence of conservation agencies as covert operations, however, would be nearly impossible to come by outside of insider info or an Edward Snowden-type leak. Moreover, to understand the WWF as a tool of Western state and corporate power doesn’t necessarily require a narrative of spy agencies and covert ops.

Scramble for Africa

While WWF’s stated purpose is the conservation of wildlife in the countries where it operates, U.S. power may wish to utilize that conservation for specific purposes. Vice-Admiral Robert Moeller, military deputy to former commander of AFRICOM General William ‘Kip’ Ward, told a 2008 AFRICOM conference that the unit’s goal was “protecting the free flow of natural resources from Africa to the global market.” Moeller later wrote in 2010, “Let there be no mistake. AFRICOM’s job is to protect American lives and promote American interests.”

In fact, the blend of military and conservation in regions with vast natural resources serves a crucial purpose: the securitization of those resources for multinational corporations. WWF and other conservation non-profits are able to cordon off large swaths of land for multiple potential uses. The process begins by evicting indigenous communities from ancestral lands, preventing them from hunting for bushmeat or animal horns for cultural or survival purposes. To enforce authority over the land, these “poachers” may face waterboarding, sexual assault, whippings, beatings, and murder. Some areas are then conserved to raise money for the NGO and private interests through ecotourism and trophy hunting; others can be reserved for extraction by WWF partners.

Non-governmental organization Survival International (SI) has documented this process with regards to protected areas in Congo, Cameroon and the Central African Republic. According to members of indigenous Baka and Bayaka tribes in the Congo Basin region that spans these countries, the tribespeople have been labelled as “poachers” and forced off of their ancestral lands by WWF-funded and trained park rangers to make way for various nature parks.

While these tribes can no longer access the land for food and medicine, WWF’s corporate partners are able to enter the region to access its natural resources. SI reports that, “WWF was partnering with seven companies logging nearly 4 million hectares of forests belonging to the Baka and Bayaka.”

Timber removed by these companies is sometimes dubbed “sustainable” through questionable methods by WWF, who is paid a fee for the certification. According to a report by Global Witness, WWF’s Global Forest and Trade Network has few standards for member companies that allows them to obtain wood from illegal sources or practice such destructive practices as clearcutting natural forests and replacing them with plantations.

In the rainforests of Sumatra, residents and their small rubber fields were evicted to create Tesso Nilo National Park. This allowed for the protection of the last 500 Sumatran tigers, while also enabling for the destruction of rainforest by firms such as Asia Pacific Resources International to make way for palm oil monocrop plantations for agribusiness giant Wilmar International, who then sold the product to such mega conglomerates as Unilever.

Despite the destruction of vital habitats and rainforest land, as well as the use of dangerous pesticides, these products can still be labelled as sustainable under the standards of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), whose board includes the WWF.

Meanwhile, agro-giants like Monsanto and Cargill participated in the WWF-led Round Table on Responsible Soy Association (RTRS) to greenwash the production of GMO soy. Der Spiegel details how RTRS soybeans are not guaranteed to be derived from non-GMO crops nor are they necessarily free from pesticides.

WWF also partners with mining companies, portioning off a section of nature for protection and leaving the rest for “sustainable” resource extraction. In Borneo, more than 23 million hectares of forest were to be managed by the WWF and three national governments. In 2012, 58 percent of the area covered with industrial operations: 9 percent for timber and palm oil plantations, 18 percent for mining and almost a third for logging concessions.

The WWF uses the same strategy of cordoning off land with hydroelectric dams: determining what land should be conserved and what is safe to sacrifice in favor of industry. Though the NGO participated in a campaign to prevent British oil company SOCO from drilling in Virunga National Park in the DRC, it subsequently participated in a survey with the Howard G. Buffett Foundation about the impact of four hydroelectric dams in the park.

Wilfred Huismann explains in his book, PandaLeaks, what the WWF gets in return for greenwashing these efforts: “The WWF is a willing service provider to the giants of the food and energy sectors, supplying industry with a green, progressive image. But ecological indulgences under the banner of the panda have their price: companies pay sizable license fees for using the WWF panda in their advertising and packaging. Big business presumably pays even higher sums to the WWF for studies conducted and consultation services rendered. Then there are the enormous individual donations from companies that collaborate with the WWF, in the RSPO or other capacities.”

These activities are in the process of coalescing under a new campaign, announced at the 2019 World Economic Forum, pinned to the urgency of climate change and ecological collapse. The WWF is part of a growing movement on the part of many of the world’s most powerful companies and business interests to sell off what remains of the planet with the claim that “Globalization 4.0 is an opportunity to save the planet and drive economic growth.”

The companies and business interests involved in this movement include such notables as Coca-Cola, Procter & Gamble (via Global Shapers), IKEA, Salesforce, Alcoa, Cargill, Citibank, Shell, the World Bank and the Rockefeller Foundation (via the World Resources Institute). The method of profiting features investing in carbon capture technology, carbon credits, electric vehicle infrastructure, and new financing methods similar to microloans.

With this context, the abuse allegations of WWF paramilitary units present a different picture. Much of the staff on the ground likely believes it’s doing meaningful work in the over 100 countries in which WWF operates and the NGO has been a prominent voice in such important environmental issues as global warming and nuclear energy.

As potentially beneficial as this work may be, it also provides a cover for more nefarious activity. In the least cohesive, piecemeal image of the details laid out here, you have the world’s largest conservation group associated with secrecy, corruption and the arming and training of violent paramilitary forces since at least the 1980s. A coherent narrative of the WWF’s history, however, is one in which the world’s power elite—world leaders, CEOs, and intelligence agents—leverage the WWF brand to remove indigenous groups from large sections of natural land, which is then used for eco-tourism, wildlife hunting, and staging military activities. This leaves the remaining land open for development by the world’s most powerful companies to build hydroelectric dams, cultivate palm oil plantations, sell carbon credits or cultivate genetically modified soy monocrops that receive a WWF mark of sustainability.

Not only is this important in the context of holding WWF accountable, but in addressing the world to come as business and governments adapt to climate change and social movements. If the Panda logo is taking advantage of concern for the environment in order to exploit it, chances are that there are other interests deploying a similar strategy for similar reasons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License. Feel free to republish with attribution to the author and share widely.

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.