From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Santa Cruz Indymedia

U.S.

Government & Elections

Health, Housing & Public Services

Police State & Prisons

Community Alert: PredPol Company and Involvement of Local Politicians

Several local politician/community figure types have been involved in the formation, marketing, and ongoing operation of a local startup company called "PredPol". This company claims to make crime-predicting software which they want police departments across the country to buy. There are some who think they are just blatant prison-industrial complex profiteers abusing their political connections to become rich on the backs of the 99%.

The real scoop on this has been censored in the local media. After reading the links below, including the SF Weekly investigative article, you'll understand why.

The real scoop on this has been censored in the local media. After reading the links below, including the SF Weekly investigative article, you'll understand why.

Community Alert: PredPol Company and Involvement of Local Politicians

by Ladies_and_Gentlemen

Monday Mar 16th, 2015

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Please be advised of the questionable involvement of several local politician/community figure types in the formation, marketing, and ongoing operation of a local startup company called "PredPol". This company claims to make crime-predicting software which they want police departments across the country to buy. There are some who think they are blatant prison-industrial complex profiteers abusing their Democratic-party connections. The SF Weekly article (link below) does a great job of exposing the ethical problems related to the way this startup has been "operating" (censored in local Monterey Bay media). Basically, they have claimed as "customers" many police departments who have not paid for the software and are using it strictly on a trial basis. Predpol has also been pressuring these same departments to give false "testimonials" for their software. Some Police Dept heads, including in SF, have objected to this political-sweatshop behavior.

Up until recently, there was even a CIA (InQTel) employee on the Board of Directors (they figured out this would be PR-negative).

The local figures hoping to become rich from this are: Ryan Coonerty, Caleb Baskin, Zach Friend, and Donnie Fowler (apologies if I missed anybody). They have been coordinating their actions in order to keep this information from, and deceive, the public.

The real scoop on this has been censored in the local media. After reading the links below, including the SF Weekly investigative article, you'll understand why.

Let's not allow this kind of prison-industrial complex profiteering to happen in our community !!! Hypocrites, false progressives, and prison-industrial profiteers clearly must be stopped in their tracks.

SF Weekly Article:

http://www.sfweekly.com/sanfrancisco/all-tomorrows-crimes-the-future-of-policing-looks-a-lot-like-good-branding/Content?oid=2827968

Techdirt Magazine:

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20131031/13033125091/predictive-policing-company-uses-bad-stats-contractually-obligated-shills-to-tout-unproven-successes.shtml

Safe Growth Blog:

http://safe-growth.blogspot.fr/2013/11/a-bad-week-for-predictive-policing.html

PEACE OUT

by Ladies_and_Gentlemen

Monday Mar 16th, 2015

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Please be advised of the questionable involvement of several local politician/community figure types in the formation, marketing, and ongoing operation of a local startup company called "PredPol". This company claims to make crime-predicting software which they want police departments across the country to buy. There are some who think they are blatant prison-industrial complex profiteers abusing their Democratic-party connections. The SF Weekly article (link below) does a great job of exposing the ethical problems related to the way this startup has been "operating" (censored in local Monterey Bay media). Basically, they have claimed as "customers" many police departments who have not paid for the software and are using it strictly on a trial basis. Predpol has also been pressuring these same departments to give false "testimonials" for their software. Some Police Dept heads, including in SF, have objected to this political-sweatshop behavior.

Up until recently, there was even a CIA (InQTel) employee on the Board of Directors (they figured out this would be PR-negative).

The local figures hoping to become rich from this are: Ryan Coonerty, Caleb Baskin, Zach Friend, and Donnie Fowler (apologies if I missed anybody). They have been coordinating their actions in order to keep this information from, and deceive, the public.

The real scoop on this has been censored in the local media. After reading the links below, including the SF Weekly investigative article, you'll understand why.

Let's not allow this kind of prison-industrial complex profiteering to happen in our community !!! Hypocrites, false progressives, and prison-industrial profiteers clearly must be stopped in their tracks.

SF Weekly Article:

http://www.sfweekly.com/sanfrancisco/all-tomorrows-crimes-the-future-of-policing-looks-a-lot-like-good-branding/Content?oid=2827968

Techdirt Magazine:

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20131031/13033125091/predictive-policing-company-uses-bad-stats-contractually-obligated-shills-to-tout-unproven-successes.shtml

Safe Growth Blog:

http://safe-growth.blogspot.fr/2013/11/a-bad-week-for-predictive-policing.html

PEACE OUT

For more information:

http://www.predpol.com

Add Your Comments

Comments

(Hide Comments)

It's been going on for decades, and UCSC is a player, as is DLI, and the Highlands Forum (as in Carmel Highlands).

"Known as the ‘Highlands Forum,’ this private network has operated as a bridge between the Pentagon and powerful American elites outside the military since the mid-1990s."

https://medium.com/@NafeezAhmed/how-the-cia-made-google-e836451a959e

See also: Secret History Of Silicon Valley.

http://steveblank.com/secret-history/

I assume the PredPol deals include local data from those test PDs...

"Known as the ‘Highlands Forum,’ this private network has operated as a bridge between the Pentagon and powerful American elites outside the military since the mid-1990s."

https://medium.com/@NafeezAhmed/how-the-cia-made-google-e836451a959e

See also: Secret History Of Silicon Valley.

http://steveblank.com/secret-history/

I assume the PredPol deals include local data from those test PDs...

For more information:

http://PeaceCamp2010insider.blogspot.com/

SCPD Deputy Chief Steve Clark.

And then there's this . . . .

http://www.santacruzsentinel.com/general-news/20100929/santa-cruz-city-council-oks-changes-to-historic-cottage-owned-by-vice-mayors-business-partner

They seem to take advantage of other people and abuse their positions in local government far too often, worse than some republicans ! It's a miracle the above Sentinel story was even published, given the apparent (current) stranglehold the Coonertys have on local media.

I'm surprised that the people of Santa Cruz would give such blind support to these people. But I suppose the editors of Good Times, Sentinel, etc are beholden to them as part of the local political tribute food chain.

I say kick them out, and elect people like Leonie Sherman instead (disclosure: never met her, but like her articles in Adventure Sports Mag).

Good Luck to All.

http://www.santacruzsentinel.com/general-news/20100929/santa-cruz-city-council-oks-changes-to-historic-cottage-owned-by-vice-mayors-business-partner

They seem to take advantage of other people and abuse their positions in local government far too often, worse than some republicans ! It's a miracle the above Sentinel story was even published, given the apparent (current) stranglehold the Coonertys have on local media.

I'm surprised that the people of Santa Cruz would give such blind support to these people. But I suppose the editors of Good Times, Sentinel, etc are beholden to them as part of the local political tribute food chain.

I say kick them out, and elect people like Leonie Sherman instead (disclosure: never met her, but like her articles in Adventure Sports Mag).

Good Luck to All.

For more information:

http://www.santacruzsentinel.com/general-n...

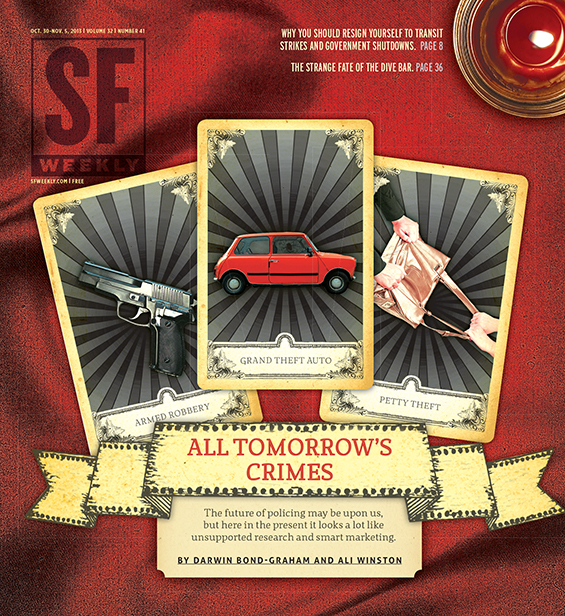

All Tomorrow's Crimes: The Future of Policing Looks a Lot Like Good Branding

By Darwin Bond-Graham and Ali Winston

Wednesday, Oct 30 2013

The day before Halloween in 2012, Donnie Fowler, a lobbyist from a little-known tech start-up called PredPol, e-mailed a confidential login and password to the San Francisco Police Department's chief information officer, Susan Merritt. The password allowed Merritt to log into an online mapping tool that, according to Fowler and his business partners, was already predicting where crimes are likely to happen across San Francisco.

Fowler was, if his company is to be believed, giving the SFPD the keys to the next generation of crime-fighting, a program that draws from the past to help police, presumably, change the future. PredPol was hoping San Francisco would be wooed by the sci-fi promise of its product. After all, the media certainly has been.

Every other news article and TV clip about PredPol to appear over the past year, from Al Jazeera to the Wall Street Journal, has showcased the company and its software as if it were straight out of Philip K. Dick's short story, "The Minority Report." An algorithm, the exact nature of which is a proprietary secret closely guarded by PredPol, processes the inputted data and spits out 500-by-500 square-foot boxes on a map of the city. In these boxes, according to PredPol, the risk of crimes like auto-theft or battery are more likely to occur. Police access the program through a web browser. Its display is similar to Google maps, and features allowing cops to toggle different crimes, and zoom in on particular blocks, are simple and intuitive. For more than a year, the SFPD has quietly handed over troves of crime data to PredPol and allowed the company to integrate this software with the city's new police information technology systems.

Thousands of tech start-ups are popping up in the Bay Area these days, so it should come as little surprise that a few are selling apps to the police. PredPol, short for "predictive policing," is riding this wave of techno-mania and capitalizing on the belief, especially here in San Francisco, that there's a killer app for everything, including crime-fighting. This is a shift for the SFPD, a department that finally issued e-mail addresses to all of its officers and equipped its precincts with Internet connections in 2011.

The SFPD has yet to sign a contract with PredPol, but the company has aggressively marketed its software throughout the United States and overseas, winning hundreds of thousands of dollars in contracts. The company is run by politically connected individuals with ties to local and national Democratic Party leadership. It is backed by powerful Silicon Valley investors, and while the company's executives say the software originates from earthquake research, it actually is derived more from Army research into insurgencies and battlefield casualties.

And it's got a marketing strategy that recalls a military conquest. PredPol has required police departments that sign on to refer the company to other law enforcement agencies, and to appear in flashy press conferences, endorsing the software as a crime-reducer — despite the fact that its effectiveness hasn't yet been proven.

While PredPol is promoting its software and ginning up reams of good press for itself, veteran cops and prominent academics are skeptical about this latest crime-fighting gadget. Some say predictive policing doesn't work. Some even say specifically that PredPol's algorithm doesn't accurately predict future crimes, and that it has no proven record of reducing crime rates. Yet, without a contract, without public notice, even without most members of the Police Commission — the civilian body that oversees SFPD — knowing, the SFPD and PredPol have prepared to launch the company's controversial crime prediction software. As PredPol engineer Omar Qazi told SFPD staff back in February in an e-mail, "we can literally start generating predictions for you tomorrow."

Others worry that gadget-obsessed police and their contractors will not just waste public dollars on snake-oil solutions, but that in the process they'll actually undermine public safety. Kade Crockford, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts' Technology for Liberty Project, warns against the trend towards data and statistical software as a panacea. "People are excited about technological solutions for vexing social problems," Crockford says. "This is technophilia that's taken over. People assume if computers are involved, then it's smarter, more efficient."

PredPol's first inroads into San Francisco came at the initiative of Police Commissioner Suzy Loftus, a former prosecutor and policy specialist with the San Francisco District Attorney and the California Attorney General's Office. On May 17, 2012, Loftus was introduced to PredPol CEO Caleb Baskin and lobbyist Fowler. Loftus says that she first heard of predictive policing while working at the California Department of Justice.

"As a Police Commissioner, one of my primary goals is to support the department in adopting technology as a tool to solve, as well as prevent, crime," Loftus says in an e-mail. "After hearing more about this technology, I thought that SFPD and the Chief [Greg Suhr] should learn about it and decide if they thought it would be a good fit for the department. I called the Chief and told him what I thought about the potential and gave Donnie [Fowler] Greg's e-mail."

The civilian San Francisco Police Commission does not usually get involved with awarding contracts. While Loftus' contact with PredPol is not prohibited by her position as police commissioner, it is outside the scope of her official duties. Neither commission President Thomas Mazzucco nor Commissioner Angela Chan were aware of SFPD's relationship with PredPol, or of Loftus' introduction of the firm to SFPD's higher-ups.

"Good to meet both of you today," Loftus wrote Baskin and Fowler. "I am fascinated by what is possible here. I called [C]hief Suhr about it and told him that I met with you guys and think that if he likes it, it could be great for [San Francisco]."

After listening to Loftus, Suhr put PredPol's Fowler in touch with SFPD's Chief Information Officer, Susan Merritt. Thus began a year and a half of negotiation between the SFPD and PredPol over implementing the crime forecasting technology in the city — first as a no-cost demonstration in the Mission District, and then on a city-wide basis.

From the beginning, the effectiveness of PredPol had been a sticking point in the negotiations.

SFPD's Merritt was skeptical. In a series of e-mails from July 2012 to August 2013, Fowler laid out the technical specifications for the software and the types of crimes PredPol claims to predict. "The crimes we predict are burglary [residential, commercial, auto], auto theft, theft, robbery, assault, battery, and drug crime," Fowler wrote on July 23, 2012. "This goes significantly beyond your current ... mapping tools," he added. Affixed to Fowler's e-mail signature was the claim that PredPol's predictions are "twice as accurate as those made by vet cops."

Fowler's e-mails also make it clear that PredPol viewed the SFPD as a major potential contract that would drum up more business. The price, Fowler wrote on July 23, was "$150,000 with a 50 percent discount for signing up as one of the 15-20 early showcase cities nationally and a commitment for collaboration over the next three years." These showcase cities included Salinas, Seattle, and Alhambra.

Merritt pressed Fowler about whether the program could handle violent crime. "Homicide is a priority in the department — and if it is not there it would just beg the question why not," she wrote. Fowler admitted at the time that PredPol wasn't predicting homicides and gun violence. Failing to rope SFPD into its 15-20 city pilot program last year, PredPol devised a new idea, based on the demand for a tool to predict violent crimes, to include San Francisco in a gun-violence pilot program with Atlanta and Detroit. That would have used the three cities as case studies in its nationwide marketing push. When Detroit backed out, and San Francisco stalled, PredPol negotiated a deal with Seattle to cooperate on research into predicting gun violence. That collaboration was announced in May of 2013.

Following a favorable review of PredPol's pitch by Suhr, over the summer of 2012 PredPol negotiated access to SFPD's historic crime data and built PredPol's demonstration project for Mission Station, which mapped out locations where crime was most likely to occur based on historical crime data. Screenshots obtained from PredPol's internal server indicate the demonstration project was expanded to include all 10 of the city's patrol districts. However, Merritt says PredPol has yet to be used by patrol officers in the field.

From fall 2012 through spring 2013, Fowler repeatedly pressed Merritt for a set date for PredPol to be officially launched in San Francisco. Frustrated by SFPD's caution, and the department's more pressing goal of building its crime database warehouse, Fowler on May 9 lobbied Police Commissioner Loftus and Tony Winnicker, a senior advisor to Mayor Ed Lee.

Four days later, Merritt wrote to Suhr that the SFPD was not prepared to go public with PredPol: "Chief, I corresponded with PredPol and suggested that we not participate in this announcement at this time. ... While we will be rolling out PredPol and the gun violence module, I would like to wait until we are fully implemented before any announcements."

While the SFPD continues to weigh the merits of PredPol, more than 150 police departments nationally are deploying predictive policing analytics. Many departments are developing their own open-source algorithms, and a few tech heavyweights like IBM and Palantir are getting in on the game. But PredPol has emerged early to dominate the market. The company has sold its proprietary software here and abroad, from Kent County in England to Seattle, Wash., and here in the Bay Area to cities including Richmond, Los Gatos, Morgan Hill, and Santa Cruz. The origins of predictive policing, and of PredPol, however, are in Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, and Iraq.

The concept of predictive policing — forecasting where crimes are more likely to occur and attempting to prevent them — is rooted in the thinking of George Kelling, a theorist with the conservative Manhattan Institute. Kelling's ideas, published in several papers in the 1980s, centered around ways to better deploy limited police resources by using statistical analysis. The New York City Police Department's development and introduction of CompStat in the mid-1990s reorganized policing in the city to respond to trends in crime statistics, and to allocate officers accordingly. CompStat was a major change in American law enforcement. Police commanders increasingly made decisions based on data and statistical analysis rather than hunches. Crime rates dropped in New York following CompStat's introduction — although there is no consensus that CompStat was responsible. Nevertheless, the program became the gold standard for every police chief.

Virtually every police department in medium to large cities today has one or more crime analysts on staff to crunch numbers and plot past crimes on maps. Few had ever tried predicting future crimes though. Interest in predictive policing spiked nationally in 2009 as the National Institute of Justice, the research and policy branch of the Department of Justice, published a series of white papers and doled out millions in grant money to seven police departments to undertake the task.

One of the grants went to the Los Angeles Police Department in 2009. When LAPD applied for the grant two years earlier, it was still under the leadership of Bill Bratton, who had championed CompStat's introduction while serving as NYPD commissioner from 1994 to 1996. Bratton wanted LAPD to be a crime-fighting laboratory. He assigned then-Lt. Sean Malinowski, a former Fulbright scholar who had studied counterterrorism at the Egyptian National Police Academy in Cairo, to be the lead investigator on LAPD's predictive policing grant.

Around the same time, researchers at the Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics at the University of California, Los Angeles were using grants from the Army, Air Force, and Navy to develop a series of algorithms based on earthquake prediction to forecast battlefield casualties and insurgent activities in overseas war zones. Army Research Office documents reveal that the work of anthropology professor Jeffery Brantingham, math professor Andrea Bertozzi, and math postdoc George Mohler was repurposed from its initial application of tracking insurgents and forecasting casualties in Iraq to analyze and predict urban crime patterns. This research would lead to the creation of PredPol.

The UCLA researchers eventually joined up with Malinowski and the LAPD to put their military-oriented research into practice in a domestic policing context. Foothill Division, a sprawling LAPD patrol sector in the northeast San Fernando Valley that, at 46 square miles, is about as big as San Francisco, was chosen as the site of a pilot program in 2012. Malinow -ski was partnered with Capt. Jorge Rodriguez, who worked every patrol division of the LAPD and on several task forces. During the predictive policing pilot program, Rodriguez says Foothill Division led all patrol divisions in crime reductions for every week of 2012.

"Every morning, we get a report from PredPol for which 20 boxes are going to be where crime is most likely to happen," says Rodriguez.

Maps are distributed to the three daily patrol shifts, and information about crime that happens on a particular day is included in the predictions that go to the next shift. Patrol officers are assigned to sit in computer-generated boxes produced by predictive policing software from geographic analyses of six years' worth of crime data.

"If your resources are diminished, then you want to focus on those boxes with the highest rate of crime," says Rodriguez.

Along with the printouts given to each patrol team, Foothill Division deploys four officers to patrol the areas where crime is occurring in clusters. This team either operates as a uniformed deployment or in plainclothes, depending on how they are being used on that particular day. Enforcement is not the only part of Foothill Division's predictive policing strategy — Rodriguez keeps a steady line of communication with his community liaison officers on what residents are telling the department about crime in areas highlighted by crime predictions. "There's something that's been sparking that trend in that particular area over the past six or seven years," Rodriguez explains. Speaking with residents, he says, gives police the context that pure statistics and computer modeling cannot provide.

After discontinuing its use of predictive policing methods at the beginning of 2013 to evaluate the program, LAPD restarted its use of predictive policing in March and expanded beyond Foothill to two other patrol divisions. The current focus is for burglaries of all categories and car theft, which are the most persistent problems in Foothill.

PredPol has played up its role in the LAPD's deployment of predictive policing methods in order to expand to other departments in the U.S. and abroad. Advertising "scientifically proven field results" on its website, PredPol says its technology was responsible for a 13 percent drop in crime over the first four months it was used by L.A. cops in the Foothill Division. The company claims the rest of the city experienced a 0.4 percent increase in crime over the same period.

But it isn't clear exactly whose software LAPD has been using. PredPol's name does not appear anywhere in L.A.'s predictive policing records, though LAPD personnel say they are using PredPol's software, and Malinowski's contact information has appeared in PredPol's sales literature distributed to other cities. In response to a public records request for contracts between L.A. and PredPol, the LAPD says no such agreements exist.

Regardless of whatever combination of programs LAPD is using, no one knows if predictive policing is even working in Los Angeles. Crime rates across the city have been dropping for a decade, but the predictive methods are so new, and used in so few jurisdictions, that there's not enough data to run a scientific analysis. No analyst independent of the police, or their contractors, has rigorously tested predictive policing.

In 2010, a few years into LAPD's experimentation with predictive policing and collaboration with the team at UCLA, George Mohler's post-doc ended. Mohler had been an instrumental member of Brantingham's lab, and on much of the Army and Air Force-funded research used to predict crime. He ended up with a position in the math and computer science department at the University of Santa Clara. It was in Silicon Valley that Mohler made contact with Ryan Coonerty, Caleb Baskin, and Zach Friend. Together, they turned the UCLA research into a start-up.

Friend at the time was working as a crime analyst and public relations officer for the Santa Cruz Police Department. Coonerty, the former mayor of Santa Cruz (his father, Neal, was also mayor, and is currently a county supervisor), and Baskin, a Santa Cruz attorney from a prominent local family, pounced on the idea of predictive policing as a potential business. They enlisted an influential friend, Donnie Fowler.

Fowler, a San Francisco resident originally from Columbia, S.C., is a staunch Democrat who worked in low-level positions in the Clinton White House, and briefly for the Federal Communications Commission. He worked on the campaigns of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Wesley Clark, John Kerry, and, most recently, Barack Obama. Fowler runs a lobbying group called Dogpatch Strategies, whose clients include Facebook and Stanford University. Fowler comes from a political family; his father, Donald Fowler, was national chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1995 to 1997.

Mohler pulled his former UCLA advisor Brantingham back into the mix, and together they incorporated PredPol in January 2012. The new company quickly raised $1.3 million from angel investors and recruited members of Silicon Valley's elite. One of PredPol's advisers is Andreas Wigand, the former chief scientist at Amazon, and head of the Social Data Lab at Stanford University. Another PredPol advisor is Harsh Patel, formerly of In-Q-Tel, the CIA's venture capital firm.

On June 4, 2012, Wigand hosted a dinner to "showcase PredPol" and raise funds, according to an article in Forbes magazine. In addition to Wigand, PredPol boasts of the support of the former chief information officer of Autodesk, a former vice president at Plantronics, and a former eBay vice president. Fowler claimed in an e-mail to SFPD's Merritt that retired Gen. Wesley Clark is an adviser.

Shortly after forming PredPol, Friend left the Santa Cruz Police Department and successfully ran for county supervisor in Santa Cruz. Ryan Coonerty announced his intent to join Friend on the Santa Cruz Board of Supervisors in July of this year. Friend, Coonerty, and Fowler have served as PredPol's main lobbyists, approaching dozens of cities in an unusual sales effort. The statisticians Brantingham and Mohler have been very active in the sales effort too, giving presentations across the U.S. and lending PredPol an air of scientific authority before police customers and the press.

And that's where PredPol has been most successful: in its marketing algorithms. The company did not respond to interview requests for this story, but hundreds of records from more than a dozen cities tell a story of a company aggressively trying to expand its business.

PredPol distributes news articles about predictive policing's supposed success in L.A. to dozens of other police departments, implying that the company's software has been purchased and deployed by the LAPD. PredPol gave the mayor and city council of Columbia, S.C. — Fowler's hometown — a "confidential" briefing packet assembled by PredPol's Brantingham. Inside were slides and graphs illustrating L.A.'s supposedly successful use of predictive policing to reduce crime. In one graph, Brantingham compared year-over-year crime rates for two six-month spans. His graph shows that in November 2011 with the "rollout" of PredPol in L.A., crime dropped significantly compared to the prior year. He concludes that "successful rollouts in Los Angeles and Santa Cruz, California have seen reductions in crime of 12 percent and 27 percent respectively." Columbia purchased PredPol's software earlier this year for $37,000.

Swayed by the same claims, the city of Alhambra, just northeast of Los Angeles, purchased PredPol's software in 2012 for $27,500. The contract between Alhambra and PredPol includes numerous obligations requiring Alhambra to carry out marketing and promotion on PredPol's behalf. Alhambra's police and public officials must "provide testimonials, as requested by PredPol," and "provide referrals and facilitate introductions to other agencies who can utilize the PredPol tool." And that's just for starters.

Under the terms of the contract, Alhambra must also "host visitors from other agencies regarding PredPol," and even "engage in joint/integrated marketing," which PredPol then spells out in a detailed list of obligations that includes joint press conferences, training materials, web marketing, trade shows, conferences, and speaking engagements.

PredPol has offered its software at a 50 percent discount to many cities in order to get them to agree to shill for the company. In Salinas, PredPol slashed its $50,000 a year price tag in half on the condition that Salinas' police department "contribute to requested case studies, to be developed by PredPol, for use in its marketing."

The same sort of "case studies," developed by PredPol, led to an Aug. 15, 2011, New York Times article in which officers in Santa Cruz were depicted as having prevented auto burglaries thanks to the map's little red boxes. PredPol supposedly led the cops to a specific parking garage where they arrested two suspects. The Times quoted PredPol's executives and Santa Cruz cops, all of them praising the effectiveness of the software.

Since then, dozens of articles in national newspapers and magazines and local media have restated the same claims, often recycling quotes and statistics drawn directly from press releases written by PredPol for police departments. In Seattle, where PredPol signed a three-year contract, the company once again cut its list price, in this case by 36 percent, for a $135,000 agreement that pressures city leaders to do marketing for the company.

But the Seattle Police Department's chief of information technology, Mark Knutson, appears to have recognized the impropriety of making these public relations agreements. He wrote to PredPol's Coonerty in November 2012, saying "I don't think we can make this sort of thing a contractual commitment." But while Knutson refused to sign an agreement obligating Seattle employees to promote PredPol, nothing precluded voluntarily participating in press events.

A flashy press conference featuring the mayor and chief of police was the result; local and national media covered the event and wrote favorable articles, including a feature on NPR's All Things Considered.

The thrust of all this media hype has been that PredPol's software works, and that it has demonstrably reduced crime in cities where it's used, and that cops have even apprehended burglars caught in the act thanks to PredPol's little red boxes.

But the case of Norcross, Ga., casts doubt on these claims. Norcross purchased PredPol's software last summer for $28,500, agreeing to "participate in media outreach with PredPol, including issuance of a press release or holding of a press conference to announce the deployment of PredPol," and even requiring Norcross to "reference the PredPol brand name, wherever possible." On Aug. 23, PredPol issued a press release claiming that, thanks to its software, Norcross police "made multiple arrests on the first day of usage — including catching a burglar in the act."

PredPol's Brantingham called it a "big first day." Press reports multiplied, using quotes attributed to Norcross' police.

SF Weekly contacted Norcross requesting any sort of objective analysis of PredPol's performance. Norcross' Chief of Police Warren Summers responded that there have been no reviews or analyses of PredPol's software conducted, adding that "the Norcross Police Department has not utilized PredPol for a sufficient period of time to fully analyze its effectiveness."

In fact, every city that SF Weekly contacted seeking independent analyses or reviews of PredPol's software has told us that no such thing exists. In response to a public records request, Alhambra sent a "retrospective analysis" showing an increased accuracy in predicting where crimes were more likely to happen using PredPol over another common method called hotspotting, or mapping reported crimes to identify locations where offenses have frequently occurred. The analysis concluded that "at the level of deployment in Alhambra, PredPol predicts 262 percent more crime correctly than hotspotting." This analysis, however, was carried out by PredPol.

Similarly, when SF Weekly requested an independent third-party analysis of PredPol's performance in Salinas, the city replied that no such verification has ever been carried out. Nor has an independent analysis been conducted in PredPol's hometown of Santa Cruz. Instead, Santa Cruz provided a "radar" report assembled by PredPol's Mohler, which according to the Santa Cruz police "can go back a maximum of 3 months to compare the accuracy/effectiveness of PredPol." In addition, the Santa Cruz police provided academic journal articles authored by PredPol's Mohler and Brantingham, both of whom have a financial stake in proving the method works.

Philip Stark, chair of the statistics department at UC Berkeley, reviewed these documents and evaluated the company's claims of reducing crime. "I'm less than convinced," he says. Stark has studied demographics, climate models, and even methods of earthquake prediction. He's also been an expert witness in lawsuits involving truth in advertising, behavioral targeting, credit risk models, and oil exploration. Stark was skeptical.

"Does using it lead to a decrease in the crime rate?" he says. "You would need to do a comparison of similar-sized cities, with similar conditions, similar trends in their crime rates, with one group of cities using predictive policing, and the others not. Then you'd compare them to each other."

"A comparison of the same jurisdiction to itself means nothing," he continues. "Crime fluctuates normally from year to year in the same city." This is, however, exactly what PredPol and the LAPD have done in claiming that predictive policing reduced crime in L.A. PredPol made the same claims in Santa Cruz, and recently in Richmond, comparing year-over-year crime rates within a single city.

"By just doing it once, last year to this year, that's like a coin toss," says Stark.

"I know the guys behind PredPol. They're pretty smart," says Jerry Ratcliffe, the chair of Temple University's department of criminology. Ratcliffe has collaborated on multiple crime prediction projects, including development of software similar to PredPol's for another company in Pennsylvania. He says, however, that predictive policing is "relatively new," and as a technology it's "not proven by a stretch."

According to Ratcliffe, predictive policing methods simply haven't been subjected to rigorous independent testing that would allow a vendor to claim its product reduced crime and caught offenders. "Testing these systems requires experimental conditions which are rarely conducted in policing and crime prevention, unfortunately." And even if PredPol or another predictive policing algorithm works, that's not enough. "A computer will never prevent crime," says Ratcliffe. "Computer outputs need to tell police where crime is likely to happen, but then police need to come up with a policy response."

Ed Schmidt, a criminologist and veteran police officer, believes in the concept of predictive policing, but he has serious reservations about PredPol's supposed effectiveness. Schmidt just completed a review of predictive policing efforts across 156 cities, and says there is little actual data that predictive policing works. Even if it does work, there's no guarantee that using it will actually reduce the overall rate of crime in a city.

"I look at this all with skepticism," says Schmidt. "Where are they coming from, how are they implementing it? Are they just displacing crime between divisions? Are they just displacing crime from one precinct to another? Mine goes down, yours go up?" If that's the case, says Schmidt, then PredPol's product isn't a tool to reduce crime so much as to shift it around, and cops have been doing that for decades already through both hotspotting and street patrols: When police suppress crime in one part of a city, it moves to other areas where police aren't hovering.

Schmidt also worries that flashy predictive policing software like PredPol's might only be having a public relations impact, that it's more about looking 21st century and tough on crime. "For the amount of money they're spending, it's going to generate great press and it makes everybody feel safer," says Schmidt. "The cops and city can then say, 'We've employed the state-of-the-art stuff.'"

"The context here," according to Schmidt, "is that everybody's budget is dropping. So you have to be an innovator. You have to show your city council that you can do more with less, and effectively battle crime."

Stark, meanwhile, criticized the academic publications of Brantingham and Mohler upon which PredPol claims to have based its software algorithms. Unlike many scientific journal articles that are only ever read by a few dozen Ph.D.s working in the same field, PredPol has sent Brantingham and Mohler's work to many police departments as scientific proof of their product. The Santa Cruz Police Department has copies of Mohler and Brantingham's article from the American Journal of Statistics on hand.

Stark calls this paper a "thought experiment." The paper claims that crimes occur in patterns similar to earthquake aftershocks, and that based on this the location of future crimes can be predicted. "Earthquake prediction algorithms don't work," says Stark.

"It's a vague analogy," he says. "It's an observation that sometimes there are crime sprees. There is a little bit of physics with earthquake aftershocks. There isn't in crime."

If PredPol's links to earthquake prediction are questionable, its connection to militarized studies of insurgents and civilian deaths is potentially even more troubling. PredPol's web site and the company's presentations and sales materials available online, and obtained from cities through public records requests, do not mention the software's military origins. Nevertheless, Brantingham is a key scholar in the U.S. military's network of academics, and his UCLA lab is supported by the Air Force and Army. This trend of militarizing the police by outfitting them with military-grade weapons — or in the case of PredPol, using military-funded research and technology to change the ways cities are patrolled — has come under intense scrutiny in recent years. Reformers on both the right and the left worry that police tools and tactics developed for overseas battlefields will strip away Constitutionally-protected rights.

As recently as Sept. 6, PredPol's Fowler again pressed Merritt and Suhr on the date for SFPD's PredPol deployment. Right now, SFPD has no contract with PredPol. Merritt tells SF Weekly that the department is concerned about launching the program prematurely. She maintains that the SFPD "did the analysis with PredPol," and that the company showed that its product works. She added the caveat, however, that PredPol's proofs to the city compared the software's predictions to random predictions. "A captain isn't just doing random patrols right now," Merritt says.

Merritt's biggest concern is that even if PredPol works in predicting where crimes will happen, translating that into actionable strategies is another problem altogether. "Talking to L.A. made me proceed with caution. ... In L.A. I heard that many officers were only patrolling the red boxes, not other areas," says Merritt. "People became too focused on the boxes, and they had to come up with a slogan, 'Think outside the box.'"

At least one city has ditched PredPol because it lacked the basic resources to make use of it. The farming city of Salinas signed a three-year contract with PredPol in July 2012 for $75,000. Despite a reported 50 percent increase in the accuracy of violent-crime predictions by PredPol over Salinas police's previous hotspot crime-mapping method, the Monterey County Herald reported on Aug. 1 that police were too busy responding to a high volume of calls for service to adequately patrol the boxes highlighted by PredPol as likely areas for gun violence. Salinas Police Chief Kelly McMillan told the Herald that Salinas was the first time PredPol's software had been used to predict violent crime instead of property offenses, and that the volume of calls for service meant that officers could only patrol the PredPol boxes for six minutes at a time. And because there has been no independent analysis of PredPol's software in Salinas, or anywhere, it's not clear that it was even working.

Salinas amended its contract with PredPol on Sept. 22 after paying $25,000 for one year of services, effectively ending the software's use there. However, Salinas will still allow PredPol to access its crime data and has agreed to still do joint public relations on behalf of the company.

Rodriguez of the LAPD's Foothill Division believes that one of the reasons why his command has had success with predictive policing is the resources they are able to devote to policing the locations forecast as likely areas for crime. "One of the problems I've seen with other cities is that they buy into this program and think that'll be all they have to do — they expect results for the cost they pay," says Rodriguez. "This is not the panacea. We're dealing with statistics, we're dealing with probability," he says. "It's a big wide net we cast out into the ocean, and there's going to be some seepage."

That is, of course, if PredPol's version of predictive policing isn't an illusion based on incomplete science and aggressive marketing. American law enforcement's growing fascination with data-reliant strategies for complex and intransigent crime problems, says Crockford of the Massachusetts ACLU, is a troubling trend.

"It seems like we're moving in the wrong direction in how we think about crime," says Crockford. "Instead of figuring out why people are robbing houses, we're para-miltitarizing our police, turning all of them into robocops who take directions from computers as to how they go about their day." Crockford believes that relying on for-profit companies to deliver effective crime-fighting solutions poses serious risks. "There's a danger in overlap of the private sector and public sector. Policing shouldn't be influenced by corporate interests that profit from Big Data and that have an obvious interest in promoting these new technologies."

By Darwin Bond-Graham and Ali Winston

Wednesday, Oct 30 2013

The day before Halloween in 2012, Donnie Fowler, a lobbyist from a little-known tech start-up called PredPol, e-mailed a confidential login and password to the San Francisco Police Department's chief information officer, Susan Merritt. The password allowed Merritt to log into an online mapping tool that, according to Fowler and his business partners, was already predicting where crimes are likely to happen across San Francisco.

Fowler was, if his company is to be believed, giving the SFPD the keys to the next generation of crime-fighting, a program that draws from the past to help police, presumably, change the future. PredPol was hoping San Francisco would be wooed by the sci-fi promise of its product. After all, the media certainly has been.

Every other news article and TV clip about PredPol to appear over the past year, from Al Jazeera to the Wall Street Journal, has showcased the company and its software as if it were straight out of Philip K. Dick's short story, "The Minority Report." An algorithm, the exact nature of which is a proprietary secret closely guarded by PredPol, processes the inputted data and spits out 500-by-500 square-foot boxes on a map of the city. In these boxes, according to PredPol, the risk of crimes like auto-theft or battery are more likely to occur. Police access the program through a web browser. Its display is similar to Google maps, and features allowing cops to toggle different crimes, and zoom in on particular blocks, are simple and intuitive. For more than a year, the SFPD has quietly handed over troves of crime data to PredPol and allowed the company to integrate this software with the city's new police information technology systems.

Thousands of tech start-ups are popping up in the Bay Area these days, so it should come as little surprise that a few are selling apps to the police. PredPol, short for "predictive policing," is riding this wave of techno-mania and capitalizing on the belief, especially here in San Francisco, that there's a killer app for everything, including crime-fighting. This is a shift for the SFPD, a department that finally issued e-mail addresses to all of its officers and equipped its precincts with Internet connections in 2011.

The SFPD has yet to sign a contract with PredPol, but the company has aggressively marketed its software throughout the United States and overseas, winning hundreds of thousands of dollars in contracts. The company is run by politically connected individuals with ties to local and national Democratic Party leadership. It is backed by powerful Silicon Valley investors, and while the company's executives say the software originates from earthquake research, it actually is derived more from Army research into insurgencies and battlefield casualties.

And it's got a marketing strategy that recalls a military conquest. PredPol has required police departments that sign on to refer the company to other law enforcement agencies, and to appear in flashy press conferences, endorsing the software as a crime-reducer — despite the fact that its effectiveness hasn't yet been proven.

While PredPol is promoting its software and ginning up reams of good press for itself, veteran cops and prominent academics are skeptical about this latest crime-fighting gadget. Some say predictive policing doesn't work. Some even say specifically that PredPol's algorithm doesn't accurately predict future crimes, and that it has no proven record of reducing crime rates. Yet, without a contract, without public notice, even without most members of the Police Commission — the civilian body that oversees SFPD — knowing, the SFPD and PredPol have prepared to launch the company's controversial crime prediction software. As PredPol engineer Omar Qazi told SFPD staff back in February in an e-mail, "we can literally start generating predictions for you tomorrow."

Others worry that gadget-obsessed police and their contractors will not just waste public dollars on snake-oil solutions, but that in the process they'll actually undermine public safety. Kade Crockford, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts' Technology for Liberty Project, warns against the trend towards data and statistical software as a panacea. "People are excited about technological solutions for vexing social problems," Crockford says. "This is technophilia that's taken over. People assume if computers are involved, then it's smarter, more efficient."

PredPol's first inroads into San Francisco came at the initiative of Police Commissioner Suzy Loftus, a former prosecutor and policy specialist with the San Francisco District Attorney and the California Attorney General's Office. On May 17, 2012, Loftus was introduced to PredPol CEO Caleb Baskin and lobbyist Fowler. Loftus says that she first heard of predictive policing while working at the California Department of Justice.

"As a Police Commissioner, one of my primary goals is to support the department in adopting technology as a tool to solve, as well as prevent, crime," Loftus says in an e-mail. "After hearing more about this technology, I thought that SFPD and the Chief [Greg Suhr] should learn about it and decide if they thought it would be a good fit for the department. I called the Chief and told him what I thought about the potential and gave Donnie [Fowler] Greg's e-mail."

The civilian San Francisco Police Commission does not usually get involved with awarding contracts. While Loftus' contact with PredPol is not prohibited by her position as police commissioner, it is outside the scope of her official duties. Neither commission President Thomas Mazzucco nor Commissioner Angela Chan were aware of SFPD's relationship with PredPol, or of Loftus' introduction of the firm to SFPD's higher-ups.

"Good to meet both of you today," Loftus wrote Baskin and Fowler. "I am fascinated by what is possible here. I called [C]hief Suhr about it and told him that I met with you guys and think that if he likes it, it could be great for [San Francisco]."

After listening to Loftus, Suhr put PredPol's Fowler in touch with SFPD's Chief Information Officer, Susan Merritt. Thus began a year and a half of negotiation between the SFPD and PredPol over implementing the crime forecasting technology in the city — first as a no-cost demonstration in the Mission District, and then on a city-wide basis.

From the beginning, the effectiveness of PredPol had been a sticking point in the negotiations.

SFPD's Merritt was skeptical. In a series of e-mails from July 2012 to August 2013, Fowler laid out the technical specifications for the software and the types of crimes PredPol claims to predict. "The crimes we predict are burglary [residential, commercial, auto], auto theft, theft, robbery, assault, battery, and drug crime," Fowler wrote on July 23, 2012. "This goes significantly beyond your current ... mapping tools," he added. Affixed to Fowler's e-mail signature was the claim that PredPol's predictions are "twice as accurate as those made by vet cops."

Fowler's e-mails also make it clear that PredPol viewed the SFPD as a major potential contract that would drum up more business. The price, Fowler wrote on July 23, was "$150,000 with a 50 percent discount for signing up as one of the 15-20 early showcase cities nationally and a commitment for collaboration over the next three years." These showcase cities included Salinas, Seattle, and Alhambra.

Merritt pressed Fowler about whether the program could handle violent crime. "Homicide is a priority in the department — and if it is not there it would just beg the question why not," she wrote. Fowler admitted at the time that PredPol wasn't predicting homicides and gun violence. Failing to rope SFPD into its 15-20 city pilot program last year, PredPol devised a new idea, based on the demand for a tool to predict violent crimes, to include San Francisco in a gun-violence pilot program with Atlanta and Detroit. That would have used the three cities as case studies in its nationwide marketing push. When Detroit backed out, and San Francisco stalled, PredPol negotiated a deal with Seattle to cooperate on research into predicting gun violence. That collaboration was announced in May of 2013.

Following a favorable review of PredPol's pitch by Suhr, over the summer of 2012 PredPol negotiated access to SFPD's historic crime data and built PredPol's demonstration project for Mission Station, which mapped out locations where crime was most likely to occur based on historical crime data. Screenshots obtained from PredPol's internal server indicate the demonstration project was expanded to include all 10 of the city's patrol districts. However, Merritt says PredPol has yet to be used by patrol officers in the field.

From fall 2012 through spring 2013, Fowler repeatedly pressed Merritt for a set date for PredPol to be officially launched in San Francisco. Frustrated by SFPD's caution, and the department's more pressing goal of building its crime database warehouse, Fowler on May 9 lobbied Police Commissioner Loftus and Tony Winnicker, a senior advisor to Mayor Ed Lee.

Four days later, Merritt wrote to Suhr that the SFPD was not prepared to go public with PredPol: "Chief, I corresponded with PredPol and suggested that we not participate in this announcement at this time. ... While we will be rolling out PredPol and the gun violence module, I would like to wait until we are fully implemented before any announcements."

While the SFPD continues to weigh the merits of PredPol, more than 150 police departments nationally are deploying predictive policing analytics. Many departments are developing their own open-source algorithms, and a few tech heavyweights like IBM and Palantir are getting in on the game. But PredPol has emerged early to dominate the market. The company has sold its proprietary software here and abroad, from Kent County in England to Seattle, Wash., and here in the Bay Area to cities including Richmond, Los Gatos, Morgan Hill, and Santa Cruz. The origins of predictive policing, and of PredPol, however, are in Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, and Iraq.

The concept of predictive policing — forecasting where crimes are more likely to occur and attempting to prevent them — is rooted in the thinking of George Kelling, a theorist with the conservative Manhattan Institute. Kelling's ideas, published in several papers in the 1980s, centered around ways to better deploy limited police resources by using statistical analysis. The New York City Police Department's development and introduction of CompStat in the mid-1990s reorganized policing in the city to respond to trends in crime statistics, and to allocate officers accordingly. CompStat was a major change in American law enforcement. Police commanders increasingly made decisions based on data and statistical analysis rather than hunches. Crime rates dropped in New York following CompStat's introduction — although there is no consensus that CompStat was responsible. Nevertheless, the program became the gold standard for every police chief.

Virtually every police department in medium to large cities today has one or more crime analysts on staff to crunch numbers and plot past crimes on maps. Few had ever tried predicting future crimes though. Interest in predictive policing spiked nationally in 2009 as the National Institute of Justice, the research and policy branch of the Department of Justice, published a series of white papers and doled out millions in grant money to seven police departments to undertake the task.

One of the grants went to the Los Angeles Police Department in 2009. When LAPD applied for the grant two years earlier, it was still under the leadership of Bill Bratton, who had championed CompStat's introduction while serving as NYPD commissioner from 1994 to 1996. Bratton wanted LAPD to be a crime-fighting laboratory. He assigned then-Lt. Sean Malinowski, a former Fulbright scholar who had studied counterterrorism at the Egyptian National Police Academy in Cairo, to be the lead investigator on LAPD's predictive policing grant.

Around the same time, researchers at the Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics at the University of California, Los Angeles were using grants from the Army, Air Force, and Navy to develop a series of algorithms based on earthquake prediction to forecast battlefield casualties and insurgent activities in overseas war zones. Army Research Office documents reveal that the work of anthropology professor Jeffery Brantingham, math professor Andrea Bertozzi, and math postdoc George Mohler was repurposed from its initial application of tracking insurgents and forecasting casualties in Iraq to analyze and predict urban crime patterns. This research would lead to the creation of PredPol.

The UCLA researchers eventually joined up with Malinowski and the LAPD to put their military-oriented research into practice in a domestic policing context. Foothill Division, a sprawling LAPD patrol sector in the northeast San Fernando Valley that, at 46 square miles, is about as big as San Francisco, was chosen as the site of a pilot program in 2012. Malinow -ski was partnered with Capt. Jorge Rodriguez, who worked every patrol division of the LAPD and on several task forces. During the predictive policing pilot program, Rodriguez says Foothill Division led all patrol divisions in crime reductions for every week of 2012.

"Every morning, we get a report from PredPol for which 20 boxes are going to be where crime is most likely to happen," says Rodriguez.

Maps are distributed to the three daily patrol shifts, and information about crime that happens on a particular day is included in the predictions that go to the next shift. Patrol officers are assigned to sit in computer-generated boxes produced by predictive policing software from geographic analyses of six years' worth of crime data.

"If your resources are diminished, then you want to focus on those boxes with the highest rate of crime," says Rodriguez.

Along with the printouts given to each patrol team, Foothill Division deploys four officers to patrol the areas where crime is occurring in clusters. This team either operates as a uniformed deployment or in plainclothes, depending on how they are being used on that particular day. Enforcement is not the only part of Foothill Division's predictive policing strategy — Rodriguez keeps a steady line of communication with his community liaison officers on what residents are telling the department about crime in areas highlighted by crime predictions. "There's something that's been sparking that trend in that particular area over the past six or seven years," Rodriguez explains. Speaking with residents, he says, gives police the context that pure statistics and computer modeling cannot provide.

After discontinuing its use of predictive policing methods at the beginning of 2013 to evaluate the program, LAPD restarted its use of predictive policing in March and expanded beyond Foothill to two other patrol divisions. The current focus is for burglaries of all categories and car theft, which are the most persistent problems in Foothill.

PredPol has played up its role in the LAPD's deployment of predictive policing methods in order to expand to other departments in the U.S. and abroad. Advertising "scientifically proven field results" on its website, PredPol says its technology was responsible for a 13 percent drop in crime over the first four months it was used by L.A. cops in the Foothill Division. The company claims the rest of the city experienced a 0.4 percent increase in crime over the same period.

But it isn't clear exactly whose software LAPD has been using. PredPol's name does not appear anywhere in L.A.'s predictive policing records, though LAPD personnel say they are using PredPol's software, and Malinowski's contact information has appeared in PredPol's sales literature distributed to other cities. In response to a public records request for contracts between L.A. and PredPol, the LAPD says no such agreements exist.

Regardless of whatever combination of programs LAPD is using, no one knows if predictive policing is even working in Los Angeles. Crime rates across the city have been dropping for a decade, but the predictive methods are so new, and used in so few jurisdictions, that there's not enough data to run a scientific analysis. No analyst independent of the police, or their contractors, has rigorously tested predictive policing.

In 2010, a few years into LAPD's experimentation with predictive policing and collaboration with the team at UCLA, George Mohler's post-doc ended. Mohler had been an instrumental member of Brantingham's lab, and on much of the Army and Air Force-funded research used to predict crime. He ended up with a position in the math and computer science department at the University of Santa Clara. It was in Silicon Valley that Mohler made contact with Ryan Coonerty, Caleb Baskin, and Zach Friend. Together, they turned the UCLA research into a start-up.

Friend at the time was working as a crime analyst and public relations officer for the Santa Cruz Police Department. Coonerty, the former mayor of Santa Cruz (his father, Neal, was also mayor, and is currently a county supervisor), and Baskin, a Santa Cruz attorney from a prominent local family, pounced on the idea of predictive policing as a potential business. They enlisted an influential friend, Donnie Fowler.

Fowler, a San Francisco resident originally from Columbia, S.C., is a staunch Democrat who worked in low-level positions in the Clinton White House, and briefly for the Federal Communications Commission. He worked on the campaigns of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Wesley Clark, John Kerry, and, most recently, Barack Obama. Fowler runs a lobbying group called Dogpatch Strategies, whose clients include Facebook and Stanford University. Fowler comes from a political family; his father, Donald Fowler, was national chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1995 to 1997.

Mohler pulled his former UCLA advisor Brantingham back into the mix, and together they incorporated PredPol in January 2012. The new company quickly raised $1.3 million from angel investors and recruited members of Silicon Valley's elite. One of PredPol's advisers is Andreas Wigand, the former chief scientist at Amazon, and head of the Social Data Lab at Stanford University. Another PredPol advisor is Harsh Patel, formerly of In-Q-Tel, the CIA's venture capital firm.

On June 4, 2012, Wigand hosted a dinner to "showcase PredPol" and raise funds, according to an article in Forbes magazine. In addition to Wigand, PredPol boasts of the support of the former chief information officer of Autodesk, a former vice president at Plantronics, and a former eBay vice president. Fowler claimed in an e-mail to SFPD's Merritt that retired Gen. Wesley Clark is an adviser.

Shortly after forming PredPol, Friend left the Santa Cruz Police Department and successfully ran for county supervisor in Santa Cruz. Ryan Coonerty announced his intent to join Friend on the Santa Cruz Board of Supervisors in July of this year. Friend, Coonerty, and Fowler have served as PredPol's main lobbyists, approaching dozens of cities in an unusual sales effort. The statisticians Brantingham and Mohler have been very active in the sales effort too, giving presentations across the U.S. and lending PredPol an air of scientific authority before police customers and the press.

And that's where PredPol has been most successful: in its marketing algorithms. The company did not respond to interview requests for this story, but hundreds of records from more than a dozen cities tell a story of a company aggressively trying to expand its business.

PredPol distributes news articles about predictive policing's supposed success in L.A. to dozens of other police departments, implying that the company's software has been purchased and deployed by the LAPD. PredPol gave the mayor and city council of Columbia, S.C. — Fowler's hometown — a "confidential" briefing packet assembled by PredPol's Brantingham. Inside were slides and graphs illustrating L.A.'s supposedly successful use of predictive policing to reduce crime. In one graph, Brantingham compared year-over-year crime rates for two six-month spans. His graph shows that in November 2011 with the "rollout" of PredPol in L.A., crime dropped significantly compared to the prior year. He concludes that "successful rollouts in Los Angeles and Santa Cruz, California have seen reductions in crime of 12 percent and 27 percent respectively." Columbia purchased PredPol's software earlier this year for $37,000.

Swayed by the same claims, the city of Alhambra, just northeast of Los Angeles, purchased PredPol's software in 2012 for $27,500. The contract between Alhambra and PredPol includes numerous obligations requiring Alhambra to carry out marketing and promotion on PredPol's behalf. Alhambra's police and public officials must "provide testimonials, as requested by PredPol," and "provide referrals and facilitate introductions to other agencies who can utilize the PredPol tool." And that's just for starters.

Under the terms of the contract, Alhambra must also "host visitors from other agencies regarding PredPol," and even "engage in joint/integrated marketing," which PredPol then spells out in a detailed list of obligations that includes joint press conferences, training materials, web marketing, trade shows, conferences, and speaking engagements.

PredPol has offered its software at a 50 percent discount to many cities in order to get them to agree to shill for the company. In Salinas, PredPol slashed its $50,000 a year price tag in half on the condition that Salinas' police department "contribute to requested case studies, to be developed by PredPol, for use in its marketing."

The same sort of "case studies," developed by PredPol, led to an Aug. 15, 2011, New York Times article in which officers in Santa Cruz were depicted as having prevented auto burglaries thanks to the map's little red boxes. PredPol supposedly led the cops to a specific parking garage where they arrested two suspects. The Times quoted PredPol's executives and Santa Cruz cops, all of them praising the effectiveness of the software.

Since then, dozens of articles in national newspapers and magazines and local media have restated the same claims, often recycling quotes and statistics drawn directly from press releases written by PredPol for police departments. In Seattle, where PredPol signed a three-year contract, the company once again cut its list price, in this case by 36 percent, for a $135,000 agreement that pressures city leaders to do marketing for the company.

But the Seattle Police Department's chief of information technology, Mark Knutson, appears to have recognized the impropriety of making these public relations agreements. He wrote to PredPol's Coonerty in November 2012, saying "I don't think we can make this sort of thing a contractual commitment." But while Knutson refused to sign an agreement obligating Seattle employees to promote PredPol, nothing precluded voluntarily participating in press events.

A flashy press conference featuring the mayor and chief of police was the result; local and national media covered the event and wrote favorable articles, including a feature on NPR's All Things Considered.

The thrust of all this media hype has been that PredPol's software works, and that it has demonstrably reduced crime in cities where it's used, and that cops have even apprehended burglars caught in the act thanks to PredPol's little red boxes.

But the case of Norcross, Ga., casts doubt on these claims. Norcross purchased PredPol's software last summer for $28,500, agreeing to "participate in media outreach with PredPol, including issuance of a press release or holding of a press conference to announce the deployment of PredPol," and even requiring Norcross to "reference the PredPol brand name, wherever possible." On Aug. 23, PredPol issued a press release claiming that, thanks to its software, Norcross police "made multiple arrests on the first day of usage — including catching a burglar in the act."

PredPol's Brantingham called it a "big first day." Press reports multiplied, using quotes attributed to Norcross' police.

SF Weekly contacted Norcross requesting any sort of objective analysis of PredPol's performance. Norcross' Chief of Police Warren Summers responded that there have been no reviews or analyses of PredPol's software conducted, adding that "the Norcross Police Department has not utilized PredPol for a sufficient period of time to fully analyze its effectiveness."

In fact, every city that SF Weekly contacted seeking independent analyses or reviews of PredPol's software has told us that no such thing exists. In response to a public records request, Alhambra sent a "retrospective analysis" showing an increased accuracy in predicting where crimes were more likely to happen using PredPol over another common method called hotspotting, or mapping reported crimes to identify locations where offenses have frequently occurred. The analysis concluded that "at the level of deployment in Alhambra, PredPol predicts 262 percent more crime correctly than hotspotting." This analysis, however, was carried out by PredPol.

Similarly, when SF Weekly requested an independent third-party analysis of PredPol's performance in Salinas, the city replied that no such verification has ever been carried out. Nor has an independent analysis been conducted in PredPol's hometown of Santa Cruz. Instead, Santa Cruz provided a "radar" report assembled by PredPol's Mohler, which according to the Santa Cruz police "can go back a maximum of 3 months to compare the accuracy/effectiveness of PredPol." In addition, the Santa Cruz police provided academic journal articles authored by PredPol's Mohler and Brantingham, both of whom have a financial stake in proving the method works.

Philip Stark, chair of the statistics department at UC Berkeley, reviewed these documents and evaluated the company's claims of reducing crime. "I'm less than convinced," he says. Stark has studied demographics, climate models, and even methods of earthquake prediction. He's also been an expert witness in lawsuits involving truth in advertising, behavioral targeting, credit risk models, and oil exploration. Stark was skeptical.

"Does using it lead to a decrease in the crime rate?" he says. "You would need to do a comparison of similar-sized cities, with similar conditions, similar trends in their crime rates, with one group of cities using predictive policing, and the others not. Then you'd compare them to each other."

"A comparison of the same jurisdiction to itself means nothing," he continues. "Crime fluctuates normally from year to year in the same city." This is, however, exactly what PredPol and the LAPD have done in claiming that predictive policing reduced crime in L.A. PredPol made the same claims in Santa Cruz, and recently in Richmond, comparing year-over-year crime rates within a single city.

"By just doing it once, last year to this year, that's like a coin toss," says Stark.

"I know the guys behind PredPol. They're pretty smart," says Jerry Ratcliffe, the chair of Temple University's department of criminology. Ratcliffe has collaborated on multiple crime prediction projects, including development of software similar to PredPol's for another company in Pennsylvania. He says, however, that predictive policing is "relatively new," and as a technology it's "not proven by a stretch."

According to Ratcliffe, predictive policing methods simply haven't been subjected to rigorous independent testing that would allow a vendor to claim its product reduced crime and caught offenders. "Testing these systems requires experimental conditions which are rarely conducted in policing and crime prevention, unfortunately." And even if PredPol or another predictive policing algorithm works, that's not enough. "A computer will never prevent crime," says Ratcliffe. "Computer outputs need to tell police where crime is likely to happen, but then police need to come up with a policy response."

Ed Schmidt, a criminologist and veteran police officer, believes in the concept of predictive policing, but he has serious reservations about PredPol's supposed effectiveness. Schmidt just completed a review of predictive policing efforts across 156 cities, and says there is little actual data that predictive policing works. Even if it does work, there's no guarantee that using it will actually reduce the overall rate of crime in a city.

"I look at this all with skepticism," says Schmidt. "Where are they coming from, how are they implementing it? Are they just displacing crime between divisions? Are they just displacing crime from one precinct to another? Mine goes down, yours go up?" If that's the case, says Schmidt, then PredPol's product isn't a tool to reduce crime so much as to shift it around, and cops have been doing that for decades already through both hotspotting and street patrols: When police suppress crime in one part of a city, it moves to other areas where police aren't hovering.

Schmidt also worries that flashy predictive policing software like PredPol's might only be having a public relations impact, that it's more about looking 21st century and tough on crime. "For the amount of money they're spending, it's going to generate great press and it makes everybody feel safer," says Schmidt. "The cops and city can then say, 'We've employed the state-of-the-art stuff.'"

"The context here," according to Schmidt, "is that everybody's budget is dropping. So you have to be an innovator. You have to show your city council that you can do more with less, and effectively battle crime."

Stark, meanwhile, criticized the academic publications of Brantingham and Mohler upon which PredPol claims to have based its software algorithms. Unlike many scientific journal articles that are only ever read by a few dozen Ph.D.s working in the same field, PredPol has sent Brantingham and Mohler's work to many police departments as scientific proof of their product. The Santa Cruz Police Department has copies of Mohler and Brantingham's article from the American Journal of Statistics on hand.

Stark calls this paper a "thought experiment." The paper claims that crimes occur in patterns similar to earthquake aftershocks, and that based on this the location of future crimes can be predicted. "Earthquake prediction algorithms don't work," says Stark.

"It's a vague analogy," he says. "It's an observation that sometimes there are crime sprees. There is a little bit of physics with earthquake aftershocks. There isn't in crime."

If PredPol's links to earthquake prediction are questionable, its connection to militarized studies of insurgents and civilian deaths is potentially even more troubling. PredPol's web site and the company's presentations and sales materials available online, and obtained from cities through public records requests, do not mention the software's military origins. Nevertheless, Brantingham is a key scholar in the U.S. military's network of academics, and his UCLA lab is supported by the Air Force and Army. This trend of militarizing the police by outfitting them with military-grade weapons — or in the case of PredPol, using military-funded research and technology to change the ways cities are patrolled — has come under intense scrutiny in recent years. Reformers on both the right and the left worry that police tools and tactics developed for overseas battlefields will strip away Constitutionally-protected rights.

As recently as Sept. 6, PredPol's Fowler again pressed Merritt and Suhr on the date for SFPD's PredPol deployment. Right now, SFPD has no contract with PredPol. Merritt tells SF Weekly that the department is concerned about launching the program prematurely. She maintains that the SFPD "did the analysis with PredPol," and that the company showed that its product works. She added the caveat, however, that PredPol's proofs to the city compared the software's predictions to random predictions. "A captain isn't just doing random patrols right now," Merritt says.

Merritt's biggest concern is that even if PredPol works in predicting where crimes will happen, translating that into actionable strategies is another problem altogether. "Talking to L.A. made me proceed with caution. ... In L.A. I heard that many officers were only patrolling the red boxes, not other areas," says Merritt. "People became too focused on the boxes, and they had to come up with a slogan, 'Think outside the box.'"

At least one city has ditched PredPol because it lacked the basic resources to make use of it. The farming city of Salinas signed a three-year contract with PredPol in July 2012 for $75,000. Despite a reported 50 percent increase in the accuracy of violent-crime predictions by PredPol over Salinas police's previous hotspot crime-mapping method, the Monterey County Herald reported on Aug. 1 that police were too busy responding to a high volume of calls for service to adequately patrol the boxes highlighted by PredPol as likely areas for gun violence. Salinas Police Chief Kelly McMillan told the Herald that Salinas was the first time PredPol's software had been used to predict violent crime instead of property offenses, and that the volume of calls for service meant that officers could only patrol the PredPol boxes for six minutes at a time. And because there has been no independent analysis of PredPol's software in Salinas, or anywhere, it's not clear that it was even working.

Salinas amended its contract with PredPol on Sept. 22 after paying $25,000 for one year of services, effectively ending the software's use there. However, Salinas will still allow PredPol to access its crime data and has agreed to still do joint public relations on behalf of the company.

Rodriguez of the LAPD's Foothill Division believes that one of the reasons why his command has had success with predictive policing is the resources they are able to devote to policing the locations forecast as likely areas for crime. "One of the problems I've seen with other cities is that they buy into this program and think that'll be all they have to do — they expect results for the cost they pay," says Rodriguez. "This is not the panacea. We're dealing with statistics, we're dealing with probability," he says. "It's a big wide net we cast out into the ocean, and there's going to be some seepage."