From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

CCSF Chancellor Mark Rocha, Argosy University, for-profit school - History Of Corruption

CCSF Chancellor Mark Rocha has been involved in corruption and looting of colleges for many years. He is continuing his record with the destruction of San Francisco Community College

CCSF Chancellor Mark Rocha & Argosy University, a for-profit school - The History Of Corruption, Looting and Wrecking Public Education

Pasadena City College president Mark Rocha is leaving after rocky tenure

Rocha was hired in 2010 after a four-year stint at West Los Angeles College. He has also worked at Seton Hall and Argosy University, a for-profit school. School trustees voted to extend Rocha’s contract last year.

https://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-pcc-president-20140808-story.html

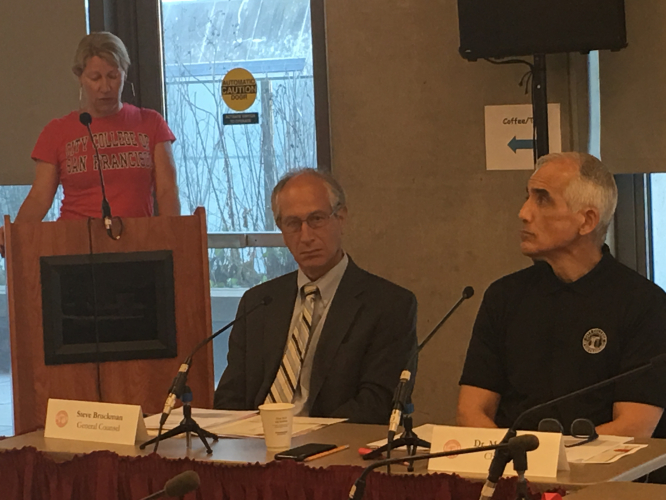

Pasadena City College President Mark Rocha, right, in 2012. Rocha retired in August. (Tim Berger / Pasadena Sun)

By JASON SONGWRITER

AUG. 7, 20147:31 PM

The controversial president of Pasadena City College will retire at the end of the month, officials announced Thursday.

Mark W. Rocha will step down from his nearly $250,000-a-year job at the end of August, according to a statement from the college. The trustees soon will hire an interim president, according to the statement from spokeswoman Valerie Wardlaw.

“It’s time for me to spend more time with my family and return to my passion for teaching and writing,” Rocha said in a statement.

He did not return a call seeking comment.

Rocha has been heavily criticized by some staff, who say he has ignored the school’s policy of consulting faculty on major decisions. Faculty leaders took two votes expressing no confidence in Rocha and were considering a third.

Tensions at the 26,000-student school were so high that a team of advisors visited the campus and told the administration and faculty that they needed to “find a way to move forward.”

Rocha was hired in 2010 after a four-year stint at West Los Angeles College. He has also worked at Seton Hall and Argosy University, a for-profit school. School trustees voted to extend Rocha’s contract last year.

Recently, Rocha was a finalist for the top job at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, but did not get the position.

Some trustees voiced support for Rocha, saying he had done a good job of leading the school during tough economic times, and they downplayed tensions between administrators and staff.

“There’s always turmoil,” said Board of Trustees President Anthony Fellow in a brief interview earlier this year.

In a statement, Fellow said the board accepted Rocha’s decision “with profound gratitude for his leadership over the past four years.”

Rocha and the trustees have also been criticized for canceling winter session two years ago. Students said that they would have a harder time earning credits to graduate or transfer without the six-week courses.

During Rocha’s tenure, full-time enrollment at the two-year college, long considered one of the state’s finest, dropped by nearly 13%, according to state statistics. Enrollment in California community colleges fell by nearly 10% during the same period.

Pasadena City College leadership also came under fire for inviting, and then uninviting, Oscar-winning alumnus Dustin Lance Black as commencement speaker. The invitation was rescinded over concerns about an illegally obtained sex video featuring the screenwriter, but trustees backed off and Black spoke at graduation.

In an anonymous online survey conducted by some faculty, the majority of respondents said Rocha had done a poor job leading the school.

“Fascist approach to leadership,” one wrote. “Rocha is destroying PCC,” said another.

jason.song [at] latimes.com

Twitter: @latjasonsong

Who’s Who In DeVos-Dream Center College Collapse?

https://www.republicreport.org/2019/whos-who-in-devos-dream-center-college-collapse/

POSTED AT 1:36 PM BY DAVID HALPERIN

With the Art Institutes, Argosy University, and South University chains of career colleges, and their operator Dream Center Education Holdings, in free fall, with students and staff in turmoil as campuses disintegrate or shut down, and with leading members of Congress demanding an investigation of the Betsy DeVos Department of Education’s role in the debacle, it’s an appropriate time to round up the major players — as someone once said, some that you recognize, some that you’ve hardly even heard of.

We hope this assembling of key actors in the DCEH drama — based on public records, internal documents, and interviews — will help those investigating and following the matter to understand what’s happened and who’s involved. (If we’re missing anyone, let us know at tips [at] republicreport.org.)

— EDMC’s Mark McEachen.

The final CEO of the troubled for-profit college chain Education Management Corp. (EDMC), McEachen took the helm just before the company, which had been receiving as much as $1.8 billion a year in taxpayer dollars, agreed to a $200 million-ish settlement of fraud charges with federal and state law enforcement. After EDMC, which engaged in deceptive and coercive recruiting and charged astronomical tuition, sold its schools to DCEH in 2017 and headed to bankruptcy, McEachen took a payout of more than $14 million, part of a $30 million parting gift for EDMC senior executives that was approved by the Betsy DeVos Department of Education. DCEH management claim that McEachen and his team, in negotiating the sale, presented them with deceptive information about the financial health of the schools.

— DCEH’s Brent Richardson.

As Republic Report has detailed in articles since last May, non-profit DCEH appeared to be seeking to leverage its operation of the former EDMC schools to provide revenue to for-profit schools — including the Steve Wozniak-branded coding camp Woz U — and other businesses tied to DCEH CEO Brent Richardson, his family members, and his long-time associates. In addition to this blatant but concealed-from-the-public conflict of interest, and other misdeeds, DCEH falsely told students that two of its schools remained accredited, when in fact its accreditor, Higher Learning Commissions, had suspended that status. Richardson, whose net worth is in the hundreds of millions, resigned as DCEH CEO last month, just before the company was placed in receivership by a federal court, and promptly showed up at Woz U, which he owns, to resume control there.

— The DCEH “Cabinet.”

Richardson’s hand-selected 12-member executive team to run the non-profit DCEH included six people who previously worked at for-profit Grand Canyon University, where Richardson was CEO, and at least three others who had worked at rival for-profit giants DeVry and University of Phoenix. The Cabinet members were: Brent Richardson, Chief Executive Officer; John Crowley, Chief Operating Officer; Chad Garrett, Chief Financial Officer; Monica Carson, Chief Enrollment Officer; Melissa Esbenshade, Chief Marketing Officer; Shelley Gardner, Chief Student Services Officer and wife of Richardson’s nephew; Mike Lacrosse, Chief Technology Officer; Shelly Murphy, Chief Regulatory and Government Affairs Officer; Rob Paul, Chief Strategic Initiatives Officer; Christopher Richardson, General Counsel and Secretary, and Brent’s brother; Debbi Lannon-Smith, Chief Human Resources Officer; and Stacy Sweeney, Chief Academic Excellence Officer.

— The DCEH Board of Managers.

Formed by the Los Angeles-headquartered, faith-oriented charity the Dream Center, DCEH created a board of Dream Center leaders and education executives. The board was charged with overseeing and approving Richardson’s moves, including his questionable plans to make business deals with for-profit entities he owned. The members: Brent Richardson, Co-Chairman; Randall K. Barton, a tax attorney and former chairman of the for-profit education business Significant Systems, Co-Chairman and Chief Development Officer; Rev. Matthew Barnett, co-Founder of the Los Angeles Dream Center; Timothy Slottow, former president of the for-profit University of Phoenix and former CFO of the University of Michigan; Rufus Glasper, Chancellor Emeritus of Maricopa Community College; and Jack DeBartolo, architect.

— The Monitor: Thomas Perrelli.

Formerly the third-ranking official in the Obama Justice Department, Perrelli was hired in 2015 by the state attorneys general to serve as monitor of their settlement with EDMC. As the purchaser of EDMC schools, DCEH inherited the obligation to be monitored by Perrelli, a partner at Jenner & Block in DC. But DCEH management bristled at the oversight and argued at times they were not subject to its strictures. Perrelli traveled to Phoenix last June to attend a DCEH compliance “summit,” after DCEH had fired some of the more diligent compliance officials who were holdovers from EDMC; Perrelli said little but took notes. Perrelli issued a scathing report documenting, through October 1, abuses under DCEH, most of which Republic Report had exposed last May. Expect an announcement soon from the attorneys general as to whether they will exercise their right under the settlement to extend Perrelli’s term as monitor another six months, through this summer.

— Department of Education: Betsy DeVos and Diane Auer Jones.

While overseeing the dismantlement of accountability rules for for-profit college operators, and allowing the sham conversion of several for-profit colleges to non-profit status, Trump education secretary DeVos and her top higher education official Diane Jones, a former for-profit college lobbyist, also have engaged in appalling mismanagement and malfeasance with respect to DCEH.

The DeVos Department blessed the DCEH purchase of EDMC schools and later gave tentative approval to treat the schools as non-profit, which would allow them to evade some regulations that apply only to for-profit schools. According to a source close to DCEH management, the Department officials directed DCEH to misstate its suspended accreditation status. DeVos’s team also changed a regulation to make it possible for some DCEH schools to have their accreditation restored retroactively. And it pushed DCEH to keep some campuses open, perhaps so the Department wouldn’t have to deal with the claims of students entitled to loan cancellation if their schools close.

Eventually, Jones soured on DCEH, narrowed Richardson’s access to capital, and finally turned the DeVos Department’s support away from DCEH and toward the investment firm Colbeck (see below) and related actors.

Trump appointee Wayne Johnson, regaining some influence after an earlier demotion, and career Department lawyer Steve Finley have been Jones’s key lieutenants in this effort.

While Jones and her team have engaged intensely with corporate executives and lawyers through various efforts to keep the DCEH schools afloat and taxpayer money flowing to them, they have provided almost no information to students and staff of DCEH schools or to the general public.

Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin (IL) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), chair of the House Appropriations Subcommittee that oversees the Department of Education, last week asked the Department’s inspector general late to investigate the Department’s handling of DCEH.

— The Debt Holder: Michael Lau.

Lau is the CEO of Candlewood Investment Group, a hedge fund that holds much of the DCEH schools’ debt. Anxious to get his money back ahead of others, Lau has lobbied Jones relentlessly, and eventually pushed Jones to favor Colbeck (see below) over DCEH. See also Gary Lee, below.

— Colbeck’s Jason Colodne and Jason Beckman.

Jasons Colodne and Beckman are the leaders of Colbeck Capital Management, a New York- and Los Angeles-based investment firm that focuses on making loans to corporations.

Last spring DCEH started talks with Colbeck about investing in the schools. In January, emails to staff from DCEH officials and a press release from something called the Education Principle Foundation (EPF) announced that EPF would be acquiring many of the Art Institutes campuses, as well as South University. At the same time, DCEH officials said that a company called Studio Enterprise would be hired to provide services to both the campuses being sold to EPF and those staying with DCEH. [Read: the Studio-DCEH framework agreement and EPF-DCEH purchase agreement.)

No one explained that Colbeck is behind both EPF and Studio; that was left for Republic Report to expose. Colbeck created the non-profit EPF, which until New Year’s Eve was called the Colbeck Foundation, and Colbeck is an investor in the for-profit Studio Enterprise. It’s not clear how Colbeck thought it was a good strategy to try to conceal this blatant conflict of interest.

Adding to the concerns here: A draft DCEH restructuring plan provided that Colbeck would offer DCEH’s management team the chance to “participate in the upside” of the Colbeck service contract. Translation: Officials of a non-profit educational organization, DCEH, were apparently negotiating, as part of the transfer of the organization’s assets, that they personally would get paid from the deal. To make it even worse, they would be paid mostly with the taxpayer dollars that make up most of the schools’ revenue.

The board of directors of the Education Principle Foundation, according it its IRS filings, have been Colodne, Beckman, and the two other top officials at Colbeck. But now, Republic Report has learned, EPF has a new board, consisting of New York corporate finance lawyer Robin van Bokhorst; New Yorker John D’Agostino, managing director of the fund governance firm DMS; and Los Angeles-based Andrew Florin-Smith, partner at the commercial real estate firm iBorrow. So, no longer the Colbeck management team, but another group of Wall Street types.

— Ohio Governor Mike DeWine.

Newly-elected Ohio governor Mike DeWine served as the state’s attorney general until January and has been engaged in discussions about Ohio’s Eastern Gateway Community College acquiring Argosy from DCEH. The deal that DCEH proposed with Gateway would provide for a for-profit company to provide capital for the deal and then get paid to provide services to Gateway, an arrangement that DCEH described as comparable to the 2017 Kaplan-Purdue deal (a deal that was, from the perspective of many student advocates, highly troubling).

— Higher Education Partners’ Michael Perik.

Perik is the CEO of Higher Education Partners, LLC, another education service company. Perik’s firm has worked for Ohio’s Eastern Gateway Community College to open new campuses, to help marketing, recruit, and enroll for online degrees, and to assist in designing online courses. In the original design of the Gateway-DCEH deal, Perik would get the servicing contract for Argosy after Eastern Gateway acquired it, and DCEH would get a piece of that action. DeVos’s team later insisted that the Eastern Gateway servicing contract, like the others, go to Colbeck, though Perik and others could get subcontracts.

— The Receiver: Mark Dottore.

There’s the monitor, and there’s also the receiver; it sounds like you’re setting up a home theater.

An experienced court-appointed receiver for financially distressed companies, Dottore had been engaged by DCEH and then was picked as the company’s receiver in a trumped-up lawsuit in federal court in Ohio. Receivership allows DCEH protection from its many creditors — such as landlords, law firms, and lead generation companies — while avoiding bankruptcy, which would automatically end its eligibility for the federal student grants and loans that represent most of its revenue. Needing to account for millions in missing money, Dottore has publicly accused Studio Enterprise of already taking a big cut of the federal money without providing any services.

The receiver’s most recent filing, today, with the Ohio federal court indicates he is trying to find a solution that will cause the DeVos Department to release funds to cover stipends for students at the DCEH schools:

To be clear: the money to pay the Student Stipends is not missing. Under DOE regulations, the receivership has to have on hand $13 million to advance to students, and then the DOE reimburses the receivership. Because the receivership never had sufficient resources to pay the Student Stipends, it could not advance the money; because the funds could not be advanced, the DOE regulations state that it is under no obligation to reimburse. To put it bluntly, the payment of the Student Stipends is stalled over a “chicken and egg” debate.

The DOE and Receiver have been in discussions since the Receiver’s appointment, and in earnest discussions since February 7, 2019, both looking for a way to rectify this matter for those who matter most, the students of these institutions owed these funds. The institutions, the Receiver and state and regulatory agencies are fielding hundreds of calls a day from students facing eviction, impacted by repossession, unable to pay childcare and unable to provide for their families as a result of these funds not being released….

UPDATE 02-22-19 6:00 pm: Dottore filed another report with the court today, stating in part, “It appears that amounts improperly requested by [DCEH] and then advanced by the United States Department of Education were not remitted to students…. it was used to pay their operating expenses.”

— The Accreditors.

DCEH’s challenges intensified as its accrediting agencies — notwithstanding DeVos and Jones’s decision to rehabilitate the nation’s most lax accreditor, ACICS — decided to get tough on DCEH schools. Three accreditors — Middle States Commission on Higher Education, Higher Learning Commission (HLC), and WASC — all suspended or threatened to withdraw approval of DCEH-operated campuses. As Executive Vice President for Legal and Governmental Affairs at HLC, Karen Solinski was involved in that accreditor demoting two Art Institutes campuses to unaccredited “candidate” status. DCEH responded by, as noted, misrepresenting its accreditation status to students — an action for which students have now sued DCEH. A source close to DCEH says Jones’ team directed DCEH to make the misrepresentation. DCEH also considered suing HLC, but put those plans on hold. Solinski has since left HLC.

— The Lawyers.

While the losers in the DCEH saga are taxpayers, faculty, staff, and above all, students, the biggest winner may be corporate lawyers. One insider to the endless negotiations estimated that legal fees might exceed a hundred million dollars when all is done. “Every pig has been at the trough,” this person said. I didn’t say that.

Here are some of the attorneys who have been involved:

Ronald Holt. DCEH’s chosen regulatory lawyer, Holt, according to monitor Perrelli’s report, emailed an Education Department official with the news that DCEH schools would delete from their website the disclosures to students that for-profit colleges must make under the gainful employment rule — even though the Department had not formally approved DCEH’s conversion to non-profit status.

Dennis Cariello. DCEH added Cariello to the legal team when its officials came to believe that the for-profit college industry veteran, who was involved in preparing DeVos for her 2017 confirmation hearing, would be able to smooth the way with Diane Jones and Wayne Johnson.

Leo Beus. DCEH hired veteran litigator Beus to plan a lawsuit against EDMC.

Mike Goldstein. A senior lawyer on Cooley LLP’s busy for-profit college team, Goldstein has represented debt-holder Candlewood in this matter, while another Cooley lawyer, Katherine Lee Carey (see below) has represented Colbeck’s Studio Enterprise.

Gary Lee. Co-chair of the finance department at mega law firm Morrison Foerster, Lee heads a huge team of lawyers at his firm working for Candlewood. Lee, along with other MoFo lawyers and lawyers from the firm of Carpenter & Lipps in Columbus, Ohio, successfully moved to intervene in the receivership case, representing something called Flagler Master Fund SPC Ltd, alongside lawyers from big firm Winston & Strawn and from Cleveland’s Thompson Hine, who represent U.S. Bank. According to their joint court filing, “Flagler Master Fund SPC Ltd. (“Flagler”) is an investment fund managed by Candlewood Investment Group, LP (“Candlewood”). Flagler is a secured lender under the Defendants’ secured Credit Agreement and a beneficiary of a Second Lien Guaranty and Second Lien Pledge and Security Agreement. U.S. Bank is the administrative agent and collateral agent under the Credit Agreement and a secured party and beneficiary of each of the Second Lien Guaranty and the Second Lien Pledge and Security Agreement. In the aggregate, more than $115 million in secured obligations remain outstanding under the Credit Agreement, the Second Lien Guaranty, and the Second Lien Pledge and Security Agreement.” Got that? Flagler Master Fund is incorporated in the sunny Cayman Islands.

John Altorelli. A former partner at the demised and disgraced corporate law Dewey & LeBoeuf, later at DLA Piper, and now at Aequum Law, LLC in New York, Altorelli has been Colbeck’s lead lawyer in this matter.

Katherine Lee Carey. Carey, another lawyer at Cooley, has been representing Studio on the deal.

Jeffrey Potash, Peter Schwartz, and Amy Wollensack. Three New York-based partners at the giant corporate firm Covington & Burling, Potash, Schwartz, and Wollensack head another big team of lawyers hired by Altorelli to work for Studio/Colbeck on the deal. Other Covington lawyers represent Studio in the receivership case.

Note: An earlier version of this article stated that Mike Goldstein of Cooley LLP has represented Studio Enterprise, in addition to representing Candlewood. Although another Cooley lawyer, Katherine Lee Carey, has represented Studio, and a source involved in the deal told me that Cooley sought clearance from the Department of Education to allow Goldstein to represent Studio, Goldstein tells me he has never represented Studio. Goldstein says that he and Carey “came upon the engagements entirely independently of each other and when we discovered the connection erected … an ‘ethical screen'” to separate their representations.

One Whistleblower Triggered Dream Center Demise, DeVos Debacle

https://www.republicreport.org/2019/one-whistleblower-triggered-dream-center-demise-devos-debacle/

POSTED AT 11:07 AM BY DAVID HALPERIN

It started with a message out of the blue, sent by “John Doe,” a Dream Center Education Holdings employee who was not yet ready to tell me his or her name. “I know you have reported extensively on for-profit institutions, including EDMC, its unethical activities, and disregard for staff,” the employee began a message to me in early April 2018, using an acronym for Education Management Corp., the Pittsburgh-based for-profit business that ran the career education schools the Art Institutes, Argosy University, and South University, before multiple law enforcement probes for deceiving students and defrauding taxpayers brought the company down.

Collapsed EDMC had agreed in March 2017 to sell the schools to a new subsidiary of the Los Angeles-headquartered, faith-oriented charity the Dream Center, and some Members of Congress and advocates (including me) had raised questions about the deal, about whether the new subsidiary, run by Brent Richardson, former CEO of for-profit Grand Canyon University, would operate the schools in a manner that truly served students.

But the new Trump administration had declared itself annoyed by Obama-era efforts to restrain supposed “innovation” in higher education, and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who staffed up her Department with former senior executives of for-profit colleges, gave an initial thumbs-up to the deal.

The schools, under DCEH, were in business, enrolling new students and aggressively advertising their new non-profit status, in a world where predatory recruiting and awful student outcomes had given for-profit colleges a bad name. They already were announcing new expansions, like a partnership with unaccredited coding school Woz U, whose figurehead was Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

The message I received that morning in April continued, “I am a longtime employee… who came as part of the sale to Dream Center Education Holdings. I and a colleague have deep knowledge of DCEH activity that is far more unethical, including violation of regulatory requirements, misrepresentation to students” and nepotism by top DCEH leaders.

“As you can surely understand, my identity must remain anonymous,” the employee continued. “If this is something you would like to know more about, I can be contacted at this address.”

It was something I wanted to know more about, and extensive engagement with this whistleblower and a colleague, who soon were willing to provide their names, led to more sources with inside information, to documents, and clues hiding in plain site on the Internet.

On May 16, 2018, I published here a lengthy article establishing, among other things, that:

— DCEH was lying to students, claiming its Illinois and Colorado Art Institutes campuses were accredited, when in fact their accreditor had suspended that status.

— DCEH was failing to comply with obligations to disclose information about its programs to students, as required by an Obama-era rule called gainful employment.

— Richardson and other top DCEH executives who were his relatives or long-time associates appeared to be seeking to leverage their control of the operation to make money for Woz U and a web of other for-profit ventures they owned or staffed.

On May 31, after speaking with six more DCEH employees in the wake of the first article, I published again, exposing that predatory practices and conflicts of interests had ramped up all across the DCEH network of schools. More insiders soon fueled numerous additional reports, with documents and leaked audio that offered more evidence of troubling behavior at DCEH and, also, within the DeVos Department of Education, which seemed to be going to great lengths to prop up the DCEH operation.

While I was the first to surface evidence of DCEH misconduct, employees also had been talking to the court-appointed lawyer tasked with monitoring the operation’s compliance with the $200 million agreements that settled fraud lawsuits brought against EDMC by the U.S. Justice Department and state attorneys general. The monitor’s public report eventually detailed a similar set of abuses.

The media, starting with reporter Daniel Moore of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, began writing about the accreditation deception and other problems at DCEH. Eventually the New York Times, Washington Post, Inside Higher Ed and numerous other outlets delved deep into the DCEH crisis.

Democrats in Congress — including senators Patty Murray (WA), Dick Durbin (IL), and Elizabeth Warren (MA) — began asking DeVos questions about DCEH and the Department of Education’s role in the debacle. After Democrats took over the House of Representatives in January 2019, committees led by Representatives Bobby Scott (VA) and Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL) began obtaining more evidence, including documents showing that the Department facilitated the accreditation deception. Democrats in both houses built a record suggesting that DeVos’s top education aide, ex-for-profit college executive Diane Auer Jones, had not told the truth about her knowledge of DCEH’s accreditation deception and her role in the process.

The non-profit law firm National Student Legal Defense Network, meanwhile, had filed lawsuits against DCEH and DeVos on behalf of former students, actions that put pressure on the Department of Education and led to the disclosure of still more information.

The results of all this digging have been dramatic: Dream Center Education Holdings abruptly announced in late 2018 that numerous campuses would close. DCEH collapsed, and Brent Richardson resigned. DeVos and Jones turned over most of the remaining schools to another new non-profit that, we first reported, has its own troubling, hidden ties to a for-profit operation. A court-appointed receiver for DCEH squabbled with the new owners, the Department and others, amid allegations of misused and missing money. DeVos and Jones found themselves on the ropes, facing congressional inquiries, hearings, and threats of subpoenas for refusing to testify or provide documents.

The state of Arizona, often seen as friendly to for-profit college interests, cited the Dream Center debacle in taking away the educational licenseof Woz U, whose board and investors included Brent Richardson, and the coding school stopped enrolling students.

And on Friday, under pressure from Congress and lawsuits, DeVos announced that some 1500 Illinois and Colorado Art Institutes students who were victims of the accreditation deception would get some of their loans cancelled and grant eligibility restored. But DeVos unjustly blamed the accreditor, not DCEH or the Department, for the harms to students, and she didn’t offer nearly enough to make these or other former students whole.

Indeed, there’s still a more lot wrong: Broke former students of EDMC/DCEH, and other for-profit schools across the country, are still making payments or facing aggressive bill collectors over loans for overpriced educations that did nothing for their careers. Betsy DeVos and Diane Jones are still in power despite their affronts to students and taxpayers. Brent Richardson, and former EDMC executives and investors like Jeffrey Leeds, are still really rich.

But Friday’s announcement was a step toward righting a wrong and helping some struggling Americans get back on their feet.

One way or another, the abuses and deceptions at DCEH, and inside the DeVos Department of Education, were going to be exposed; there was too much wrongdoing, shared with too many people, for the secrets to remain hidden. But it was a single courageous, ethical, determined whistleblower who started the process, showing the power that one individual, armed only with the truth, can wield.

A College Chain Crumbles, and Millions in Student Loan Cash Disappears

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/07/business/argosy-college-art-insititutes-south-university.html

Lauren Jackson, a first-year student at Argosy University, and her daughter, Brooklynn Franklin, in Chicago. “I didn’t want to go home and tell my baby that Mommy may not be a doctor,” she said.

Lauren Jackson, a first-year student at Argosy University, and her daughter, Brooklynn Franklin, in Chicago. “I didn’t want to go home and tell my baby that Mommy may not be a doctor,” she said.Credit...Taylor Glascock for The New York Times

By Stacy Cowley and Erica L. Green

March 7, 2019

When the Education Department approved a proposal by Dream Center, a Christian nonprofit with no experience in higher education, to buy a troubled chain of for-profit colleges, skeptics warned that the charity was unlikely to pull off the turnaround it promised.

What they didn’t foresee was just how quickly and catastrophically it would fail.

Barely a year after the takeover, dozens of Dream Center campuses are nearly out of money and may close as soon as Friday. More than a dozen others have been sold in the hope they can survive.

The affected schools — Argosy University, South University and the Art Institutes — have about 26,000 students in programs spanning associate degrees in dental hygiene and doctoral programs in law and psychology. Fourteen campuses, mostly Art Institute locations, have a new owner after a hastily arranged transfer involving private equity executives. More than 40 others are under the control of a court-appointed receiver who has accused school officials of trying to keep the doors open by taking millions of dollars earmarked for students.

The problems, arising amid the Trump administration’s broad efforts to deregulate the for-profit college industry, began almost immediately after Dream Center acquired the schools in 2017. The charity, started 25 years ago and affiliated with a Pentecostal megachurch in Los Angeles, has a nationwide network of outreach programs for problems like homelessness and domestic violence and said it planned to use the schools to fund its expansion.

Now its students — many with credits that cannot be easily transferred — are stuck in a meltdown. On Wednesday, members of the faculty at Argosy’s Chicago and Northern Virginia campuses told students that they had been fired and instructed to remove their belongings. In Phoenix, an unpaid landlord locked students out of their classrooms. In California, a dean advised students two months away from graduation not to invite family to attend from out of town.

“In less than a month, everything I have worked for the past three years has been taken from me,” said Jayne Kenney, who is pursuing her doctorate in clinical psychology at Argosy’s Chicago campus. “I am also conscious of the fact that what seems like the swift fall of an ax in less than one month has in reality been festering for years.”

The fall accelerated last week when the Education Department cut off federal student loan funds to Argosy after the court-appointed receiver said school officials had taken about $13 million owed to students at 22 campuses and used it for expenses like payroll. The students, who had borrowed extra money to cover things like rent and groceries, were forced to use food banks or skip classes for lack of bus fare.

Lauren Jackson, a single mother seeking a doctorate at the Illinois School of Professional Psychology, an Argosy school in Chicago, did not receive the roughly $10,000 she was due in January. She has been paying expenses for herself and her 6-year-old daughter with borrowed money and GoFundMe donations.

On Tuesday, after three months of not paying her rent, she received an eviction notice.

“I didn’t want to go home and tell my baby that Mommy may not be a doctor,” said Ms. Jackson, whose school could close Friday. “Now I don’t want to go home and tell her that we don’t have a home.”

Led by Secretary Betsy DeVos, the Education Department has reversed an Obama-era crackdown on troubled vocational and career schools and allowed new and less experienced entrants into the field.

Image“What seems like the swift fall of an ax in less than one month has in reality been festering for years,” said Jayne Kenney, a doctoral student at Argosy in Chicago.

“What seems like the swift fall of an ax in less than one month has in reality been festering for years,” said Jayne Kenney, a doctoral student at Argosy in Chicago.Credit...Taylor Glascock for The New York Times

“The industry was on its heels, but they’ve been given new life by the department under DeVos,” said Eileen Connor, the director of litigation at Harvard Law School’s Project on Predatory Student Lending.

Ms. DeVos, who invested in companies with ties to for-profit colleges before taking office, has made it an agency priority to unfetter for-profit schools by eliminating restrictions on them. She also allowed several for-profit schools to evade even those loosened rules by converting to nonprofits.

That’s what Dream Center wanted to do when it asked to buy the remains of Education Management Corporation.

Education Management, once the nation’s second-largest for-profit college operator, was struggling for survival after an investigation into its recruiting tactics resulted in a $200 million settlement in 2015. Despite those troubles, it had 65,000 students, and some of its schools maintained strong reputations.

Dream Center is connected to Angelus Temple, which was founded by Aimee Semple McPherson, a charismatic evangelist once portrayed by Faye Dunaway in a TV movie, “The Disappearance of Aimee.” It is affiliated with the Foursquare Church, an evangelical denomination with outposts in 146 countries.

Buying a chain of schools “aligns perfectly with our mission, which views education as a primary means of life transformation,” Randall Barton, the foundation’s managing director, said when Dream Center announced its plan.

But Dream Center had never run colleges. It hired a team including Brent Richardson, who worked on the conversion of Grand Canyon University to a nonprofit as its chairman, to lead the schools’ corporate parent, Dream Center Education Holdings. He stepped down in January.

Alarms were ringing from the moment the takeover was proposed. Dream Center’s effort to buy the failing ITT Technical Institutes schools had fallen apart after resistance from the Obama administration. When it asked to buy Education Management’s schools, consumer groups, members of Congress and some regional accreditors raised concerns.

But in late 2017, Ms. DeVos’s agency gave preliminary approval to Dream Center’s plan.

Almost immediately, the organization discovered the schools were in worse shape than expected, with aging facilities and outdated technology. The universities “were, on the whole, failing without hope for redemption,” the receiver wrote in a court filing last month.

Dream Center had anticipated a $30 million profit in its first year, Mr. Barton wrote in a recent legal filing. Instead, it was facing a $38 million loss.

And Dream Center showed little inclination to curb the tactics that got Education Management in trouble, like misleading students about their employment prospects. The executives it installed cultivated a high-pressure culture in which profit surpassed all other concerns, according to a report filed last year by Thomas J. Perrelli, the court-appointed monitor overseeing the schools’ compliance with their state settlements.

Image

Argosy University in Chicago. Dream Center, a nonprofit that bought Argosy and other schools, anticipated a $30 million profit in its first year. Instead, it was facing a $38 million loss.

Argosy University in Chicago. Dream Center, a nonprofit that bought Argosy and other schools, anticipated a $30 million profit in its first year. Instead, it was facing a $38 million loss.Credit...Taylor Glascock for The New York Times

By the end of 2018, Dream Center was facing eviction on at least nine campuses and owed creditors more than $40 million, and Education Department officials scrambled to plan for what looked like an imminent implosion.

“We know all too well that precipitous school closures are bad for everyone involved and leave too many students high and dry,” said Liz Hill, an agency spokeswoman. “Teams of people at the department have been working tirelessly on behalf of students — caught up in this situation through no fault of their own — with the singular goal in mind to ensure as many students as possible had options to complete their education.”

A Rapid Unraveling

The problems grew in mid-January when a creditor sued Dream Center Education Holdings over unpaid bills and asked a federal court to install a receiver to wind down the insolvent organization. Within a day, a federal judge appointed Mark Dottore, who was working with Dream Center as a paid consultant, as its receiver.

At a forum last month with students at Argosy University in Chicago, Mr. Dottore tried to calm an anxious crowd.

“We will make it until June, I can pretty much assure you of that,” Mr. Dottore said, according to a recording provided to The New York Times by a student. “By hook or by crook, I’m going to get us there.”

But on Wednesday, Mr. Dottore filed an emergency motion describing his plans to sell Argosy’s campuses, plus the South University and Art Institute campuses that haven’t been sold already. Any that didn’t have a buyer by Friday would close, he said.

Even as Argosy campuses prepared to close, a dean at the American School of Professional Psychology in Northern Virginia emailed students on Wednesday, imploring them to attend classes the rest of the week “if we are to save the semester.”

Scott Peck, a 50-year-old student there, left behind a six-figure salary in software and cashed out his 401(k) savings to pay for his doctorate. But he feels worse for his younger classmates.

“What’s so heartbreaking is to see what’s happening to these kids in their 20s, who are believing things they’re told by people that they trust,” he said.

Argosy was supposed to pay students the extra money they had borrowed, then seek reimbursement from the government. But Argosy reported that the money was paid out even though it wasn’t, Mr. Dottore wrote in court filings, and used the reimbursements for operating expenses instead.

A Dream Center spokeswoman did not respond to requests for comment on the fraud accusation.

While Argosy students have little hope of getting back money they paid out of pocket, the Education Department said the federal loan debt of affected students would be forgiven for this semester. If the schools close, students can seek help under a program covering school shutdowns.

Scott Peck, 50, left behind a six-figure salary in software sales and consulting and cashed out his 401(k) savings to pay for his doctorate in clinical psychology at an Argosy University school.

Scott Peck, 50, left behind a six-figure salary in software sales and consulting and cashed out his 401(k) savings to pay for his doctorate in clinical psychology at an Argosy University school.Credit...Greg Kahn for The New York Times

Not all of the Dream Center schools are under threat of an immediate shutdown. Some were recently shunted to a new owner in a deal partly orchestrated by the Education Department.

But the arrangement with Studio Enterprise, a Los Angeles company that provides support services for creative-industry training programs, raises its own questions. Studio is personally funded by the principals of Colbeck Capital Management, a New York private equity firm that set up the nonprofit owner.

Dream Center said in July that it would close more than 30 ailing campuses across all three chains, but a few months later it reached a deal with Studio to salvage some Art Institute locations.

As Dream Center’s problems mounted in December, the Education Department called an emergency meeting. Studio agreed to coordinate an acquisition of eight Art Institute campuses and, at least temporarily, six South University campuses.

To maintain their nonprofit status, the agreement gave Studio the right to pick a nonprofit to buy the schools. Colbeck Capital used a Delaware-based nonprofit it created five years ago, renaming it the Education Principle Foundation, according to a state filinguncovered by the Republic Report, a site that has closely trackedDream Center’s unraveling.

In mid-January, a news release informed the 15,000 students at 14 Arts Institute and South campuses that their schools were owned by a foundation that hadn’t existed three weeks earlier. Two people familiar with the foundation’s plans said it intended to spin the South campuses off under their own leadership.

Robin Von Bokhorst, listed in legal filings as the foundation’s president, did not respond to requests for comment.

Bryan Newman, Studio’s chief executive, said the Art Institute schools had been “ignored for years.”

“We’re coming in with the view that these schools need investment,” he said.

Consumer groups and lawmakers, however, are questioning the arrangement. Two Democrats in Congress have asked the Education Department’s inspector general to investigate the department’s role in the deal.

The fate of the schools in receivership is still being sorted out. The judge who appointed Mr. Dottore scheduled a hearing for Monday to determine if he should be removed. Creditors have complained about his close ties to Dream Center, and the judge wondered if Mr. Dottore was managing the situation in a way that did “more harm than good.”

Many students agree.

“The way they presented the receivership was that it would be beneficial to the students, but it’s actually been detrimental,” said Marina Awed, a student at an Argosy school in California, Western State College of Law, who was scheduled to graduate in two months. “It shouldn’t be this easy to defraud the Department of Education.”

A version of this article appears in print on March 8, 2019, Section A, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Thousands Tripped Up as a College Chain Sinks.

Pasadena City College president Mark Rocha is leaving after rocky tenure

Rocha was hired in 2010 after a four-year stint at West Los Angeles College. He has also worked at Seton Hall and Argosy University, a for-profit school. School trustees voted to extend Rocha’s contract last year.

https://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-pcc-president-20140808-story.html

Pasadena City College President Mark Rocha, right, in 2012. Rocha retired in August. (Tim Berger / Pasadena Sun)

By JASON SONGWRITER

AUG. 7, 20147:31 PM

The controversial president of Pasadena City College will retire at the end of the month, officials announced Thursday.

Mark W. Rocha will step down from his nearly $250,000-a-year job at the end of August, according to a statement from the college. The trustees soon will hire an interim president, according to the statement from spokeswoman Valerie Wardlaw.

“It’s time for me to spend more time with my family and return to my passion for teaching and writing,” Rocha said in a statement.

He did not return a call seeking comment.

Rocha has been heavily criticized by some staff, who say he has ignored the school’s policy of consulting faculty on major decisions. Faculty leaders took two votes expressing no confidence in Rocha and were considering a third.

Tensions at the 26,000-student school were so high that a team of advisors visited the campus and told the administration and faculty that they needed to “find a way to move forward.”

Rocha was hired in 2010 after a four-year stint at West Los Angeles College. He has also worked at Seton Hall and Argosy University, a for-profit school. School trustees voted to extend Rocha’s contract last year.

Recently, Rocha was a finalist for the top job at Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, but did not get the position.

Some trustees voiced support for Rocha, saying he had done a good job of leading the school during tough economic times, and they downplayed tensions between administrators and staff.

“There’s always turmoil,” said Board of Trustees President Anthony Fellow in a brief interview earlier this year.

In a statement, Fellow said the board accepted Rocha’s decision “with profound gratitude for his leadership over the past four years.”

Rocha and the trustees have also been criticized for canceling winter session two years ago. Students said that they would have a harder time earning credits to graduate or transfer without the six-week courses.

During Rocha’s tenure, full-time enrollment at the two-year college, long considered one of the state’s finest, dropped by nearly 13%, according to state statistics. Enrollment in California community colleges fell by nearly 10% during the same period.

Pasadena City College leadership also came under fire for inviting, and then uninviting, Oscar-winning alumnus Dustin Lance Black as commencement speaker. The invitation was rescinded over concerns about an illegally obtained sex video featuring the screenwriter, but trustees backed off and Black spoke at graduation.

In an anonymous online survey conducted by some faculty, the majority of respondents said Rocha had done a poor job leading the school.

“Fascist approach to leadership,” one wrote. “Rocha is destroying PCC,” said another.

jason.song [at] latimes.com

Twitter: @latjasonsong

Who’s Who In DeVos-Dream Center College Collapse?

https://www.republicreport.org/2019/whos-who-in-devos-dream-center-college-collapse/

POSTED AT 1:36 PM BY DAVID HALPERIN

With the Art Institutes, Argosy University, and South University chains of career colleges, and their operator Dream Center Education Holdings, in free fall, with students and staff in turmoil as campuses disintegrate or shut down, and with leading members of Congress demanding an investigation of the Betsy DeVos Department of Education’s role in the debacle, it’s an appropriate time to round up the major players — as someone once said, some that you recognize, some that you’ve hardly even heard of.

We hope this assembling of key actors in the DCEH drama — based on public records, internal documents, and interviews — will help those investigating and following the matter to understand what’s happened and who’s involved. (If we’re missing anyone, let us know at tips [at] republicreport.org.)

— EDMC’s Mark McEachen.

The final CEO of the troubled for-profit college chain Education Management Corp. (EDMC), McEachen took the helm just before the company, which had been receiving as much as $1.8 billion a year in taxpayer dollars, agreed to a $200 million-ish settlement of fraud charges with federal and state law enforcement. After EDMC, which engaged in deceptive and coercive recruiting and charged astronomical tuition, sold its schools to DCEH in 2017 and headed to bankruptcy, McEachen took a payout of more than $14 million, part of a $30 million parting gift for EDMC senior executives that was approved by the Betsy DeVos Department of Education. DCEH management claim that McEachen and his team, in negotiating the sale, presented them with deceptive information about the financial health of the schools.

— DCEH’s Brent Richardson.

As Republic Report has detailed in articles since last May, non-profit DCEH appeared to be seeking to leverage its operation of the former EDMC schools to provide revenue to for-profit schools — including the Steve Wozniak-branded coding camp Woz U — and other businesses tied to DCEH CEO Brent Richardson, his family members, and his long-time associates. In addition to this blatant but concealed-from-the-public conflict of interest, and other misdeeds, DCEH falsely told students that two of its schools remained accredited, when in fact its accreditor, Higher Learning Commissions, had suspended that status. Richardson, whose net worth is in the hundreds of millions, resigned as DCEH CEO last month, just before the company was placed in receivership by a federal court, and promptly showed up at Woz U, which he owns, to resume control there.

— The DCEH “Cabinet.”

Richardson’s hand-selected 12-member executive team to run the non-profit DCEH included six people who previously worked at for-profit Grand Canyon University, where Richardson was CEO, and at least three others who had worked at rival for-profit giants DeVry and University of Phoenix. The Cabinet members were: Brent Richardson, Chief Executive Officer; John Crowley, Chief Operating Officer; Chad Garrett, Chief Financial Officer; Monica Carson, Chief Enrollment Officer; Melissa Esbenshade, Chief Marketing Officer; Shelley Gardner, Chief Student Services Officer and wife of Richardson’s nephew; Mike Lacrosse, Chief Technology Officer; Shelly Murphy, Chief Regulatory and Government Affairs Officer; Rob Paul, Chief Strategic Initiatives Officer; Christopher Richardson, General Counsel and Secretary, and Brent’s brother; Debbi Lannon-Smith, Chief Human Resources Officer; and Stacy Sweeney, Chief Academic Excellence Officer.

— The DCEH Board of Managers.

Formed by the Los Angeles-headquartered, faith-oriented charity the Dream Center, DCEH created a board of Dream Center leaders and education executives. The board was charged with overseeing and approving Richardson’s moves, including his questionable plans to make business deals with for-profit entities he owned. The members: Brent Richardson, Co-Chairman; Randall K. Barton, a tax attorney and former chairman of the for-profit education business Significant Systems, Co-Chairman and Chief Development Officer; Rev. Matthew Barnett, co-Founder of the Los Angeles Dream Center; Timothy Slottow, former president of the for-profit University of Phoenix and former CFO of the University of Michigan; Rufus Glasper, Chancellor Emeritus of Maricopa Community College; and Jack DeBartolo, architect.

— The Monitor: Thomas Perrelli.

Formerly the third-ranking official in the Obama Justice Department, Perrelli was hired in 2015 by the state attorneys general to serve as monitor of their settlement with EDMC. As the purchaser of EDMC schools, DCEH inherited the obligation to be monitored by Perrelli, a partner at Jenner & Block in DC. But DCEH management bristled at the oversight and argued at times they were not subject to its strictures. Perrelli traveled to Phoenix last June to attend a DCEH compliance “summit,” after DCEH had fired some of the more diligent compliance officials who were holdovers from EDMC; Perrelli said little but took notes. Perrelli issued a scathing report documenting, through October 1, abuses under DCEH, most of which Republic Report had exposed last May. Expect an announcement soon from the attorneys general as to whether they will exercise their right under the settlement to extend Perrelli’s term as monitor another six months, through this summer.

— Department of Education: Betsy DeVos and Diane Auer Jones.

While overseeing the dismantlement of accountability rules for for-profit college operators, and allowing the sham conversion of several for-profit colleges to non-profit status, Trump education secretary DeVos and her top higher education official Diane Jones, a former for-profit college lobbyist, also have engaged in appalling mismanagement and malfeasance with respect to DCEH.

The DeVos Department blessed the DCEH purchase of EDMC schools and later gave tentative approval to treat the schools as non-profit, which would allow them to evade some regulations that apply only to for-profit schools. According to a source close to DCEH management, the Department officials directed DCEH to misstate its suspended accreditation status. DeVos’s team also changed a regulation to make it possible for some DCEH schools to have their accreditation restored retroactively. And it pushed DCEH to keep some campuses open, perhaps so the Department wouldn’t have to deal with the claims of students entitled to loan cancellation if their schools close.

Eventually, Jones soured on DCEH, narrowed Richardson’s access to capital, and finally turned the DeVos Department’s support away from DCEH and toward the investment firm Colbeck (see below) and related actors.

Trump appointee Wayne Johnson, regaining some influence after an earlier demotion, and career Department lawyer Steve Finley have been Jones’s key lieutenants in this effort.

While Jones and her team have engaged intensely with corporate executives and lawyers through various efforts to keep the DCEH schools afloat and taxpayer money flowing to them, they have provided almost no information to students and staff of DCEH schools or to the general public.

Senate Democratic Whip Dick Durbin (IL) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), chair of the House Appropriations Subcommittee that oversees the Department of Education, last week asked the Department’s inspector general late to investigate the Department’s handling of DCEH.

— The Debt Holder: Michael Lau.

Lau is the CEO of Candlewood Investment Group, a hedge fund that holds much of the DCEH schools’ debt. Anxious to get his money back ahead of others, Lau has lobbied Jones relentlessly, and eventually pushed Jones to favor Colbeck (see below) over DCEH. See also Gary Lee, below.

— Colbeck’s Jason Colodne and Jason Beckman.

Jasons Colodne and Beckman are the leaders of Colbeck Capital Management, a New York- and Los Angeles-based investment firm that focuses on making loans to corporations.

Last spring DCEH started talks with Colbeck about investing in the schools. In January, emails to staff from DCEH officials and a press release from something called the Education Principle Foundation (EPF) announced that EPF would be acquiring many of the Art Institutes campuses, as well as South University. At the same time, DCEH officials said that a company called Studio Enterprise would be hired to provide services to both the campuses being sold to EPF and those staying with DCEH. [Read: the Studio-DCEH framework agreement and EPF-DCEH purchase agreement.)

No one explained that Colbeck is behind both EPF and Studio; that was left for Republic Report to expose. Colbeck created the non-profit EPF, which until New Year’s Eve was called the Colbeck Foundation, and Colbeck is an investor in the for-profit Studio Enterprise. It’s not clear how Colbeck thought it was a good strategy to try to conceal this blatant conflict of interest.

Adding to the concerns here: A draft DCEH restructuring plan provided that Colbeck would offer DCEH’s management team the chance to “participate in the upside” of the Colbeck service contract. Translation: Officials of a non-profit educational organization, DCEH, were apparently negotiating, as part of the transfer of the organization’s assets, that they personally would get paid from the deal. To make it even worse, they would be paid mostly with the taxpayer dollars that make up most of the schools’ revenue.

The board of directors of the Education Principle Foundation, according it its IRS filings, have been Colodne, Beckman, and the two other top officials at Colbeck. But now, Republic Report has learned, EPF has a new board, consisting of New York corporate finance lawyer Robin van Bokhorst; New Yorker John D’Agostino, managing director of the fund governance firm DMS; and Los Angeles-based Andrew Florin-Smith, partner at the commercial real estate firm iBorrow. So, no longer the Colbeck management team, but another group of Wall Street types.

— Ohio Governor Mike DeWine.

Newly-elected Ohio governor Mike DeWine served as the state’s attorney general until January and has been engaged in discussions about Ohio’s Eastern Gateway Community College acquiring Argosy from DCEH. The deal that DCEH proposed with Gateway would provide for a for-profit company to provide capital for the deal and then get paid to provide services to Gateway, an arrangement that DCEH described as comparable to the 2017 Kaplan-Purdue deal (a deal that was, from the perspective of many student advocates, highly troubling).

— Higher Education Partners’ Michael Perik.

Perik is the CEO of Higher Education Partners, LLC, another education service company. Perik’s firm has worked for Ohio’s Eastern Gateway Community College to open new campuses, to help marketing, recruit, and enroll for online degrees, and to assist in designing online courses. In the original design of the Gateway-DCEH deal, Perik would get the servicing contract for Argosy after Eastern Gateway acquired it, and DCEH would get a piece of that action. DeVos’s team later insisted that the Eastern Gateway servicing contract, like the others, go to Colbeck, though Perik and others could get subcontracts.

— The Receiver: Mark Dottore.

There’s the monitor, and there’s also the receiver; it sounds like you’re setting up a home theater.

An experienced court-appointed receiver for financially distressed companies, Dottore had been engaged by DCEH and then was picked as the company’s receiver in a trumped-up lawsuit in federal court in Ohio. Receivership allows DCEH protection from its many creditors — such as landlords, law firms, and lead generation companies — while avoiding bankruptcy, which would automatically end its eligibility for the federal student grants and loans that represent most of its revenue. Needing to account for millions in missing money, Dottore has publicly accused Studio Enterprise of already taking a big cut of the federal money without providing any services.

The receiver’s most recent filing, today, with the Ohio federal court indicates he is trying to find a solution that will cause the DeVos Department to release funds to cover stipends for students at the DCEH schools:

To be clear: the money to pay the Student Stipends is not missing. Under DOE regulations, the receivership has to have on hand $13 million to advance to students, and then the DOE reimburses the receivership. Because the receivership never had sufficient resources to pay the Student Stipends, it could not advance the money; because the funds could not be advanced, the DOE regulations state that it is under no obligation to reimburse. To put it bluntly, the payment of the Student Stipends is stalled over a “chicken and egg” debate.

The DOE and Receiver have been in discussions since the Receiver’s appointment, and in earnest discussions since February 7, 2019, both looking for a way to rectify this matter for those who matter most, the students of these institutions owed these funds. The institutions, the Receiver and state and regulatory agencies are fielding hundreds of calls a day from students facing eviction, impacted by repossession, unable to pay childcare and unable to provide for their families as a result of these funds not being released….

UPDATE 02-22-19 6:00 pm: Dottore filed another report with the court today, stating in part, “It appears that amounts improperly requested by [DCEH] and then advanced by the United States Department of Education were not remitted to students…. it was used to pay their operating expenses.”

— The Accreditors.

DCEH’s challenges intensified as its accrediting agencies — notwithstanding DeVos and Jones’s decision to rehabilitate the nation’s most lax accreditor, ACICS — decided to get tough on DCEH schools. Three accreditors — Middle States Commission on Higher Education, Higher Learning Commission (HLC), and WASC — all suspended or threatened to withdraw approval of DCEH-operated campuses. As Executive Vice President for Legal and Governmental Affairs at HLC, Karen Solinski was involved in that accreditor demoting two Art Institutes campuses to unaccredited “candidate” status. DCEH responded by, as noted, misrepresenting its accreditation status to students — an action for which students have now sued DCEH. A source close to DCEH says Jones’ team directed DCEH to make the misrepresentation. DCEH also considered suing HLC, but put those plans on hold. Solinski has since left HLC.

— The Lawyers.

While the losers in the DCEH saga are taxpayers, faculty, staff, and above all, students, the biggest winner may be corporate lawyers. One insider to the endless negotiations estimated that legal fees might exceed a hundred million dollars when all is done. “Every pig has been at the trough,” this person said. I didn’t say that.

Here are some of the attorneys who have been involved:

Ronald Holt. DCEH’s chosen regulatory lawyer, Holt, according to monitor Perrelli’s report, emailed an Education Department official with the news that DCEH schools would delete from their website the disclosures to students that for-profit colleges must make under the gainful employment rule — even though the Department had not formally approved DCEH’s conversion to non-profit status.

Dennis Cariello. DCEH added Cariello to the legal team when its officials came to believe that the for-profit college industry veteran, who was involved in preparing DeVos for her 2017 confirmation hearing, would be able to smooth the way with Diane Jones and Wayne Johnson.

Leo Beus. DCEH hired veteran litigator Beus to plan a lawsuit against EDMC.

Mike Goldstein. A senior lawyer on Cooley LLP’s busy for-profit college team, Goldstein has represented debt-holder Candlewood in this matter, while another Cooley lawyer, Katherine Lee Carey (see below) has represented Colbeck’s Studio Enterprise.

Gary Lee. Co-chair of the finance department at mega law firm Morrison Foerster, Lee heads a huge team of lawyers at his firm working for Candlewood. Lee, along with other MoFo lawyers and lawyers from the firm of Carpenter & Lipps in Columbus, Ohio, successfully moved to intervene in the receivership case, representing something called Flagler Master Fund SPC Ltd, alongside lawyers from big firm Winston & Strawn and from Cleveland’s Thompson Hine, who represent U.S. Bank. According to their joint court filing, “Flagler Master Fund SPC Ltd. (“Flagler”) is an investment fund managed by Candlewood Investment Group, LP (“Candlewood”). Flagler is a secured lender under the Defendants’ secured Credit Agreement and a beneficiary of a Second Lien Guaranty and Second Lien Pledge and Security Agreement. U.S. Bank is the administrative agent and collateral agent under the Credit Agreement and a secured party and beneficiary of each of the Second Lien Guaranty and the Second Lien Pledge and Security Agreement. In the aggregate, more than $115 million in secured obligations remain outstanding under the Credit Agreement, the Second Lien Guaranty, and the Second Lien Pledge and Security Agreement.” Got that? Flagler Master Fund is incorporated in the sunny Cayman Islands.

John Altorelli. A former partner at the demised and disgraced corporate law Dewey & LeBoeuf, later at DLA Piper, and now at Aequum Law, LLC in New York, Altorelli has been Colbeck’s lead lawyer in this matter.

Katherine Lee Carey. Carey, another lawyer at Cooley, has been representing Studio on the deal.

Jeffrey Potash, Peter Schwartz, and Amy Wollensack. Three New York-based partners at the giant corporate firm Covington & Burling, Potash, Schwartz, and Wollensack head another big team of lawyers hired by Altorelli to work for Studio/Colbeck on the deal. Other Covington lawyers represent Studio in the receivership case.

Note: An earlier version of this article stated that Mike Goldstein of Cooley LLP has represented Studio Enterprise, in addition to representing Candlewood. Although another Cooley lawyer, Katherine Lee Carey, has represented Studio, and a source involved in the deal told me that Cooley sought clearance from the Department of Education to allow Goldstein to represent Studio, Goldstein tells me he has never represented Studio. Goldstein says that he and Carey “came upon the engagements entirely independently of each other and when we discovered the connection erected … an ‘ethical screen'” to separate their representations.

One Whistleblower Triggered Dream Center Demise, DeVos Debacle

https://www.republicreport.org/2019/one-whistleblower-triggered-dream-center-demise-devos-debacle/

POSTED AT 11:07 AM BY DAVID HALPERIN

It started with a message out of the blue, sent by “John Doe,” a Dream Center Education Holdings employee who was not yet ready to tell me his or her name. “I know you have reported extensively on for-profit institutions, including EDMC, its unethical activities, and disregard for staff,” the employee began a message to me in early April 2018, using an acronym for Education Management Corp., the Pittsburgh-based for-profit business that ran the career education schools the Art Institutes, Argosy University, and South University, before multiple law enforcement probes for deceiving students and defrauding taxpayers brought the company down.

Collapsed EDMC had agreed in March 2017 to sell the schools to a new subsidiary of the Los Angeles-headquartered, faith-oriented charity the Dream Center, and some Members of Congress and advocates (including me) had raised questions about the deal, about whether the new subsidiary, run by Brent Richardson, former CEO of for-profit Grand Canyon University, would operate the schools in a manner that truly served students.

But the new Trump administration had declared itself annoyed by Obama-era efforts to restrain supposed “innovation” in higher education, and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who staffed up her Department with former senior executives of for-profit colleges, gave an initial thumbs-up to the deal.

The schools, under DCEH, were in business, enrolling new students and aggressively advertising their new non-profit status, in a world where predatory recruiting and awful student outcomes had given for-profit colleges a bad name. They already were announcing new expansions, like a partnership with unaccredited coding school Woz U, whose figurehead was Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

The message I received that morning in April continued, “I am a longtime employee… who came as part of the sale to Dream Center Education Holdings. I and a colleague have deep knowledge of DCEH activity that is far more unethical, including violation of regulatory requirements, misrepresentation to students” and nepotism by top DCEH leaders.

“As you can surely understand, my identity must remain anonymous,” the employee continued. “If this is something you would like to know more about, I can be contacted at this address.”

It was something I wanted to know more about, and extensive engagement with this whistleblower and a colleague, who soon were willing to provide their names, led to more sources with inside information, to documents, and clues hiding in plain site on the Internet.

On May 16, 2018, I published here a lengthy article establishing, among other things, that:

— DCEH was lying to students, claiming its Illinois and Colorado Art Institutes campuses were accredited, when in fact their accreditor had suspended that status.

— DCEH was failing to comply with obligations to disclose information about its programs to students, as required by an Obama-era rule called gainful employment.

— Richardson and other top DCEH executives who were his relatives or long-time associates appeared to be seeking to leverage their control of the operation to make money for Woz U and a web of other for-profit ventures they owned or staffed.

On May 31, after speaking with six more DCEH employees in the wake of the first article, I published again, exposing that predatory practices and conflicts of interests had ramped up all across the DCEH network of schools. More insiders soon fueled numerous additional reports, with documents and leaked audio that offered more evidence of troubling behavior at DCEH and, also, within the DeVos Department of Education, which seemed to be going to great lengths to prop up the DCEH operation.

While I was the first to surface evidence of DCEH misconduct, employees also had been talking to the court-appointed lawyer tasked with monitoring the operation’s compliance with the $200 million agreements that settled fraud lawsuits brought against EDMC by the U.S. Justice Department and state attorneys general. The monitor’s public report eventually detailed a similar set of abuses.

The media, starting with reporter Daniel Moore of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, began writing about the accreditation deception and other problems at DCEH. Eventually the New York Times, Washington Post, Inside Higher Ed and numerous other outlets delved deep into the DCEH crisis.

Democrats in Congress — including senators Patty Murray (WA), Dick Durbin (IL), and Elizabeth Warren (MA) — began asking DeVos questions about DCEH and the Department of Education’s role in the debacle. After Democrats took over the House of Representatives in January 2019, committees led by Representatives Bobby Scott (VA) and Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL) began obtaining more evidence, including documents showing that the Department facilitated the accreditation deception. Democrats in both houses built a record suggesting that DeVos’s top education aide, ex-for-profit college executive Diane Auer Jones, had not told the truth about her knowledge of DCEH’s accreditation deception and her role in the process.

The non-profit law firm National Student Legal Defense Network, meanwhile, had filed lawsuits against DCEH and DeVos on behalf of former students, actions that put pressure on the Department of Education and led to the disclosure of still more information.

The results of all this digging have been dramatic: Dream Center Education Holdings abruptly announced in late 2018 that numerous campuses would close. DCEH collapsed, and Brent Richardson resigned. DeVos and Jones turned over most of the remaining schools to another new non-profit that, we first reported, has its own troubling, hidden ties to a for-profit operation. A court-appointed receiver for DCEH squabbled with the new owners, the Department and others, amid allegations of misused and missing money. DeVos and Jones found themselves on the ropes, facing congressional inquiries, hearings, and threats of subpoenas for refusing to testify or provide documents.

The state of Arizona, often seen as friendly to for-profit college interests, cited the Dream Center debacle in taking away the educational licenseof Woz U, whose board and investors included Brent Richardson, and the coding school stopped enrolling students.

And on Friday, under pressure from Congress and lawsuits, DeVos announced that some 1500 Illinois and Colorado Art Institutes students who were victims of the accreditation deception would get some of their loans cancelled and grant eligibility restored. But DeVos unjustly blamed the accreditor, not DCEH or the Department, for the harms to students, and she didn’t offer nearly enough to make these or other former students whole.

Indeed, there’s still a more lot wrong: Broke former students of EDMC/DCEH, and other for-profit schools across the country, are still making payments or facing aggressive bill collectors over loans for overpriced educations that did nothing for their careers. Betsy DeVos and Diane Jones are still in power despite their affronts to students and taxpayers. Brent Richardson, and former EDMC executives and investors like Jeffrey Leeds, are still really rich.

But Friday’s announcement was a step toward righting a wrong and helping some struggling Americans get back on their feet.

One way or another, the abuses and deceptions at DCEH, and inside the DeVos Department of Education, were going to be exposed; there was too much wrongdoing, shared with too many people, for the secrets to remain hidden. But it was a single courageous, ethical, determined whistleblower who started the process, showing the power that one individual, armed only with the truth, can wield.

A College Chain Crumbles, and Millions in Student Loan Cash Disappears

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/07/business/argosy-college-art-insititutes-south-university.html

Lauren Jackson, a first-year student at Argosy University, and her daughter, Brooklynn Franklin, in Chicago. “I didn’t want to go home and tell my baby that Mommy may not be a doctor,” she said.

Lauren Jackson, a first-year student at Argosy University, and her daughter, Brooklynn Franklin, in Chicago. “I didn’t want to go home and tell my baby that Mommy may not be a doctor,” she said.Credit...Taylor Glascock for The New York Times

By Stacy Cowley and Erica L. Green

March 7, 2019

When the Education Department approved a proposal by Dream Center, a Christian nonprofit with no experience in higher education, to buy a troubled chain of for-profit colleges, skeptics warned that the charity was unlikely to pull off the turnaround it promised.

What they didn’t foresee was just how quickly and catastrophically it would fail.

Barely a year after the takeover, dozens of Dream Center campuses are nearly out of money and may close as soon as Friday. More than a dozen others have been sold in the hope they can survive.

The affected schools — Argosy University, South University and the Art Institutes — have about 26,000 students in programs spanning associate degrees in dental hygiene and doctoral programs in law and psychology. Fourteen campuses, mostly Art Institute locations, have a new owner after a hastily arranged transfer involving private equity executives. More than 40 others are under the control of a court-appointed receiver who has accused school officials of trying to keep the doors open by taking millions of dollars earmarked for students.

The problems, arising amid the Trump administration’s broad efforts to deregulate the for-profit college industry, began almost immediately after Dream Center acquired the schools in 2017. The charity, started 25 years ago and affiliated with a Pentecostal megachurch in Los Angeles, has a nationwide network of outreach programs for problems like homelessness and domestic violence and said it planned to use the schools to fund its expansion.

Now its students — many with credits that cannot be easily transferred — are stuck in a meltdown. On Wednesday, members of the faculty at Argosy’s Chicago and Northern Virginia campuses told students that they had been fired and instructed to remove their belongings. In Phoenix, an unpaid landlord locked students out of their classrooms. In California, a dean advised students two months away from graduation not to invite family to attend from out of town.

“In less than a month, everything I have worked for the past three years has been taken from me,” said Jayne Kenney, who is pursuing her doctorate in clinical psychology at Argosy’s Chicago campus. “I am also conscious of the fact that what seems like the swift fall of an ax in less than one month has in reality been festering for years.”

The fall accelerated last week when the Education Department cut off federal student loan funds to Argosy after the court-appointed receiver said school officials had taken about $13 million owed to students at 22 campuses and used it for expenses like payroll. The students, who had borrowed extra money to cover things like rent and groceries, were forced to use food banks or skip classes for lack of bus fare.

Lauren Jackson, a single mother seeking a doctorate at the Illinois School of Professional Psychology, an Argosy school in Chicago, did not receive the roughly $10,000 she was due in January. She has been paying expenses for herself and her 6-year-old daughter with borrowed money and GoFundMe donations.

On Tuesday, after three months of not paying her rent, she received an eviction notice.

“I didn’t want to go home and tell my baby that Mommy may not be a doctor,” said Ms. Jackson, whose school could close Friday. “Now I don’t want to go home and tell her that we don’t have a home.”

Led by Secretary Betsy DeVos, the Education Department has reversed an Obama-era crackdown on troubled vocational and career schools and allowed new and less experienced entrants into the field.

Image“What seems like the swift fall of an ax in less than one month has in reality been festering for years,” said Jayne Kenney, a doctoral student at Argosy in Chicago.