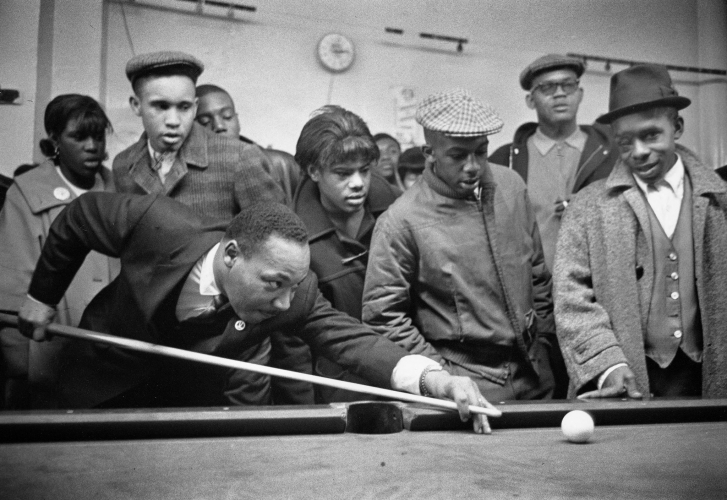

[ Dr. King playing pool in Chicago in 1966.

Bob Fitch, via Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries ]

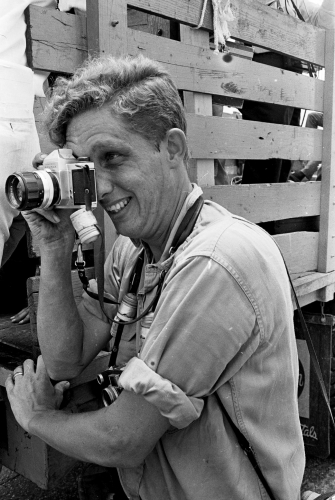

Photo Gallery: Bob Fitch, Photographer of the Civil Rights Era

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2016/05/04/obituaries/bob-fitch-photographer-of-the-civil-rights-era/s/20160504fitch-obit-slide-L4GV.html Bob Fitch, Photojournalist of Civil Rights Era, Dies at 76

Bob Fitch, a self-taught photojournalist whose images chronicled America’s deep-seated ambivalence over civil rights and illustrated the passion underscoring other protest movements since the 1960s, died on Friday at his home in Watsonville, Calif. He was 76.

The cause was complications of Parkinson’s disease, said Brian Murtha, his friend and executor.

“Photojournalism seduced me,” Mr. Fitch wrote on his website. “It was my way to support the organizing for social justice that was transforming history, our lives and future.”

Mr. Fitch, a preacher’s son who became an ordained minister himself, was transformed from a Berkeley, Calif., teenager who rejected religious ritual into an instrument of social justice by sundry catalysts: his family’s fundamental Christian ethos, the writing of James Baldwin and the music of Pete Seeger.

He photographed the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other prominent black civil rights figures as the official chronicler of the organization they founded, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; Dorothy Day of the Catholic Workers Movement; Cesar Chavez of the United Farm Workers (his photo was the prototype for a 2002 postage stamp), and the Jesuit priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan and their followers who opposed the draft and the war in Vietnam. (Daniel Berrigan died on Saturday.)

Ron Dellums, the former California congressman and Oakland mayor, once baptized Mr. Fitch “Bullet Bob,” saying that each vivid shot from his camera was “a bullet of truth into the heart of evil.”

Summoned to Atlanta by Dr. King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, in 1968 to cover her husband’s funeral, Mr. Fitch debated whether to photograph the open coffin.

“It was a tough decision to take that photo,” he told a campus magazine at his alma mater, Lewis & Clark College, in Portland, Ore., last September. “It felt like blasphemy to put a camera in his face. But then I thought, ‘The world needs to see this horrible truth.’”

Clayborne Carson, a Stanford University historian enlisted by Mrs. King to edit her husband’s papers, recalled that Mr. Fitch was so trusted even in unguarded moments that he was the only white person present at an emotional meeting among Dr. King, Stokely Carmichael and other civil rights figures in Greenwood, Miss., in 1966, the night before Mr. Carmichael recast the movement by invoking the slogan “black power.”

Mr. Fitch harbored no illusions, though, about why his offer to sign on as a photographer for the civil rights group had been accepted by Dr. King’s lieutenant, Hosea Williams.

“I was told, ‘Bob, we can’t send African-American journalists and photographers into the field ’cause they’ll get beat up and killed,’” Mr. Fitch recalled in an interview on the website wagingnonviolence.org. “‘Every week you’ll come back with a news story in print and photos, and you’ll send them to the major black print media around the nation.’”

While many photojournalists were assigned to protests primarily in case violence erupted, Mr. Fitch photographed the quotidian consequences of poverty and racially motivated crime and of individual victories, like that of a black man in Batesville, Miss., who, born before the Civil War began, registered to vote for the first time at 106.

Robert De Witt Fitch was born in Los Angeles on July 20, 1939. His father, Robert, was a United Church of Christ minister and professor of Christian ethics. His mother was the former Marion Weeks De Witt.

After attending high school in Berkeley in the 1950s, where he mingled with a socially conscious crowd, he graduated from Lewis & Clark in 1961 with a bachelor’s degree in psychology and later earned a bachelor’s and a master’s of divinity at the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, where his father was dean. He was ordained by the United Church of Christ in 1965.

During an internship at Glide Memorial United Methodist Church in San Francisco, he worked with street gangs, the homeless, hippies and gay, lesbian and transsexual groups and was later a labor organizer and draft resistance counselor. He also worked for the California Department of Housing and the Resource Center for Nonviolence in Santa Cruz, about 15 miles northwest of Watsonville, where he had lived since 2008.

Mr. Fitch took up photography after Glide Memorial asked him to provide pictures for books on urban issues that the church had begun publishing. He consulted professionals, took free courses, studied the works of Dorothea Lange and Henri Cartier-Bresson and discovered, he said, that “I had a pretty good eye.” He volunteered his services to an acquaintance at the Southern Christian Leadership Council and was invited to visit.

In 2014, encouraged by Dr. Carson, the founding director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford, Mr. Fitch transferred his collection of about 275,000 images and negatives to the university with the proviso that they be available to researchers.

His photographs have been featured in Smithsonian Institution exhibits and in books, including “This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement” published in 2011.

Mr. Fitch is survived by his partner, Karen Denise Schaffer; a daughter, Nicole Ma Ka Wa Alexander; two sons, Daniel Robert Jaxon Ravens, the chairman of the Democratic Party in Washington State, and Benjamin Andrew Fitch, an actor; two grandchildren; and a sister, Shelley Herting.

His friend Mr. Murtha said he died at home as he paused while reading Dr. King’s prescriptive book “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?,” which was published less than a year before he was assassinated in 1968. Mr. Fitch once said that he had been inspired to join Dr. King after reading “The Fire Next Time,” James Baldwin’s seminal 1963 book expressing anger and despair over the state of race relations.

“I had a vision of myself being engaged with what I had encountered in the book in some sort of aesthetic manner,” Mr. Fitch recalled. “I decided the next morning that the ‘aesthetic’ would not be writing — writing’s too hard — and it wouldn’t be as a painterly artist,” he said, “but maybe photography, since I had developed those skills as a hobby.”

He expanded on his life’s work in talking to a group of college students a few years ago. “I’m not a professional photographer, I’m a political organizer,” he said. “I happen to use the camera to tell the story of the work I do.”

---------

A version of this article appears in print on May 4, 2016, on page A18 of the New York edition with the headline: Bob Fitch, 76, Activist Photographer Who Captured Civil Rights Era, Dies.