From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Council Proposal Recognizes Lynching of Francisco Arias and José Chamales as 'Act of Racial Terror'

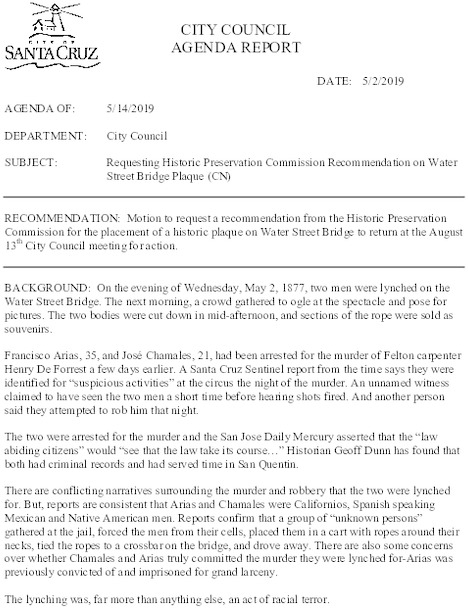

On May 14 the Santa Cruz City Council passed a motion to request a recommendation from the Historic Preservation Commission (for return to the August 13th City Council meeting for action) for the placement of a historic plaque on Water Street Bridge recognizing the lynching of Francisco Arias and José Chamales. The men, who were Californios, Spanish speaking Mexican and Native American men, were lynched on the bridge on May 2, 1877, shortly after their arrest on murder charges. "The lynching was, far more than anything else, an act of racial terror," wrote Councilmembers Sandy Brown, Drew Glover and Chris Krohn in their proposal submitted to council describing the need for the plaque. "Lacking recognition of this downtown lynching is a significant omission; this could be perceived by some as indicative of a wider reluctance to acknowledge our racial history," they wrote in the meeting's agenda report.

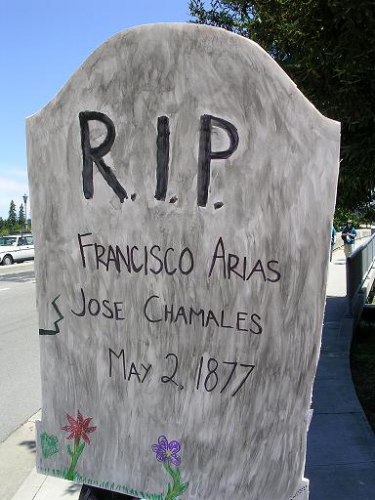

[Photo: Actions have been organized over the years to recognize the lynching. In 2005 a group of students spent their afternoon at the bridge to display a RIP sign and to distribute informational flyers. Cred., Josh Sonnenfeld: http://santacruz.indymedia.org/newswire/display/17862/index.php]

The agenda report for the May 14, 2019 Santa Cruz City Council meeting details some of the historical background of the lynching:

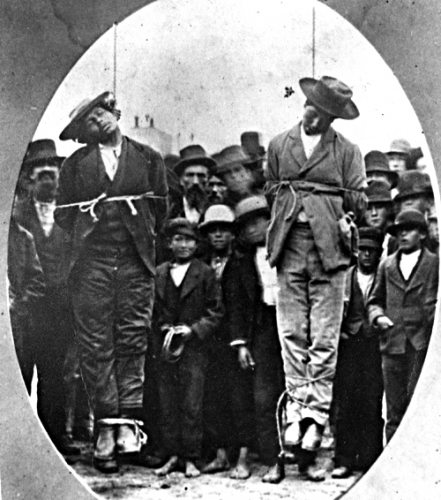

On the evening of Wednesday, May 2, 1877, two men were lynched on the Water Street Bridge. The next morning, a crowd gathered to ogle at the spectacle and pose for pictures. The two bodies were cut down in mid-afternoon, and sections of the rope were sold as souvenirs.

Francisco Arias, 35, and José Chamales, 21, had been arrested for the murder of Felton carpenter Henry De Forrest a few days earlier. A Santa Cruz Sentinel report from the time says they were identified for “suspicious activities” at the circus the night of the murder. An unnamed witness claimed to have seen the two men a short time before hearing shots fired. And another person said they attempted to rob him that night.

The two were arrested for the murder and the San Jose Daily Mercury asserted that the “law abiding citizens” would “see that the law take its course…” Historian Geoff Dunn has found that both had criminal records and had served time in San Quentin.

There are conflicting narratives surrounding the murder and robbery that the two were lynched for. But, reports are consistent that Arias and Chamales were Californios, Spanish speaking Mexican and Native American men. Reports confirm that a group of “unknown persons” gathered at the jail, forced the men from their cells, placed them in a cart with ropes around their necks, tied the ropes to a crossbar on the bridge, and drove away. There are also some concerns over whether Chamales and Arias truly committed the murder they were lynched for-Arias was previously convicted of and imprisoned for grand larceny.

The lynching was, far more than anything else, an act of racial terror.

This event is an important part of Santa Cruz’s history, and lacking recognition of this downtown lynching is a significant omission; this could be perceived by some as indicative of a wider reluctance to acknowledge our racial history. The lynching has been researched and written about by local historians Geoff Dunn and Sandy Lydon, but it still lacks wider public recognition.

As for the specific plaque, there has been a suggestion of including the image of the lynched men. Some feel this could be upsetting, but leaving it out undermines the meaning of a historical marker of this nature.

The language on the proposed marker is can be determined by a focus group of individuals comprised of local students, historians, alongside Latinx community members and people of color.

Requesting a recommendation from the Historic Preservation Commission should have no fiscal impact. Funding for the plaque can be generated through fundraising efforts described by the students and community members that brought this issue forward.

SUGGESTED READING:

Bellesiles, Michael A. 1877 : America’s Year of Living Violently New York: New Press,

2010.

Bellesiles explores the various acts of racial terror committed across America in the year of 1877. This time, almost a decade after the end of the Civil War, was one of economic growth in most of the United States. This did nothing to assuage racial tensions, and people of color throughout the country faced a daily threat.

Boener, Heather. “No Lynching signs meant to inform people of sad history.” Santa Cruz Sentinel November 30, 2000.

In 2000, UCSC art student set up an installation on the Water Street bridge in the form of signs that read,”No Lynching, Including nights, weekends, and holidays.” Alex Cabunoc did not receive permission from the city council to do this. This is an example of one of the few attempts made to publicly acknowledge this event. The article was published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel and is available in the online archive Newsbank.

Carrigan, William D., and Webb, Clive. Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848-1928. Cary: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, 2013. Accessed March 10, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central.

This book, published in 2013, is a detailed analysis of the way that violence against members of the Chicanx community goes unrecognized. The thousands of lynched Mexicans, overlooked by historians and activists alike, make up the “Forgotten Dead.”

Dunn, Geoffrey. Santa Cruz is in the Heart : Selected Writings on Local History, Culture, Politics & Ghosts Capitola, Calif: Capitola Book Company, 1989. Published in the late eighties, Geoffrey Dunn’s Santa Cruz is in the Heart remains a keystone of the study of Santa Cruz History. The book is available at the Santa Cruz Public Library.

Dunn, Geoffrey. "Santa Cruz's Most Notorious Lynching." SantaCruz.com. November 12, 2013. Accessed March 11, 2019.

https://www.santacruz.com/news/santa_cruzs_most_notorious_lynching.html

This edited excerpt from Santa Cruz is in the Heart is probably the reason that many people know of this event. It contains a composite narrative, drawn from articles published in various newspapers at the time.

Gonzales-Day, Ken. Lynching in the West: 1850-1935. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Historian Ken Gonzales-Day explores the ways that mob lynchings have shaped racial politics in California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Kulczyk, David. California Justice: Shootouts, Lynchings and Assassinations in the Golden State. Sanger, CA: World Dancer Press, 2008.

In an account similar to the one written by Bellesiles, Kulczyk explores the ways that white Californians enacted racial terror.

Romero, Simon. "Lynch Mobs Killed Latinos Across the West. The Fight to Remember These Atrocities Is Just Starting." The New York Times, March 2, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/us/porvenir-massacre-texasmexicans.

This article, published on the 2nd of this month, details the ways in which forgotten lynched latinos are only now being remembered and memorialized. This is a signifier of what could be a nationwide movement towards recognition of racism against the latinx population.

Unknown Author. "Murder-Arrest-Strangulation." The Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 3, 1877. Accessed March 10, 2019.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/4149963/francisco_arias_jose_chamales_lynching/.

This article is the first written about the event, two days after it happened. It includes one of the many disputed narratives. The article is available on microfilm in the genealogy section of the Santa Cruz Public Library, as well as on Newspapers.com.

Yamane, Linda. A Gathering of Voices The Native Peoples of the Central California Coast - Santa Cruz County History Journal # 5. Vol. 5. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum of Art and History, 2002.

Ohlone artist, performer, and scholar Linda Yamane has collected oral histories, writings, poems, and illustrations from Ohlone and other indigenous people. It includes poems and accounts of the lynching, as the two men were part Native American.

The agenda report for the May 14, 2019 Santa Cruz City Council meeting details some of the historical background of the lynching:

On the evening of Wednesday, May 2, 1877, two men were lynched on the Water Street Bridge. The next morning, a crowd gathered to ogle at the spectacle and pose for pictures. The two bodies were cut down in mid-afternoon, and sections of the rope were sold as souvenirs.

Francisco Arias, 35, and José Chamales, 21, had been arrested for the murder of Felton carpenter Henry De Forrest a few days earlier. A Santa Cruz Sentinel report from the time says they were identified for “suspicious activities” at the circus the night of the murder. An unnamed witness claimed to have seen the two men a short time before hearing shots fired. And another person said they attempted to rob him that night.

The two were arrested for the murder and the San Jose Daily Mercury asserted that the “law abiding citizens” would “see that the law take its course…” Historian Geoff Dunn has found that both had criminal records and had served time in San Quentin.

There are conflicting narratives surrounding the murder and robbery that the two were lynched for. But, reports are consistent that Arias and Chamales were Californios, Spanish speaking Mexican and Native American men. Reports confirm that a group of “unknown persons” gathered at the jail, forced the men from their cells, placed them in a cart with ropes around their necks, tied the ropes to a crossbar on the bridge, and drove away. There are also some concerns over whether Chamales and Arias truly committed the murder they were lynched for-Arias was previously convicted of and imprisoned for grand larceny.

The lynching was, far more than anything else, an act of racial terror.

This event is an important part of Santa Cruz’s history, and lacking recognition of this downtown lynching is a significant omission; this could be perceived by some as indicative of a wider reluctance to acknowledge our racial history. The lynching has been researched and written about by local historians Geoff Dunn and Sandy Lydon, but it still lacks wider public recognition.

As for the specific plaque, there has been a suggestion of including the image of the lynched men. Some feel this could be upsetting, but leaving it out undermines the meaning of a historical marker of this nature.

The language on the proposed marker is can be determined by a focus group of individuals comprised of local students, historians, alongside Latinx community members and people of color.

Requesting a recommendation from the Historic Preservation Commission should have no fiscal impact. Funding for the plaque can be generated through fundraising efforts described by the students and community members that brought this issue forward.

SUGGESTED READING:

Bellesiles, Michael A. 1877 : America’s Year of Living Violently New York: New Press,

2010.

Bellesiles explores the various acts of racial terror committed across America in the year of 1877. This time, almost a decade after the end of the Civil War, was one of economic growth in most of the United States. This did nothing to assuage racial tensions, and people of color throughout the country faced a daily threat.

Boener, Heather. “No Lynching signs meant to inform people of sad history.” Santa Cruz Sentinel November 30, 2000.

In 2000, UCSC art student set up an installation on the Water Street bridge in the form of signs that read,”No Lynching, Including nights, weekends, and holidays.” Alex Cabunoc did not receive permission from the city council to do this. This is an example of one of the few attempts made to publicly acknowledge this event. The article was published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel and is available in the online archive Newsbank.

Carrigan, William D., and Webb, Clive. Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848-1928. Cary: Oxford University Press USA - OSO, 2013. Accessed March 10, 2019. ProQuest Ebook Central.

This book, published in 2013, is a detailed analysis of the way that violence against members of the Chicanx community goes unrecognized. The thousands of lynched Mexicans, overlooked by historians and activists alike, make up the “Forgotten Dead.”

Dunn, Geoffrey. Santa Cruz is in the Heart : Selected Writings on Local History, Culture, Politics & Ghosts Capitola, Calif: Capitola Book Company, 1989. Published in the late eighties, Geoffrey Dunn’s Santa Cruz is in the Heart remains a keystone of the study of Santa Cruz History. The book is available at the Santa Cruz Public Library.

Dunn, Geoffrey. "Santa Cruz's Most Notorious Lynching." SantaCruz.com. November 12, 2013. Accessed March 11, 2019.

https://www.santacruz.com/news/santa_cruzs_most_notorious_lynching.html

This edited excerpt from Santa Cruz is in the Heart is probably the reason that many people know of this event. It contains a composite narrative, drawn from articles published in various newspapers at the time.

Gonzales-Day, Ken. Lynching in the West: 1850-1935. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

Historian Ken Gonzales-Day explores the ways that mob lynchings have shaped racial politics in California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Kulczyk, David. California Justice: Shootouts, Lynchings and Assassinations in the Golden State. Sanger, CA: World Dancer Press, 2008.

In an account similar to the one written by Bellesiles, Kulczyk explores the ways that white Californians enacted racial terror.

Romero, Simon. "Lynch Mobs Killed Latinos Across the West. The Fight to Remember These Atrocities Is Just Starting." The New York Times, March 2, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/02/us/porvenir-massacre-texasmexicans.

This article, published on the 2nd of this month, details the ways in which forgotten lynched latinos are only now being remembered and memorialized. This is a signifier of what could be a nationwide movement towards recognition of racism against the latinx population.

Unknown Author. "Murder-Arrest-Strangulation." The Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 3, 1877. Accessed March 10, 2019.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/4149963/francisco_arias_jose_chamales_lynching/.

This article is the first written about the event, two days after it happened. It includes one of the many disputed narratives. The article is available on microfilm in the genealogy section of the Santa Cruz Public Library, as well as on Newspapers.com.

Yamane, Linda. A Gathering of Voices The Native Peoples of the Central California Coast - Santa Cruz County History Journal # 5. Vol. 5. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum of Art and History, 2002.

Ohlone artist, performer, and scholar Linda Yamane has collected oral histories, writings, poems, and illustrations from Ohlone and other indigenous people. It includes poems and accounts of the lynching, as the two men were part Native American.

Add Your Comments

Latest Comments

Listed below are the latest comments about this post.

These comments are submitted anonymously by website visitors.

TITLE

AUTHOR

DATE

Revisionist history for Murderers

Mon, Sep 2, 2019 12:13AM

history

Sun, Aug 25, 2019 4:48AM

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network