From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Are Charter School Directors Bending Pension Rules? A Pension Rip-off By Charter Operator

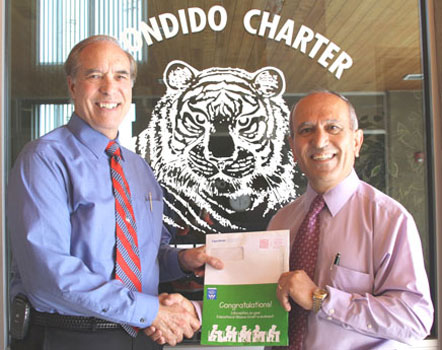

A charter school operator Dennis Snyder in Escondido manipulating the California State Retirement System (CalSTRS) is getting $118,700 pension plus a salary of $104,500 from a publicly funded privately run charter school run by the American Education Foundation. The systemic corruption and rip-off of public funds by the charter school industry is exploding.

Are Charter School Directors Bending Pension Rules? Snyder’s yearly pension has now grown to $118,700. In addition, he receives a salary of $104,500 as the executive director of the American Heritage Education Foundation. Some critics say that his duties did not change when he “retired,” and that by taking this salary he is “double dipping” in the system.

http://www.escondidoalliance.com/author/mercurio/are-charter-school-directors-bending-pension-rules/

Posted on October 2, 2015 by admin

By Rick Mercurio

Teachers and administrators in California’s public schools earn pensions based on several factors. For some, like Dennis Snyder, the founder of three charter schools in Escondido CA, it adds up to a healthy lifetime benefit, even though his final employer was not a public school district, and even though he found an apparent loophole in the regulations.

Snyder’s situation

Dennis Snyder worked as a teacher and football coach at Escondido High School starting in about 1965. In 1986 the principal fired Snyder as coach, citing the reason that he was not cooperative with the parent booster organization. Snyder appealed the firing to both the superintendent and the school board, and he lost both appeals.

Although he was let go as head football coach, he retained his teaching position. However, in the early ‘90s Snyder switched jobs, becoming executive director of the Escondido Charter High School, which he founded. Heritage K-8 Charter School and Heritage Digital Academy were later founded by Snyder as well.

Snyder’s salary as executive director eventually rose to almost $111,000. In 2007 he officially “retired” from that job, and began receiving his teacher pension through the California State Retirement System (CalSTRS). The formula counted his years as a teacher in the public Escondido Union High School District added to his years at the charter school. His compensation as director was determined privately by internal charter school decision makers; it was not tied to any public school salary schedule.

Scott Thompson was a pension program analyst in the Service Retirement Division at CalSTRS from April 2005 through January 2011. His job was to ensure retiree benefits were correctly calculated in accordance with state law.

Thompson sees a pattern at charter schools. “This is one of the fundamental flaws of the charter system,” he stated. “Board members are typically hand picked by the founder, largely for their allegiance to him/her. It should therefore come as no surprise that the board considers the founder worthy of compensation far in excess of what their counterparts receive at schools with similar student populations.”

So Snyder had 42 years of service, at age 65, with a final compensation of about $111,000, with the $400 per month longevity bonus. The formula resulted in his initial pension of about $104,000, much higher than the average retiring educator. (See details below about how pensions are calculated.)

Michael Sicilia, CalSTRS Media Relations Manager, explained that charter schools may choose whether charter school employees including administrators are participants.

“On Element 11 of Snyder’s Escondido Charter High School charter petition, the charter school identifies the retirement benefits for all employees,” Sicilia stated. If CalSTRS was identified as the retirement benefit for the certificated employees, including administrators, then this charter school will have to be in compliance with all the sections of Teacher Retirement Law, from its first day of performing STRS creditable service. Any charter school that elected CalSTRS will be treated by STRS just like a regular public school district.

July 1, 1999, was the effective date for CalSTRS participation at ECHS.”

Public vs. Private

Although taxpayers fund charter schools, some have been known to loudly proclaim that they are not part of the public school system when it suits them. Yet when the monetary advantages of the public system beckon, such as participating in STRS, they change their tune.

In Washington State, this question of private vs. public was recently answered.

The Seattle Times reported on a landmark ruling on Sept. 4. “After nearly a year of deliberation, the state Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that charter schools are unconstitutional…The ruling — believed to be one of the first of its kind in the country — overturns the law voters narrowly approved in 2012 allowing publicly funded, but privately operated, schools.”

Diane Ravitch, an education historian, an educational policy analyst, and a research professor at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, wrote in an October 2013 blog, “Charter Schools Insist: We are Private, not Public.”

Ravitch reported that the California Charter Schools Association (CCSA) said that “charter schools are not subject to the laws governing public schools. CCSA says that charter schools are exempt from criminal laws governing public schools because they are operated by a private corporation. They say the money received for their nonprofit corporation is not public money, even though it comes from the state and from taxpayers.”

Ravitch continues: “CCSA maintains … that the Legislature has expressly allowed charter schools to be operated by private nonprofit corporations, …(and) the court cases and administrative agency decisions make clear that these private officers and employees of the nonprofit corporation are not subject to (state penal laws) because these nonprofit corporations are private entities, with private employees, expending private moneys (i.e., not “public moneys”).”

Ravitch opines “that we should accept the claims of the California Charter Schools Association that charter schools are private entities, managed by private corporations that are outside the purview of the law. Is this really a good development for American public education? One set of schools (charter schools) receiving public funds but exempt from the law, and another set of schools (public schools) closely regulated by the state? One set of schools (charter schools) free to set their own discipline policy, free to enroll few students with disabilities and English learners, while another set of schools (public schools) must accept everyone, including the students excluded or tossed out of the charter schools.

Does it make sense to give public money to schools that are neither transparent nor accountable for their use of that money and unwilling to comply with state laws?”

Gaming the System?

Snyder’s yearly pension has now grown to $118,700. In addition, he receives a salary of $104,500 as the executive director of the American Heritage Education Foundation. Some critics say that his duties did not change when he “retired,” and that by taking this salary he is “double dipping” in the system. CalSTRS places an annual cap of $40,173 on retired teachers going back to work as educators.

Thompson has seen this before. “ Yes, he’s doing the same job, but moving the money around in order to circumvent the rules,” he stated. “It should come as no surprise to anyone that people who found charter schools do not like to follow the rules that apply to everyone else. Indeed, that is no doubt one of the main reasons they found charter schools.”

According to the Times of San Diego, CalSTRS investigated Snyder’s case and cleared him of any technical wrongdoing. The reason cited is that his current “employer” is now a private foundation, even though his duties are apparently identical to when he was under CalSTRS as a charter school employee.

Thompson was not surprised. “This is not unusual,” he stated. “Although state law is written to protect public funds from those who would game the system, they are still public funds, which means CalSTRS administrators are playing with house money, not their own. They are therefore inclined to err on the side of leniency when someone tries to bend the rules. They are less averse to the risk of disbursing public funds to someone not entitled to them, than to the risk of provoking a lawsuit from a member who has the nerve to cheat and then double-down on their malfeasance with legal action.”

Alianza publisher Nina Deerfield and reporter Rebecca Nutile issued a statement, saying they were troubled by the recent ruling clearing Snyder.

“Charter schools and their operators thrive in these types of loopholes and it is concerning this one is being allowed,” Deerfield and Nutile said.

“Perhaps CalSTRS needs to look into closing this particular loophole as it has opened the door for other operators to do the same — collect a full pension and simply move the salary source from the school to a related organization instead of actually leaving their position or working for the school at a salary below the supposed CalSTRS cap [of $40,173].”

Other administrators in the San Diego County public pension system have been penalized in similar situations, they said. “The primary difference seems to be that they were involved in the real public schools, not the nebulous world of privatized charter schools,” Deerfield and Nutile said. “When public school employees retire from the school system, they are required to actually retire and make room for someone else — or work in the school below the CalSTRS salary cap.”

Thompson agrees. “Yes, (Snyder’s) clearly gaming the system,” he stated. “Those who are inclined to do so think anyone who chooses not to is not ethical, but rather a fool. There’s no risk in trying when the worst that can happen is that the bid will be denied. This rarely happens. When the penalty for cheating is nothing more than a slap on the wrist, and even that is unlikely if the gamer is savvy, as most charter school founders are when it comes to rules, then the incentive to try is strong.”

How Teacher Pensions Work

CalSTRS offers defined benefits to participants. This means that the amount paid to retirees each month is a set formula, not related to how much that individual contributed to the system over their career. Defined benefit programs were created after hard-fought negotiations by teacher unions, who attempted to ensure adequate retirement for college-educated teachers who gave long years of service for relatively low pay. Unlike defined benefit systems whereby a public employee can count on a certain amount given their years of service and age, a 401(K) plan involves risk about what amount of money would be available upon retirement.

Defined benefits have come under attack from the political right. More and more employers, both public and private, are opting for the alternative: defined contribution. This is typically a 401(k) retirement account, whereby employees will eventually receive a pension based solely on monetary contributions over the employee’s time of service. Some employers may match the monthly payments by the employee.

Teachers in California pay just over 8% of their salary to CalSTRS, and the school districts contribute a little more. The unfunded liability of CalSTRS grew to over $70 billion, alarming state officials. In response, Governor Jerry Brown initiated new legislation, which increases both of these percentages over time, with the district’s share rising to 19% in a few years. This, officials believe, should bring the system into financial solvency.

Calculating Pensions

The formula for CalSTRS pensions involves multiplying three numbers: an age factor, years of teaching service, and final compensation. The age factor is a multiplier with 2% pegged to 60 years. If you retire before 60, the factor decreases incrementally for each month. For those who retire after age 60, the factor increases up to a maximum of 2.4%. For those with more than 30 years service, add 0.2% to the age factor.

Years of service increase slightly by adding any unused sick leave. As for final compensation, with 25 or more years of service only the highest year of compensation is used. For retirees who have fewer than 25 years, an average of the three highest years is used to determine final compensation.

In addition, CalSTRS sweetened the pot for teachers who had 30 or more years of service by December of 2010. For 30 years, add $200 per month; for 31 years, add $300 per month; for 32 or more years, add $400 per month. In addition, CalSTRS increases the pension by 2% every year, although this is not compounded.

As one example, let’s say Teacher A retires at age 60 after 25 years of service (including unused sick leave). Her highest yearly compensation was $64,000. Multiply the age factor (2%) by the years of service (25) times the compensation ($64K). Her pension would start at $32,000 per year for the rest of her life. If she chose a plan whereby a beneficiary would receive all or a portion of her pension upon her death, then the monthly amount would decrease proportionally.

If Teacher B retired at age 65 after 35 years of service with a final compensation of $76,000, her annual pension would be determined as follows: 2.4% age factor times 35 times 76K plus $400 per month bonus. Her yearly pension would begin at $68,640.

Teachers A and B illustrate typical pensions for long-term teachers and they are substantially lower than Mr. Snyder’s. If teachers A&B were to go back to work in the public school system, they could not earn more than the CalSTRS salary cap if they wish to collect their full pension. However, it appears they could work at a charter school and simply have their salaries paid from a private pot of money and be completely exempt from CalSTRS post-retirement regulations. Again, charter schools and their operators claim to be public when it suits their needs and private when it suits their needs. It appears charter schools are even allowed to designate some employees part of the public CalSTRS system and others part of a private system depending on whether the employees wish to build their pensions or collect them.

http://www.escondidoalliance.com/author/mercurio/are-charter-school-directors-bending-pension-rules/

Posted on October 2, 2015 by admin

By Rick Mercurio

Teachers and administrators in California’s public schools earn pensions based on several factors. For some, like Dennis Snyder, the founder of three charter schools in Escondido CA, it adds up to a healthy lifetime benefit, even though his final employer was not a public school district, and even though he found an apparent loophole in the regulations.

Snyder’s situation

Dennis Snyder worked as a teacher and football coach at Escondido High School starting in about 1965. In 1986 the principal fired Snyder as coach, citing the reason that he was not cooperative with the parent booster organization. Snyder appealed the firing to both the superintendent and the school board, and he lost both appeals.

Although he was let go as head football coach, he retained his teaching position. However, in the early ‘90s Snyder switched jobs, becoming executive director of the Escondido Charter High School, which he founded. Heritage K-8 Charter School and Heritage Digital Academy were later founded by Snyder as well.

Snyder’s salary as executive director eventually rose to almost $111,000. In 2007 he officially “retired” from that job, and began receiving his teacher pension through the California State Retirement System (CalSTRS). The formula counted his years as a teacher in the public Escondido Union High School District added to his years at the charter school. His compensation as director was determined privately by internal charter school decision makers; it was not tied to any public school salary schedule.

Scott Thompson was a pension program analyst in the Service Retirement Division at CalSTRS from April 2005 through January 2011. His job was to ensure retiree benefits were correctly calculated in accordance with state law.

Thompson sees a pattern at charter schools. “This is one of the fundamental flaws of the charter system,” he stated. “Board members are typically hand picked by the founder, largely for their allegiance to him/her. It should therefore come as no surprise that the board considers the founder worthy of compensation far in excess of what their counterparts receive at schools with similar student populations.”

So Snyder had 42 years of service, at age 65, with a final compensation of about $111,000, with the $400 per month longevity bonus. The formula resulted in his initial pension of about $104,000, much higher than the average retiring educator. (See details below about how pensions are calculated.)

Michael Sicilia, CalSTRS Media Relations Manager, explained that charter schools may choose whether charter school employees including administrators are participants.

“On Element 11 of Snyder’s Escondido Charter High School charter petition, the charter school identifies the retirement benefits for all employees,” Sicilia stated. If CalSTRS was identified as the retirement benefit for the certificated employees, including administrators, then this charter school will have to be in compliance with all the sections of Teacher Retirement Law, from its first day of performing STRS creditable service. Any charter school that elected CalSTRS will be treated by STRS just like a regular public school district.

July 1, 1999, was the effective date for CalSTRS participation at ECHS.”

Public vs. Private

Although taxpayers fund charter schools, some have been known to loudly proclaim that they are not part of the public school system when it suits them. Yet when the monetary advantages of the public system beckon, such as participating in STRS, they change their tune.

In Washington State, this question of private vs. public was recently answered.

The Seattle Times reported on a landmark ruling on Sept. 4. “After nearly a year of deliberation, the state Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that charter schools are unconstitutional…The ruling — believed to be one of the first of its kind in the country — overturns the law voters narrowly approved in 2012 allowing publicly funded, but privately operated, schools.”

Diane Ravitch, an education historian, an educational policy analyst, and a research professor at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, wrote in an October 2013 blog, “Charter Schools Insist: We are Private, not Public.”

Ravitch reported that the California Charter Schools Association (CCSA) said that “charter schools are not subject to the laws governing public schools. CCSA says that charter schools are exempt from criminal laws governing public schools because they are operated by a private corporation. They say the money received for their nonprofit corporation is not public money, even though it comes from the state and from taxpayers.”

Ravitch continues: “CCSA maintains … that the Legislature has expressly allowed charter schools to be operated by private nonprofit corporations, …(and) the court cases and administrative agency decisions make clear that these private officers and employees of the nonprofit corporation are not subject to (state penal laws) because these nonprofit corporations are private entities, with private employees, expending private moneys (i.e., not “public moneys”).”

Ravitch opines “that we should accept the claims of the California Charter Schools Association that charter schools are private entities, managed by private corporations that are outside the purview of the law. Is this really a good development for American public education? One set of schools (charter schools) receiving public funds but exempt from the law, and another set of schools (public schools) closely regulated by the state? One set of schools (charter schools) free to set their own discipline policy, free to enroll few students with disabilities and English learners, while another set of schools (public schools) must accept everyone, including the students excluded or tossed out of the charter schools.

Does it make sense to give public money to schools that are neither transparent nor accountable for their use of that money and unwilling to comply with state laws?”

Gaming the System?

Snyder’s yearly pension has now grown to $118,700. In addition, he receives a salary of $104,500 as the executive director of the American Heritage Education Foundation. Some critics say that his duties did not change when he “retired,” and that by taking this salary he is “double dipping” in the system. CalSTRS places an annual cap of $40,173 on retired teachers going back to work as educators.

Thompson has seen this before. “ Yes, he’s doing the same job, but moving the money around in order to circumvent the rules,” he stated. “It should come as no surprise to anyone that people who found charter schools do not like to follow the rules that apply to everyone else. Indeed, that is no doubt one of the main reasons they found charter schools.”

According to the Times of San Diego, CalSTRS investigated Snyder’s case and cleared him of any technical wrongdoing. The reason cited is that his current “employer” is now a private foundation, even though his duties are apparently identical to when he was under CalSTRS as a charter school employee.

Thompson was not surprised. “This is not unusual,” he stated. “Although state law is written to protect public funds from those who would game the system, they are still public funds, which means CalSTRS administrators are playing with house money, not their own. They are therefore inclined to err on the side of leniency when someone tries to bend the rules. They are less averse to the risk of disbursing public funds to someone not entitled to them, than to the risk of provoking a lawsuit from a member who has the nerve to cheat and then double-down on their malfeasance with legal action.”

Alianza publisher Nina Deerfield and reporter Rebecca Nutile issued a statement, saying they were troubled by the recent ruling clearing Snyder.

“Charter schools and their operators thrive in these types of loopholes and it is concerning this one is being allowed,” Deerfield and Nutile said.

“Perhaps CalSTRS needs to look into closing this particular loophole as it has opened the door for other operators to do the same — collect a full pension and simply move the salary source from the school to a related organization instead of actually leaving their position or working for the school at a salary below the supposed CalSTRS cap [of $40,173].”

Other administrators in the San Diego County public pension system have been penalized in similar situations, they said. “The primary difference seems to be that they were involved in the real public schools, not the nebulous world of privatized charter schools,” Deerfield and Nutile said. “When public school employees retire from the school system, they are required to actually retire and make room for someone else — or work in the school below the CalSTRS salary cap.”

Thompson agrees. “Yes, (Snyder’s) clearly gaming the system,” he stated. “Those who are inclined to do so think anyone who chooses not to is not ethical, but rather a fool. There’s no risk in trying when the worst that can happen is that the bid will be denied. This rarely happens. When the penalty for cheating is nothing more than a slap on the wrist, and even that is unlikely if the gamer is savvy, as most charter school founders are when it comes to rules, then the incentive to try is strong.”

How Teacher Pensions Work

CalSTRS offers defined benefits to participants. This means that the amount paid to retirees each month is a set formula, not related to how much that individual contributed to the system over their career. Defined benefit programs were created after hard-fought negotiations by teacher unions, who attempted to ensure adequate retirement for college-educated teachers who gave long years of service for relatively low pay. Unlike defined benefit systems whereby a public employee can count on a certain amount given their years of service and age, a 401(K) plan involves risk about what amount of money would be available upon retirement.

Defined benefits have come under attack from the political right. More and more employers, both public and private, are opting for the alternative: defined contribution. This is typically a 401(k) retirement account, whereby employees will eventually receive a pension based solely on monetary contributions over the employee’s time of service. Some employers may match the monthly payments by the employee.

Teachers in California pay just over 8% of their salary to CalSTRS, and the school districts contribute a little more. The unfunded liability of CalSTRS grew to over $70 billion, alarming state officials. In response, Governor Jerry Brown initiated new legislation, which increases both of these percentages over time, with the district’s share rising to 19% in a few years. This, officials believe, should bring the system into financial solvency.

Calculating Pensions

The formula for CalSTRS pensions involves multiplying three numbers: an age factor, years of teaching service, and final compensation. The age factor is a multiplier with 2% pegged to 60 years. If you retire before 60, the factor decreases incrementally for each month. For those who retire after age 60, the factor increases up to a maximum of 2.4%. For those with more than 30 years service, add 0.2% to the age factor.

Years of service increase slightly by adding any unused sick leave. As for final compensation, with 25 or more years of service only the highest year of compensation is used. For retirees who have fewer than 25 years, an average of the three highest years is used to determine final compensation.

In addition, CalSTRS sweetened the pot for teachers who had 30 or more years of service by December of 2010. For 30 years, add $200 per month; for 31 years, add $300 per month; for 32 or more years, add $400 per month. In addition, CalSTRS increases the pension by 2% every year, although this is not compounded.

As one example, let’s say Teacher A retires at age 60 after 25 years of service (including unused sick leave). Her highest yearly compensation was $64,000. Multiply the age factor (2%) by the years of service (25) times the compensation ($64K). Her pension would start at $32,000 per year for the rest of her life. If she chose a plan whereby a beneficiary would receive all or a portion of her pension upon her death, then the monthly amount would decrease proportionally.

If Teacher B retired at age 65 after 35 years of service with a final compensation of $76,000, her annual pension would be determined as follows: 2.4% age factor times 35 times 76K plus $400 per month bonus. Her yearly pension would begin at $68,640.

Teachers A and B illustrate typical pensions for long-term teachers and they are substantially lower than Mr. Snyder’s. If teachers A&B were to go back to work in the public school system, they could not earn more than the CalSTRS salary cap if they wish to collect their full pension. However, it appears they could work at a charter school and simply have their salaries paid from a private pot of money and be completely exempt from CalSTRS post-retirement regulations. Again, charter schools and their operators claim to be public when it suits their needs and private when it suits their needs. It appears charter schools are even allowed to designate some employees part of the public CalSTRS system and others part of a private system depending on whether the employees wish to build their pensions or collect them.

For more information:

http://www.escondidoalliance.com/author/me...

Add Your Comments

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network