From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Hidden in Plain Sight: Media Workers for Social Change, Chapter 3

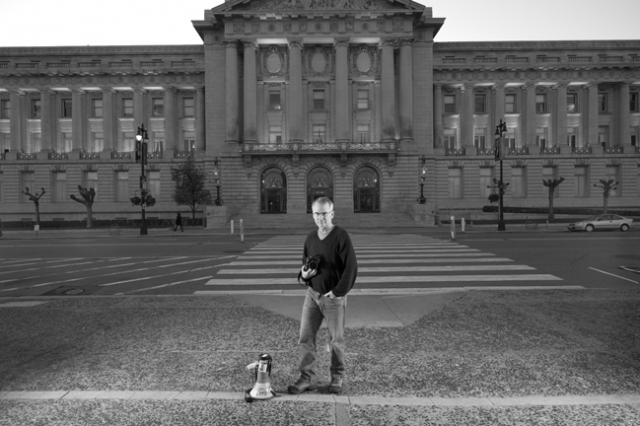

This is the third in a series of profiles of activist and alternative media workers in the Bay Area by Indybay contributor Peter M. Featured in this profile is Bill Hackwell, a photographer/activist who lives in Oakland. In the photo below, Hackwell stands in front of San Francisco's City Hall with the tools of his trade: a camera and a bullhorn.

In 1968 Bill Hackwell was in Viet Nam, assigned to Air Force intelligence as a photographer. His year there was the formation of what would be a life in photography and activism. “I had a political awakening there,” he said. “I consider myself an anti-imperialist and that’s where it began. I couldn’t express myself at the time, but I just … I felt lied to. All those things they told us that we were doing— it was the exact opposite.”

Hackwell came from a working-class New Hampshire town, where he had done poorly in high school, and his draft number was coming up, so he enlisted in the Air Force, thinking he would go to Germany. His father, uncles and grandfather had been in the military, and it felt natural to go. But he was the first in his unit to be sent to Viet Nam, and from that point on, things did not turn out the way he expected.

His assignment in Viet Nam was processing and reading aerial photographs. The Air Force was working with high-resolution cameras that he found to be interesting. He learned to make photo chemicals from scratch, and all about sensitometry and densitometry. His lab work was augmented with photo shoots.

“Because I was connected to intelligence,” he said, “I got the super-brainwash when I was in the military. They said, ‘We’re going over there to fight against the red menace. We’re bringing democracy to these people.’ The tone was also very racist. ‘These people can’t determine their own future, we have to bring it to them,’ we were told. ‘The meaning of life is different to them, they believe they’re coming back in another life.’ They just told us all this bullshit.”

He arrived in Viet Nam just after the Tet Offensive, when the U.S. was badly shaken by attacks all over South Viet Nam. Hackwell said opposition in the ranks was on the rise, and morale was plummeting. Tens of thousands fled the U.S. to escape the draft, tens of thousands were going AWOL, some were not carrying out orders, and others were sabotaging equipment.

Hackwell remembers his turning point. “I was on a helicopter pad on the flight line with another photographer, and we were looking east out over the rice paddies and mountains as the sun was coming up. It was beautiful, and we were going ‘Wow! Look at this!’ We were taking shots. The next thing we knew, we could see what they called the ranch hands, which were the defoliation planes that were trying to deprive the Viet Cong of cover. They were coming in and dropping the Agent Orange mist right over the rice paddies and all through the jungle. And it hit me right then. Here we were trying to destroy the country to ‘save’ it. And that started to ring in my head.”

A handful of soldiers in his unit, other photographers, felt the same as Hackwell. Pursuing a photographic vision helped Hackwell and these friends stay off of drugs and alcohol at a time when abuse was endemic. With their extra money, they bought cameras and lenses at the PX. They started neglecting their assignments—covering the war for the Air Force—to go out on their own and photograph the Vietnamese civilian struggle for survival in the middle of the war. “That in itself was exhilarating,” he said, “because suddenly I had an urgency about my photography. And looking back on it, I wish I’d done a lot more.”

He said the resistance of his group was passive-aggressive. But his commanding officer had his doubts. “He was someone of my age, or a little bit older, and the only difference was he had gone to college. And in his case, he was scared shitless of us as a group. Everyone has access to weapons and it can be a very volatile situation. It was kind of like there was a truce he had with us: ‘You don’t fuck with me, I don’t fuck with you, and we’ll all get out of here alive, okay?’”

In the end, Hackwell said, the war ended because of three factors: the cracks in the chain of command that he saw first-hand, the anti-war movement in the U.S., and the resistance of the Vietnamese people, who lost three million people and never gave up.

When he returned to the U.S., Hackwell overcame his feeling of failure as a high school student, and “begged” his way into college. He joined student anti-war organizing and gravitated towards Marxist professors. He spent a year documenting a village mired in poverty in Southern Italy. When he graduated in visual anthropology, in the top five percent of his class, there came an existential decision: to go to graduate school, and probably become a professor, or to pursue a career as an activist photojournalist. Clearly it was the latter that captivated him. “It’s the issue of praxis,” he said. “Unless you become an active participant your theories become separate from the reality. If you’re not involved in the struggle that you’re talking about, then you’re going to miss something, you’re not going to get it right.” He went to New York, where he began his career as an anti-imperialist, becoming involved in the struggles against the Shah of Iran, and for an end to U.S. support for apartheid South Africa.

Hackwell has been involved in a lot of issues, but his signature commitment has been to the Cuban Revolution. He went to Cuba to do labor as part of the Venceremos Brigade in the early 90s, then several times with Pastors for Peace, who were challenging the U.S. blockade by providing material aid to the Cuban people. In one campaign, another group Hackwell was involved in, Peace for Cuba was informed there was a shortage of pencils for school kids in Cuba. They did some research, found that the Blackfeet Indian Nation had a pencil factory, and bought up their seconds. They then supplied the Cubans with two million pencils.

Hackwell documented his activism in Cuba, and sent images to the Cuban media. He had opportunities to lecture in Cuba, and meet many Cuban photographers. Through these sorts of connections, he found himself able to put on several shows of his work on the socialist island.

The first, in 2002, was a one-man show at the Julio Mella Theater in Havana called “Struggles in the Belly of the Beast.” It was made up mostly of pictures of activists in the streets of North America. When Hackwell returned to the Bay Area from his opening, he told friends it was an “out of the body experience.” His show, he thought, gave Cuban viewers hope that there are North Americans who stand for social change, even if their politics are under the radar. Then, in 2006 Hackwell put was part of a show of a hundred prints between himself and a Cuban photographer, Jorge Valiente. It was called “Impressions of Brotherhood,” and was displayed in the Cuban National Library.

His third show in Cuba had its origins in political events between the U.S. government and Cuba. Five Cuban agents who came to the U.S. to monitor anti-Castro terrorist groups were arrested in 1998, basically on charges of conspiracy to commit espionage. When convicted in Florida they received extremely long sentences, from fifteen years up to double-life in prison. Hackwell became involved in the campaign to free the Five—as they are known—in 2001, and is in regular contact with them. While in prison, one of them, Antonio Guerrero, taught himself to paint, with some ability. Hackwell and Guerrero began to collaborate. Hackwell sent Guerrero photos of people involved in demonstrations to free the Five, and Guerrero then painted the faces of the protesters on canvas. “Bridge of Solidarity,” a show of their work, featured a series of these paintings, next to the photographs they were based on. It toured Cuba in 2008, going on display in every major city in the country. Hackwell does not exaggerate when he says his work is better known in Cuba than in the U.S.

Back in 1996, he had the opportunity to travel to Iraq with former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark. Clark was working on a book about the effects of sanctions on Iraq since the first gulf war, and Hackwell was brought along to make photographs to illustrate the text. At one point on their tour, they were at a technical high school in the city of Basra that had been blown up. The street was like many in Iraq, with standing water and garbage. When American bombs hit the sand, the shock waves broke up sewage pipes, and because of the sanctions, there were no spare parts to rebuild them. Garbage collection also went by the wayside. As Hackwell gazed at the scene, he noticed a young girl approach, curious about what he was doing. He started thinking “This is going to be a good photo if I can just unfreeze myself to take it.” He snapped with a 28mm lens, taking in the girl and the street behind her. A moment later children surrounded him, so he only took one frame. But he had gotten a shot that years later would almost seem to change the world.

Fast forward to October 2002. Bill had become an organizer for the ANSWER (Act Now to Stop War and End Racism) Coalition, which was planning a massive demonstration as the Bush administration prepared to launch the war against Iraq. They were printing thousands of posters, signs and buttons with the Iraqi girl’s picture. They had cropped the photo to the girl’s face, but it still projected dignity and hope in the midst of awful conditions. It was to be the most prominent image in what turned out to be a massive series of demonstrations.

Three days before that October demonstration, ANSWER got a call from BART, who wanted to know how many people were going to be marching. BART was being inundated with calls about their schedule during the event and had decided to add trains. That meant the demonstration was going to be much larger than they had anticipated. Hackwell said, “We just looked at each other and said ‘Oh shit!’ It was totally exhilarating.” Over 100,000 turned out.

Hackwell worked 24/7 throughout the run-up to the war. At his day job, where he evaluates drug abuse rehabilitation programs, he had a sympathetic manager, and he was able to take off for extended periods. ANSWER had gotten into the position of delivering the infrastructure for major demonstrations against the war on terror—the publicity, sound systems, stages, lead banners and security—by starting early. Others thought that immediately after 9/11 it would be too dicey to protest, but ANSWER jumped right in, and crowds came out. They got larger and larger—up to 200,000 in San Francisco on a single march—until the war started, and then things deflated. Hackwell gave it all he had, and said, looking back, “Movements never go away, but they go like waves, up and down. The activists don’t have control of a mass uprising; it’s just something that happens.”

He believes finding commonality is the essential ingredient of movements, and movements make history. This affects his photography. “When you’re taking photos of a demonstration you get in a mindset, kind of a zone,” he said, “where you know what you’re looking for, and you know that you have to rivet your attention to the activity. You have to be objective about what is going on. The only way the photo is going to be good is if you can say ‘I am recording this moment in history in the most interesting and compelling way possible.’ … People come together and become emboldened with the strength of numbers. That’s why photographing demonstrations is very exciting, and tends to produce indelible images.”

A couple of years ago ANSWER kicked off a project to organize active duty soldiers and veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan war, called March Forward. A video of one of their speakers calling it right to question and defy illegal orders has gone viral on the internet. Perhaps Hackwell hopes soldiers today will become aware of the contradiction in their situation, and as he did, will take a stand.

March Forward

http://www.billhackwell.com

Hackwell came from a working-class New Hampshire town, where he had done poorly in high school, and his draft number was coming up, so he enlisted in the Air Force, thinking he would go to Germany. His father, uncles and grandfather had been in the military, and it felt natural to go. But he was the first in his unit to be sent to Viet Nam, and from that point on, things did not turn out the way he expected.

His assignment in Viet Nam was processing and reading aerial photographs. The Air Force was working with high-resolution cameras that he found to be interesting. He learned to make photo chemicals from scratch, and all about sensitometry and densitometry. His lab work was augmented with photo shoots.

“Because I was connected to intelligence,” he said, “I got the super-brainwash when I was in the military. They said, ‘We’re going over there to fight against the red menace. We’re bringing democracy to these people.’ The tone was also very racist. ‘These people can’t determine their own future, we have to bring it to them,’ we were told. ‘The meaning of life is different to them, they believe they’re coming back in another life.’ They just told us all this bullshit.”

He arrived in Viet Nam just after the Tet Offensive, when the U.S. was badly shaken by attacks all over South Viet Nam. Hackwell said opposition in the ranks was on the rise, and morale was plummeting. Tens of thousands fled the U.S. to escape the draft, tens of thousands were going AWOL, some were not carrying out orders, and others were sabotaging equipment.

Hackwell remembers his turning point. “I was on a helicopter pad on the flight line with another photographer, and we were looking east out over the rice paddies and mountains as the sun was coming up. It was beautiful, and we were going ‘Wow! Look at this!’ We were taking shots. The next thing we knew, we could see what they called the ranch hands, which were the defoliation planes that were trying to deprive the Viet Cong of cover. They were coming in and dropping the Agent Orange mist right over the rice paddies and all through the jungle. And it hit me right then. Here we were trying to destroy the country to ‘save’ it. And that started to ring in my head.”

A handful of soldiers in his unit, other photographers, felt the same as Hackwell. Pursuing a photographic vision helped Hackwell and these friends stay off of drugs and alcohol at a time when abuse was endemic. With their extra money, they bought cameras and lenses at the PX. They started neglecting their assignments—covering the war for the Air Force—to go out on their own and photograph the Vietnamese civilian struggle for survival in the middle of the war. “That in itself was exhilarating,” he said, “because suddenly I had an urgency about my photography. And looking back on it, I wish I’d done a lot more.”

He said the resistance of his group was passive-aggressive. But his commanding officer had his doubts. “He was someone of my age, or a little bit older, and the only difference was he had gone to college. And in his case, he was scared shitless of us as a group. Everyone has access to weapons and it can be a very volatile situation. It was kind of like there was a truce he had with us: ‘You don’t fuck with me, I don’t fuck with you, and we’ll all get out of here alive, okay?’”

In the end, Hackwell said, the war ended because of three factors: the cracks in the chain of command that he saw first-hand, the anti-war movement in the U.S., and the resistance of the Vietnamese people, who lost three million people and never gave up.

When he returned to the U.S., Hackwell overcame his feeling of failure as a high school student, and “begged” his way into college. He joined student anti-war organizing and gravitated towards Marxist professors. He spent a year documenting a village mired in poverty in Southern Italy. When he graduated in visual anthropology, in the top five percent of his class, there came an existential decision: to go to graduate school, and probably become a professor, or to pursue a career as an activist photojournalist. Clearly it was the latter that captivated him. “It’s the issue of praxis,” he said. “Unless you become an active participant your theories become separate from the reality. If you’re not involved in the struggle that you’re talking about, then you’re going to miss something, you’re not going to get it right.” He went to New York, where he began his career as an anti-imperialist, becoming involved in the struggles against the Shah of Iran, and for an end to U.S. support for apartheid South Africa.

Hackwell has been involved in a lot of issues, but his signature commitment has been to the Cuban Revolution. He went to Cuba to do labor as part of the Venceremos Brigade in the early 90s, then several times with Pastors for Peace, who were challenging the U.S. blockade by providing material aid to the Cuban people. In one campaign, another group Hackwell was involved in, Peace for Cuba was informed there was a shortage of pencils for school kids in Cuba. They did some research, found that the Blackfeet Indian Nation had a pencil factory, and bought up their seconds. They then supplied the Cubans with two million pencils.

Hackwell documented his activism in Cuba, and sent images to the Cuban media. He had opportunities to lecture in Cuba, and meet many Cuban photographers. Through these sorts of connections, he found himself able to put on several shows of his work on the socialist island.

The first, in 2002, was a one-man show at the Julio Mella Theater in Havana called “Struggles in the Belly of the Beast.” It was made up mostly of pictures of activists in the streets of North America. When Hackwell returned to the Bay Area from his opening, he told friends it was an “out of the body experience.” His show, he thought, gave Cuban viewers hope that there are North Americans who stand for social change, even if their politics are under the radar. Then, in 2006 Hackwell put was part of a show of a hundred prints between himself and a Cuban photographer, Jorge Valiente. It was called “Impressions of Brotherhood,” and was displayed in the Cuban National Library.

His third show in Cuba had its origins in political events between the U.S. government and Cuba. Five Cuban agents who came to the U.S. to monitor anti-Castro terrorist groups were arrested in 1998, basically on charges of conspiracy to commit espionage. When convicted in Florida they received extremely long sentences, from fifteen years up to double-life in prison. Hackwell became involved in the campaign to free the Five—as they are known—in 2001, and is in regular contact with them. While in prison, one of them, Antonio Guerrero, taught himself to paint, with some ability. Hackwell and Guerrero began to collaborate. Hackwell sent Guerrero photos of people involved in demonstrations to free the Five, and Guerrero then painted the faces of the protesters on canvas. “Bridge of Solidarity,” a show of their work, featured a series of these paintings, next to the photographs they were based on. It toured Cuba in 2008, going on display in every major city in the country. Hackwell does not exaggerate when he says his work is better known in Cuba than in the U.S.

Back in 1996, he had the opportunity to travel to Iraq with former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark. Clark was working on a book about the effects of sanctions on Iraq since the first gulf war, and Hackwell was brought along to make photographs to illustrate the text. At one point on their tour, they were at a technical high school in the city of Basra that had been blown up. The street was like many in Iraq, with standing water and garbage. When American bombs hit the sand, the shock waves broke up sewage pipes, and because of the sanctions, there were no spare parts to rebuild them. Garbage collection also went by the wayside. As Hackwell gazed at the scene, he noticed a young girl approach, curious about what he was doing. He started thinking “This is going to be a good photo if I can just unfreeze myself to take it.” He snapped with a 28mm lens, taking in the girl and the street behind her. A moment later children surrounded him, so he only took one frame. But he had gotten a shot that years later would almost seem to change the world.

Fast forward to October 2002. Bill had become an organizer for the ANSWER (Act Now to Stop War and End Racism) Coalition, which was planning a massive demonstration as the Bush administration prepared to launch the war against Iraq. They were printing thousands of posters, signs and buttons with the Iraqi girl’s picture. They had cropped the photo to the girl’s face, but it still projected dignity and hope in the midst of awful conditions. It was to be the most prominent image in what turned out to be a massive series of demonstrations.

Three days before that October demonstration, ANSWER got a call from BART, who wanted to know how many people were going to be marching. BART was being inundated with calls about their schedule during the event and had decided to add trains. That meant the demonstration was going to be much larger than they had anticipated. Hackwell said, “We just looked at each other and said ‘Oh shit!’ It was totally exhilarating.” Over 100,000 turned out.

Hackwell worked 24/7 throughout the run-up to the war. At his day job, where he evaluates drug abuse rehabilitation programs, he had a sympathetic manager, and he was able to take off for extended periods. ANSWER had gotten into the position of delivering the infrastructure for major demonstrations against the war on terror—the publicity, sound systems, stages, lead banners and security—by starting early. Others thought that immediately after 9/11 it would be too dicey to protest, but ANSWER jumped right in, and crowds came out. They got larger and larger—up to 200,000 in San Francisco on a single march—until the war started, and then things deflated. Hackwell gave it all he had, and said, looking back, “Movements never go away, but they go like waves, up and down. The activists don’t have control of a mass uprising; it’s just something that happens.”

He believes finding commonality is the essential ingredient of movements, and movements make history. This affects his photography. “When you’re taking photos of a demonstration you get in a mindset, kind of a zone,” he said, “where you know what you’re looking for, and you know that you have to rivet your attention to the activity. You have to be objective about what is going on. The only way the photo is going to be good is if you can say ‘I am recording this moment in history in the most interesting and compelling way possible.’ … People come together and become emboldened with the strength of numbers. That’s why photographing demonstrations is very exciting, and tends to produce indelible images.”

A couple of years ago ANSWER kicked off a project to organize active duty soldiers and veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan war, called March Forward. A video of one of their speakers calling it right to question and defy illegal orders has gone viral on the internet. Perhaps Hackwell hopes soldiers today will become aware of the contradiction in their situation, and as he did, will take a stand.

March Forward

http://www.billhackwell.com

For more information:

http://www.streetdemos.net

Add Your Comments

Latest Comments

Listed below are the latest comments about this post.

These comments are submitted anonymously by website visitors.

TITLE

AUTHOR

DATE

If you're a Socialist Why not say so ?

Thu, Oct 14, 2010 3:20PM

We are 100% volunteer and depend on your participation to sustain our efforts!

Get Involved

If you'd like to help with maintaining or developing the website, contact us.

Publish

Publish your stories and upcoming events on Indybay.

Topics

More

Search Indybay's Archives

Advanced Search

►

▼

IMC Network