Speakeasies and Artists Warehouses: A Tale of Two Oaklands

Dozens of reporters, videographers and photographers thronged around the yellow tape surrounding the block containing the Ghost Ship warehouse the morning after the tragic fire that killed 36 people in the center of Fruitvale. As the hour approached noon, a group of thousands of Latino Catholics began their scheduled annual procession for the Virgen de Guadalupe from St. Elizabeth’s Church, one of the largest Latino Catholic parishes in the Bay Area, located just three short blocks away. Their normal route for the yearly march from the church to the Diocese headquarters in downtown Oakland is down the length of International Boulevard until it rebounds off of Lake Merritt.

But on that morning, the procession was forced to reroute to 12th street, as the city of Oakland had shut down International Blvd for the three square blocks from Fruitvale to Derby St. The procession seemed never-ending, and the street was teeming, dozens of people per square foot. They were all Latinos, as of course, St. Elizabeth’s is a Latino church and cultural institution in the neighborhood. Sunday, the day after the fire, is always a big community day around the church, where even during a normal service, the crowd is standing room only, with even the vestibules of the church full of parishioners.

Wave after wave of the procession curved around the yellow hazard tape, and on to 12 th st., but journalists and photographers alike seemed non-plussed at the spectacle. Nothing about the procession, neither its existence, its character, the juxtaposition with the disaster or—most importantly—the fact that thousands of community members were right there available for the extraction of comment or opinion, attracted the attention of the media.

The Caminata de la Virgen de Guadalupe, an annual event of St. Elizabeth’s Church, snakes past the police cordon of the Ghost Ship fire on Sunday, December 3, 2016.

This attitude toward the neighborhood around the Ghost Ship and its Brown and Black population would echo throughout the discourse about the fire for weeks to come. Voices in Fruitvale, a neighborhood where almost half the children live in poverty, weren’t heard for days at all. In this sensational story that garnered nation-wide attention, it was weeks before journalists evinced the slightest interest in the neighborhood where the fire occurred.

For over a week after the fire, the city kept the section of International boulevard around the burnt out building closed off. In the first few days, as damage assessment and recovery operations occurred, this seemed like a reasonable and necessary decision, especially in view of how critical it was to provide information for the families involved. But long after there was any legitimate excuse, the city kept the street—a main artery for the busy neighborhood—closed because it was where it had set up its public relations stage.

City, police and fire officials positioned themselves on the stage in front of cameras and reporters, so that the burned out site and block could be visible in the background as fire and city officials gave their updates and speeches. This area was also reserved for the nation’s mobile satellite link trailers, news van and reporter parking. The official media pen became a fixture of the blockade for its duration of ten days, blocking off access to residences and businesses alike, as well as the local low-income clinic, Native American Health Center, which had to relocate its operations for the entire period to an adjacent building.

Media vehicles and satellite trucks parked in the penned off area around International Boulevard, mostly used as a parking lot and media stage for the fire spectacle.

Certainly, none of these things may have been more worthy of reporting than the unfolding details of the awful disaster that engulfed the off the books night club and residence at Ghost Ship. But the early establishment of an almost contemptuous disinterest in the actual denizens of the neighborhood became the template for the subsequent politicization of the disaster, and it was not one that was easily changed in later iterations.

After the initial shock of the fire, the deadliest in the United States in over a decade, and in Oakland’s history, the media and social media sphere began to craft its narrative. Not surprisingly, this was characterized in the normative whodunnit story that news media excels at. There was not much doubt that the fire’s deadly caste was in large part due to negligence and misguided internal construction, and local and national media wasted no time in pointing the finger at the warehouse’s master tenant, who had altered and decorated the space in an unsafe manner for a music venue.

No doubt, whatever the fault of the master tenant, the exploitative digging into every aspect of the family’s life was foul and uncalled for; it also obscured subsequent and relevant reporting into the city’s Potemkin fire and building departments. Indeed, some of the best reporting focused on the hobbling of normative city services in order to continue inflating the Oakland police department’s budget.

Again, lost within gumshoeing and finger-pointing was another issue, an open secret in Oakland. The city had years earlier hitched its call to gentrification to the very warehouse scene the Ghost Ship was said to be a part of. The building-code blind-eye policy to warehouses and artists and performance spaces was in large part responsible for the accelerated gentrification of Oakland’s uptown area, and the subsequently enfranchised sideshow known as first fridays, which became a major draw for higher income people into Oakland. This was not lost on Libby Schaaf who based her mayoral campaign on being part of Oakland’s hip underground art and entertainment scene. One need look no further than Schaaf’s coronation ceremony, where she rode in on a fire-spitting snail art car. The snail car’s fabricator, Jon Sarriugarte, seemed to think that Schaaf was a friend of the warehouse-living artist community:

One of the reasons Sarriugarte is such a fan of the mayor, he said, is because of her pledge to reinforce Oakland’s burgeoning community of artists and “makers.” “We have a wonderful maker community,” he said. “I want to see industrial areas set aside for making and producing things … [Schaaf] is really good at taking feedback from the community.”

Schaaf fashioned her public persona both before and after the campaign as one extremely focused on the indie and DIY arts scene in Oakland. Schaaf held her inaugural festivities at American Steel. Later, she convened the Artist Housing and Workspace Taskforce in 2015, with a mandate to explore methods of keeping Oakland affordable for artists including the city’s purchase of housing in land trust specifically for self-identified artists.

The fact that many live-work warehouses and commercial buildings are running unpermitted businesses, such as fabrication, sex-work venues and night clubs, never created a roadblock to Schaaf’s lucrative support of this scene. Those practices were considered an established right by the city and Oakland’s artist community alike. In this environment, there were no proscriptions against live-work or off the grid venues, quite the opposite. Indeed, one police report that emerged after the Ghost Ship fire described an OPD officer who responded to neighbor’s complaints of noise being turned away by the doorman and simply leaving.

Its worth noting that self-proclaimed artists are not the only people seeking to run unpermitted, illegal “culture-based” businesses in disused converted warehouses and storefronts. Just days ago, the Alameda County Sheriff sent a SWAT team to arrest and evict several people who had been living and working in a storefront, according to the sheriff-story—running an off the books gambling, and possible sex work venue in East Oakland, a couple of miles from the site of the Ghost Ship. Despite authority’s invocation of the Ghost Ship as the predicate for the raid, its clear that quick, decisive violent, carceral action was the boilerplate response by law enforcement for Oakland’s “other” live-work spaces for years.

Two years ago, for example, several blocks from the Ghostship in the dubs area of International Blvd, an underground storefront speakeasy was shut down shortly after it began operating because police believed that illegal gambling and possible prostitution were going on inside. Another illegal gambling spot—described by law enforcement as a casino–was shut down not far from Fruitvale BART on a similar pretext not long after, scant months after it began operating. The zero tolerance for such venues in Oakland is well-known, as is the criminalization and violent response to them, as opposed to the light touch and blind-eye for literally the same, at worst, misdemeanor acts by their white warehouse counterparts.

The only differences here, between the kinds of upper class “sex work”, drug use and other illegal activities that regularly take place in Oakland’s live-work spaces, and those that were summarily busted within months of beginning in the other, is quite clearly the race and social standing of the producers. This is the environment in which artists claimed a fraternity of victimhood beneath the bootheel of Libby Schaaf.

Not surprisingly, despite dozens of anecdotal tales of artists suddenly being evicted from their spaces by the city, it became clear after a few weeks that the only venue space red-tagged by the city was the Black-run Qilombo, which was not a live-work space at all, but a cultural center and community garden located at the edge of a gentrifying West Oakland. The die was already cast, however. The narrative of a community of embattled warehouse residents facing stringent and unfair enforcement of code became the dominant legacy of the Ghost Ship fire, politicizing the tragedy and the mourning that followed in ways that in hindsight, make little sense.

The Ghost Ship was an atypical live-work space, crammed from top to bottom with extremely unsafe fixtures and decorations. It was a functional nightclub with well-publicized shows that drew tourists and others from all around the Bay Area. As many observed given its regular use as a public venue for profit; the lack of exits; the large amount of flammable material, and bad management, Ghost Ship was a tragedy waiting to happen. More importantly, it was uniquely dangerous in the context of Oakland’s off the books venue scene, and it had a top-down structure that had very little resemblance to the typical live work or underground performance venue.

As the narrative about Ghost Ship grew, both in media and social media, three of its significant tropes became immutable. The first, and perhaps most key, was the definition of the affected community. This community was rarely defined in geographic terms, i.e., the adjacent brick and mortar businesses, and dwellings and people who lived and worked in them—working class and poor Latino and Black people with long-standing cultural roots in the community. Rather, the community affected by the Ghost Ship fire was an ephemeral and amorphous one, typically populated by white newcomers to Oakland—many from affluent or middle class backgrounds. Next came twin mythologies around warehouses themselves. One that artists and warehouse residents seem to buy into was that warehouses are dangerous places that need to be rehabilitated. The second, that this same group purported to fear as a consequence, was that the city, with its imagined historic antagonism to warehouse spaces, was now coming for them with a vengeance.

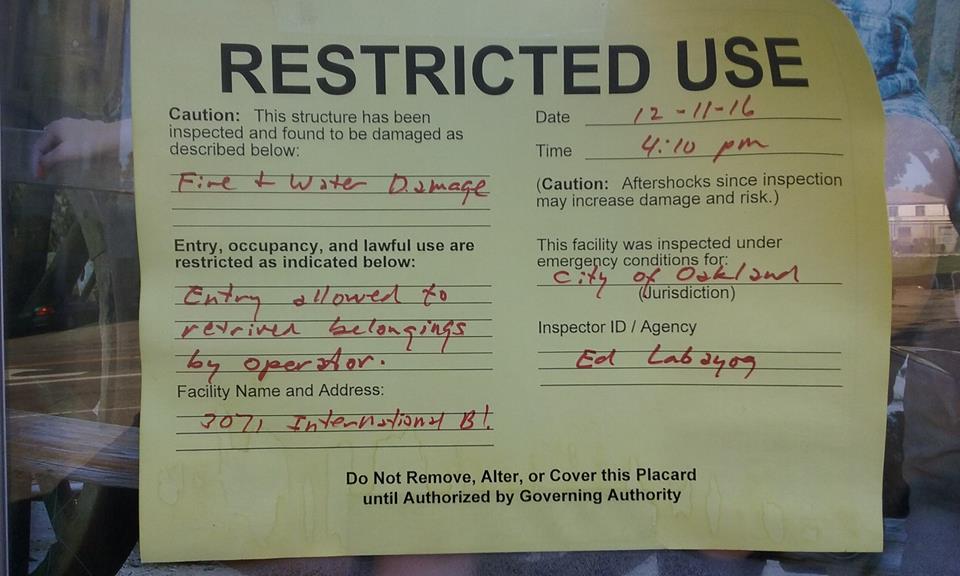

The twin beliefs of this floating community spawned several fundraisers to increase safety in existing live-work spaces, and to bring sites up to code for the coming storm of enforcement. It’s no exaggeration that the welfare of the physical community that Ghost Ship fire occurred in never entered into the equation—its in fact, demonstrable. The businesses in the adjacent building to the Ghost Ship venue were immediately closed in the aftermath of the fire, and within a week were yellow-tagged—basically shut down for business. Nearly two months later, the businesses remain closed, probably permanently.

Yellow Tags on businesses in building adjacent to Ghost Ship mean that the site can’t do business indefinitely.

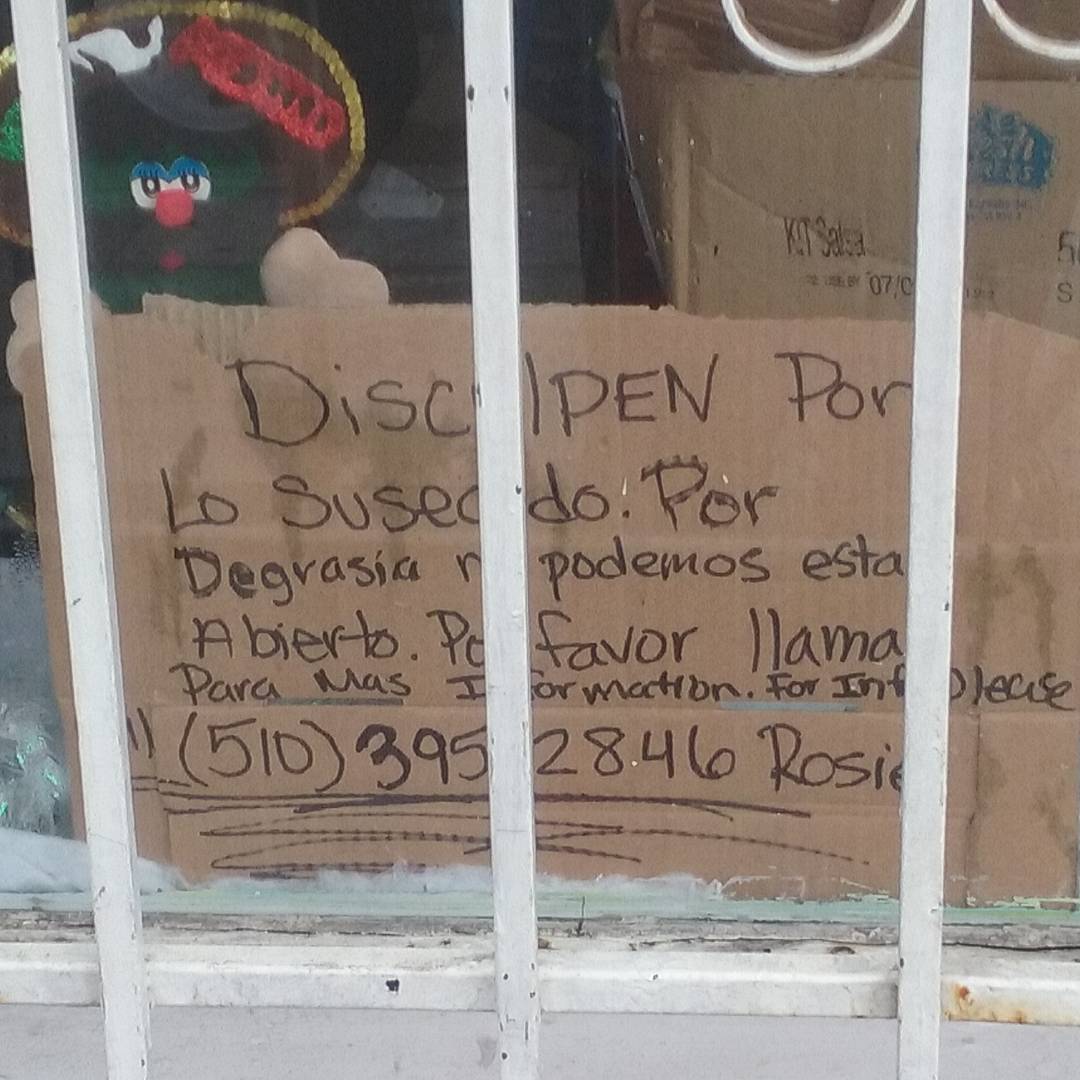

Sign on a business around the corner from Ghostship that was damaged in the fire: “Pardon us for the events, Unfortunately we are not able to open. Please call for more information:”

One owner who I spoke to, who wanted to remain anonymous, told me that no one had ever approached her about fundraising for their shuttered businesses, and that they had, to date, received no funds from any source. As I looked at the collapsing, water-damaged ceiling and the water-damaged furniture and display cases, they told me the city had offered them a loan, which they couldn’t accept given the damage to their livelihood.

It’s not surprising that this mythology about a phantom community in the city’s sights consequently generated a political movement. The Oakland Warehouse Coalition was created by a consortium of live-work residents in the weeks that followed the fire. It garnered an extraordinary amount of influence and attention immediately from City Council officials and the mayor herself that can be said to be nothing short of astonishing, given this demographic’s self-proclaimed status as hunted and marginalized. Within three weeks, the group had convinced city council member Rebecca Kaplan to give them an official audience in the city council chambers. Though Kaplan invited other affordable housing advocates—including more than one that suggested the city rehabilitate distressed housing for the homeless and precariously housed—OWC dominated the proceedings and had the only policy proposal that was given serious attention.

Kaplan also managed to revive a piece of red-tag remedy legislation that had sat idle in the community and economic development committee for over a year, specifically for, and apparently in conjunction with, the OWC. The legislation had to be put on hold again because a shooting on 14th and Broadway disrupted the committee meeting on Tuesday, January 10th. But later that same day, Mayor Schaaf issued an executive order meant to assure her constituency that she was taking them seriously. Despite it being mostly performative, its nevertheless an extraordinary action by a Mayor to ameliorate such a small and relatively new group. The next day at the Rules Committee, members of the OWC seemed to be working as partners with Rebecca Kaplan’s aide to consolidate items on the docket for future consideration by the city council—their own proposed legislation as well as a discussion of the executive order. They were treated as stakeholders, literally as a department of their own, with the director of the OWC addressing the committee without a speakers card.

None of this is to suggest that some or all of the OWC’s policy proposal—which they intend as of this moment to get on a city council agenda as a legislative proposal—are harmful in and of themselves. The modifications to the city’s policy on red tagging residences [4] may be beneficial to people living in substandard and off the books dwellings in some way that remains unclear, for example. The problem is the way the issue of housing has been framed and by who; and the unprecedented amount of deference they immediately received in the aftermath of the Ghost Ship fire.

The deference paid to this group, masks the role in displacement and gentrification that arts, live-work and warehouse spaces have played in Oakland and other historically Black and POC cities for decades. Warehouse spaces may from time to time become victims of displacement, but this is generally after their presence has created a marketable climate and reputation for the neighborhood in the first place—that is, after their own presence and oblivious activities have displaced historic and low-income residents who lived in the community because they literally had no other place to go. This dynamic is age-old, and the plight of warehouse spaces falling victims to their own success is a familiar complaint.

At Kaplan’s informal meeting that I mentioned above, a speaker who took the podium gained prominence as a member of the Saltlick warehouse, stated that his former landlord at a low income Oakland neighborhood was excited a group of white hipsters who planned to do art and throw parties were moving into the place. It increased the value of the neighborhood quickly, and as the speaker lamented, they were summarily evicted from their home to bring in higher rollers seeking an up and coming neighborhood. The story is illustrative of the dynamic of Oakland’s last decade and a half–during the same period that Oakland became famous for its warehouse and venue scene, Oakland’s Black population decreased by 33,000.

This role as front-line gentrification devices is the reason a venue like the Ghost Ship operated openly and illegally for years, while other storefronts dedicated to similarly low-level misdemeanor offenses were shut down at police gun-point around it after scant months of operation. Schaaf’s own arts proclivities unknowable, its clear that her fire-snorting snail car inaugural tour was meant for a very narrow audience—hungry developers looking for new markets to turn around and exploit and the high-rent demographics that would follow them. As exploitable mechanisms of neighborhood development, warehouses have been all-but immune to legal scrutiny by the City of Oakland. Meanwhile, as reminders that such neighborhoods can feel dangerous and threatening to outsiders when their current inhabitants are in control of the public sphere, local speakeasies where equally harmless activities take place are quashed with extreme prejudice.

At best, live-work warehouses in Oakland are estimated by some to number no more than 50. They are not representative of the housing issues that afflict Oakland’s poor and poorly housed. But the reality that many of Oakland’s poor live in other kinds of unregulated, off the books dwellings that are not up to code, safe or normatively covered by Oakland’s tenant protections—especially in East Oakland—has been obscured by the inordinate focus on warehouses and live-work spaces. Even normative rent control legislation can’t help people living in these place. They lack the credit and background to get their names on the leases of a real apartment, or can’t afford anything better in the unaffordable current environment. Even being able to shift from one dangerous unpermitted unit to another, with, for example, Kaplan’s increased red-tag relocation figure, is not a guarantee—Oakland’s poor and poorly housed hold on to bad living situations of their own accord because there are no options available even with the funds to do so.

The frenetic pace of Kaplan and Schaaf’s work to appease the live-work community, with legislation being written and pushed and executive order being issued within a month, is in striking contrast to the city’s reaction to recent publicity around the fact that nearly 10 percent of Fruitvale’s children are suffering from lead poisoning. On the very day that future live-work legislation was gift-wrapped by the Rules committee for a future city council meeting, dueling performative legislation around lead was back-burnered and exiled to committee weeks into the future.

The lead issue from contaminated buildings in Oakland’s West and East has been well-known for years. It entered into the national spotlight because it echoed the poisoning of Flint, Michigan’s water, which drew international attention. Thus, for a short day’s cycle of reporting, they were deemed newsworthy. But the reality is that the city has always known about Frutivale’s lead-painted structures, the lead paint on the carpet’s and floors of poor people’s homes, the lead paint that has saturated the dirt in which Oakland’s poor children play.

And maybe the saddest, or perhaps, realest, takeaway of the twisted post-Ghost Ship narrative is that white people who live in warehouses are worthy of a mayoral executive order, but poor Brown and Black children being poisoned by lead are not.

Correction: The speaker I referred to above was prominent in recorded back and forth’s with E&J barbecue and the Saltlick warehouse during E&J’s press conference, but is not affiliated with Saltlick.

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.